“The end of a novel, like the end of a children’s dinner-party, must be made up of sweetmeats and sugar-plums.”

Trollope does, ind eed, follow his own advice, filling the ending of this delightful social satire with all the “sweetmeats” any reader could desire. Between the introduction and conclusion are so many moments of wry humor, genuine thoughtfulness, and satisfying come-uppances that the extra sweetness at the end is actually a bonus. In this second of the Chronicles of Barsetshire, published in 1857, Trollope continues the story of Mr. Septimus Harding, the gentle and unambitious clergyman who, in The Warden (1855), resigned his appointment as warden of Hiram’s Hospital for the poor and became the vicar of a small church, living frugally above a chemist’s shop. His daughter Eleanor, who married reformer John Bolt at the end of The Warden, is now a widow with a small son–and considerable inheritance.

eed, follow his own advice, filling the ending of this delightful social satire with all the “sweetmeats” any reader could desire. Between the introduction and conclusion are so many moments of wry humor, genuine thoughtfulness, and satisfying come-uppances that the extra sweetness at the end is actually a bonus. In this second of the Chronicles of Barsetshire, published in 1857, Trollope continues the story of Mr. Septimus Harding, the gentle and unambitious clergyman who, in The Warden (1855), resigned his appointment as warden of Hiram’s Hospital for the poor and became the vicar of a small church, living frugally above a chemist’s shop. His daughter Eleanor, who married reformer John Bolt at the end of The Warden, is now a widow with a small son–and considerable inheritance.

Ecclesiastical controversies, many of them linked to the desire for power within the small world of the church hierarchy, still exist in Barchester, and the arrival of Mr. Slope, as chaplain to Bishop Proudie, signals fireworks. Slope, one of Trollope’s most unforgettable characters, is one of the slimiest, most sycophantic, and manipulative clergyman ever to appear in English literature, and before long, he is controlling the bishop, clashing with the bishop’s wife (who regards herself as co-bishop), using the unfilled wardenship of the hospital as a bargaining tool with Mr. Harding and Eleanor, alienating and even outfoxing Archdeacon Grantly, and seeking a wife with a large fortune.

Far more complex than The Warden, the novel has more fully developed characters acting from more realistic motivations. Victorian England, as we see it here, is a multileveled society which does not allow for much upward mobility, and the entrenched clergy regards itself as second only to the aristocracy. The human foibles, the back-biting, the selfishness, and the one-upsmanship which Trollope includes in his depiction of all levels of society are particularly ironic in the case of the godly churchmen, and the honest and straightforward Mr. Harding is a counterweight to them throughout the novel.

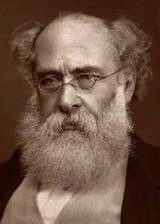

Several courtships and marriages are presented so unromantically here that it is difficult even to imagine the concept of sexuality, but the novel is witty and clever, and Trollope shows his continued development as a satirist. Not a writer of “sensation,” like Wilkie Collins, or of social criticism, like Dickens, Trollope has his own quiet style, and his wry observations about his world may resonate with the present reader more than either of those other giants.

Also reviewed here: Six other novels by Trollope. Just click on the Authors tab at the top of the Home page, if you are interested.