“Oil is a commodity, right, but it is the future of humanity, it will change the lives of millions. Millions of people, sir. It will change the face of the planet. It will flow like the milk and honey we are told of in the Good Book, a blessing to the children of earth. Now I ask you, what is [an ancient archaeological site] compared to that?”

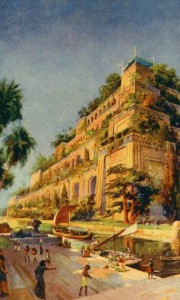

The land of Meso potamia, in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley, once boasted the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, among the Seven Wonders of the World. Highly developed ancient civilizations competed for power there four thousand years before Christ, leaving behind sites of immense archaeological importance as they defeated each other and formed new civilizations. In the modern era, Mesopotamia, now known as Iraq, fell under a succession of foreign rulers, and by 1914, when this novel opens, it was ruled from Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire, which was considered “the sick man of Europe” and ripe for overthrow. Iraq, a vast land of immense natural resources, is there for the picking–and it has no government of its own to interfere with potential exploitation by colonial powers.

potamia, in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley, once boasted the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, among the Seven Wonders of the World. Highly developed ancient civilizations competed for power there four thousand years before Christ, leaving behind sites of immense archaeological importance as they defeated each other and formed new civilizations. In the modern era, Mesopotamia, now known as Iraq, fell under a succession of foreign rulers, and by 1914, when this novel opens, it was ruled from Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire, which was considered “the sick man of Europe” and ripe for overthrow. Iraq, a vast land of immense natural resources, is there for the picking–and it has no government of its own to interfere with potential exploitation by colonial powers.

Virtually every country in Europe is on site, vying for oil, “the genie [that] will be the harbinger of a golden age,” and working to open the country to other business pursuits. The Germans are building a railroad from Basra through Baghdad and on to Constantinople, and they have secured a lease that gives them permission to excavate for t wenty kilometers on each side of the track as the railroad goes “coincidentally” through what appear to be vast oil fields. An American from Standard Oil is there, the French are trying to gain a foothold so that the railroad will not take shipping business from them, and the Russians and the Austro-Hungarian Empire may help finance the railroad in exchange for a piece of the action. With World War I about to break out, the need for oil and chrome ore (to make armor-piercing weapons) is pressing, and European countries are looking to Iraq as a source of materiel.

wenty kilometers on each side of the track as the railroad goes “coincidentally” through what appear to be vast oil fields. An American from Standard Oil is there, the French are trying to gain a foothold so that the railroad will not take shipping business from them, and the Russians and the Austro-Hungarian Empire may help finance the railroad in exchange for a piece of the action. With World War I about to break out, the need for oil and chrome ore (to make armor-piercing weapons) is pressing, and European countries are looking to Iraq as a source of materiel.

Trying to ignore most of this turmoil is John Somerville, a thirty-five-year-old archaeologist who has been working for three years at Tell Erdek, an ancient site near Baghdad which has so far yielded little in terms of artifacts. A broken piece of ivory (which may be plunder from somewhere else), a flat stone (which may depict the guardian spirit of an Assyrian king), a reconstructed clay tablet in a language spoken by the Assyrians, and the beginning of a wall made of kiln-fired bricks (used only in buildings for royalty) are all that Somerville has to show for his three years of work. Unfortunately, his excavations are in the path of the German-built railroad, and he is running out of money.

Hanging Gardens of Babylon, painted by an unnamed artist

As Somerville negotiates the governmental morass in Constantinople, trying to protect his dig, he also deals with deceitful British entrepreneurs and government officials who promise one thing and do another. He is reminded that “The British Empire is the most supreme example the world has ever witnessed of cooperation among nations…[and] Britain’s survival as an imperial power is at stake.” Though no one tells Somerville, the British believe that in case of war, they may well be on the side of the Germans, and that they will be able to use the Baghdad railroad to transport men and materials. They are not going to interfere, even if it means the destruction of unique archaeological artifacts.

As Booker Prize winner Barry Unsworth explores conflicts, deceits, and betrayals on all levels, he creates memorable characters, both on the dig at Tell Erdek and in the wider world. The Turks grant leases willy-nilly, in exchange for fees. The European nations pretend to want one thing when they are actually planning something else entirely. Some highly placed individuals pretend to represent the country when they are actually representing their own business interests, and an American geologist is double-dealing on many levels. Love stories and affairs among those on the archaeological team reveal as much about deceit and betrayal on a small scale as does the behavior of financiers and governments on a grand scale. No one can trust anyone else.

The Baghdad Railway, built by the Germans

Unsworth creates a vibrant picture of a tumultuous time and place, endowing what might have been an exotic tale of archaeological discovery with a broader thematic scope. The action never flags as the points of view change from Somerville’s excavation, to life at the team’s headquarters, to the courtship of Jehan an informer for Somerville, to government officials and financiers. As artifacts reveal the fate of the ancient “palace” and its inhabitants, Somerville is able to identify the seventh century BC ruler (or his double—another possible deceit). Ultimately, the reader recognizes that the coming world war, its atrocities, and its destruction bear much in common with the vicious warfare of the Assyrian past.

Notes: The author’s photo appears on http://www.kwls.org

The painting of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon by an unnamed artist appears on http://hanginggardensofbabylon.org

The Baghdad railway, built by the Germans, is shown in this photo: http://fi.wikipedia.org