“The unbelievable that came true stayed with me, and I believed in the unbelievable, in the star that had followed me through life, and with its gleam constantly before my eyes I began to believe in it more and more…Now that I had been brought to my knees, I realized that my star was brighter than ever, that only now would I be able to see its true brightness, because my eyes had been weakened by everything I had lived through, weakened so that they could see more and know more.”–Ditie, near the end of his life.

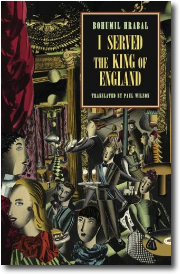

Czech author Bohumil Hrabal, often at odds with the government of Czechoslovakia during the 1970s and 1980s, first published this tragicomic novel as a typescript in 1979, and later in book form in 1983. Hrabal and fellow-members of the Jazz Section of the Czech Musicians’ Union distributed it secretly for two years before many were arrested and sentenced to jail for their efforts. Hardly what modern readers would consider subversive or dangerous, the novel is a first-person account by Ditie, who be gins his story as a teenage busboy at a rural hotel, progresses to waiter, and eventually to successful hotel owner. It gives nothing away (and the book cover itself includes this summary) to say that when the Czech government falls to communism, Ditie ends up working the roads in a mountain village.

gins his story as a teenage busboy at a rural hotel, progresses to waiter, and eventually to successful hotel owner. It gives nothing away (and the book cover itself includes this summary) to say that when the Czech government falls to communism, Ditie ends up working the roads in a mountain village.

The picaresque plot is the least important aspect of the book, since it is merely the framework for a series of often hilarious stories about the people he works with, the lives they have led, the values they maintain, their hopes for the future, and the sometimes large chasm between their dreams and reality. Set in rural hotels, at camps in the Czech mountains during the German occupation during World War II, and in Prague, where Ditie served, not the King of England, but the Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, the novel literally ends at the “end of the road,” where Ditie resides with his horse, goat, and cat. There, he lives on his memories, at peace with his fate—keeping the road to nowhere open for traffic, which never comes. Wanting to leave behind a record of his life, he spends his evening hours writing his autobiography, which becomes this book.

Ditie is a delightful story-teller, using the casual, almost innocent language of a young boy at the beginning and becoming philosophical and contemplative by the end. Hrabal’s sensitivity to small details and his accurate depiction of real people responding to real situations in sometimes odd and often darkly humorous ways make this sometimes satiric novel a delight to read.

Ditie is a delightful story-teller, using the casual, almost innocent language of a young boy at the beginning and becoming philosophical and contemplative by the end. Hrabal’s sensitivity to small details and his accurate depiction of real people responding to real situations in sometimes odd and often darkly humorous ways make this sometimes satiric novel a delight to read.

Ditie’s ribald and rowdy descriptions of his own sexual awakening and stories of how the customers at the various hotels cultivate female companionship give energy and humor to the beginning of the novel, but Ditie maintains his dignity when he describes the important people with whom he comes into contact—the highly esteemed headwaiter who “served the King of England,” but mentors him; the President of the Czechoslovakia during his stay at the hotel; and eventually Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia, for whom Ditie is personal waiter when he comes to the Hotel Tichota. The jealousies of his fellow-workers and their back-stabbing behavior sometimes force Ditie to seek new employment, but he is resilient, and he has the support of one of his earliest customers, who helps him to find new work when the times demand it.

The novel takes a new, darker turn, when Ditie, labeled a German sympathizer for his relationship with the German woman he later marries, leaves Prague to live in the mountains at a breeding station the Germans have established to develop a “refined race of humans.” Lise, his wife, becomes commander of the nursing corps and travels widely, while Ditie remains behind. When Lise returns from Warsaw with a small suitcase full of valuable stamps, confiscated from the Jews, they both know that their financial futures are secure.

takes a new, darker turn, when Ditie, labeled a German sympathizer for his relationship with the German woman he later marries, leaves Prague to live in the mountains at a breeding station the Germans have established to develop a “refined race of humans.” Lise, his wife, becomes commander of the nursing corps and travels widely, while Ditie remains behind. When Lise returns from Warsaw with a small suitcase full of valuable stamps, confiscated from the Jews, they both know that their financial futures are secure.

Eventually, Ditie must come face to face with his life, and he does so with a fatalism that is also full of grace. The reader may have a hard time believing that anyone could start so low, reach such heights, and then fall lower than he was at the beginning of his life–and still be grateful for the opportunity to learn from these experiences–but Ditie is relatively content. He has opened his mind, and he knows what is important, despite his harsh living conditions. All he wants is to leave behind a record. After all, he “served the Emperor of Ethiopia,” and that is important.

By turns hilarious and poignant, satiric and sensitive, the novel depicts many aspects of Czech society and culture, but it is, above all, the story of Ditie, in many ways an everyman. With symbolism throughout, and a repeating character, Zdenek, the headwaiter who “served the King of England,” who appears at every crossroads in Ditie’s life, the novel is more than a comic romp. A record of a time, place, and culture, it is also Ditie’s meditation on his life and his role, if any, in the wider world.

By turns hilarious and poignant, satiric and sensitive, the novel depicts many aspects of Czech society and culture, but it is, above all, the story of Ditie, in many ways an everyman. With symbolism throughout, and a repeating character, Zdenek, the headwaiter who “served the King of England,” who appears at every crossroads in Ditie’s life, the novel is more than a comic romp. A record of a time, place, and culture, it is also Ditie’s meditation on his life and his role, if any, in the wider world.

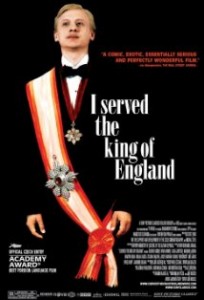

Released as a major film by Academy Award-winning Czech director Jiri Menzel, who also directed the film of Bohumil Hrabal’s Closely Watched Trains, this novel deserves to find a wide, long-overdue audience.

ALSO by Bohumil Hrabal: HARLEQUIN’S MILLIONS

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://opocno-city.opocno.cz

The photo for King Haile Selasse appears on http://harowo.com

The poster for the film version of this novel appears on http://www.imdb.com