“Who would he be in [his] new city? His experience would be of little use here. When the bus slowed in traffic, he had scanned ahead for an ambush, a useless precaution now. The sun was rising over the city. People were already amove, dashing across the expressways in their office clothes, hurdling over cement barriers and dashing to safety again. Women in bright overalls sprouted like fluorescent lichen along the highway sweeping dust into piles blown away by rushing traffic.” – comments by Chike.

In a novel of Nigeria which defies the usual stereotypes for that country, author Chibundu Onuzo tells a story of five individuals who form a surprising “family” in Lagos, and two others from the outside who affect the very lives of this group. Not a mystery filled with exotic scenes of violence, a polemic against the oil companies for despoiling the environment and profiteering, or a study of a police state so sadistic that the country was expelled from the Commonwealth of Nations in the 1990s, author Chibundu Onuzo’s offering introduces Nigeria as a place in which the people themselves feel familiar to the reader – at least at first. Two former soldiers, a wife escaping her abusive husband, a young rebel dreaming of a life as a radio star, and a teenage runaway who intends to fight if she is in danger, resemble those one might find in books from many other countries. As the action begins, however, the author, while still writing with a smile on her face, places her characters within the context of their lives in Lagos, Nigeria, considerably more challenging than the typical life of a young person in London or Paris, especially since these characters in Lagos are new to that complex and mysterious city.

In a novel of Nigeria which defies the usual stereotypes for that country, author Chibundu Onuzo tells a story of five individuals who form a surprising “family” in Lagos, and two others from the outside who affect the very lives of this group. Not a mystery filled with exotic scenes of violence, a polemic against the oil companies for despoiling the environment and profiteering, or a study of a police state so sadistic that the country was expelled from the Commonwealth of Nations in the 1990s, author Chibundu Onuzo’s offering introduces Nigeria as a place in which the people themselves feel familiar to the reader – at least at first. Two former soldiers, a wife escaping her abusive husband, a young rebel dreaming of a life as a radio star, and a teenage runaway who intends to fight if she is in danger, resemble those one might find in books from many other countries. As the action begins, however, the author, while still writing with a smile on her face, places her characters within the context of their lives in Lagos, Nigeria, considerably more challenging than the typical life of a young person in London or Paris, especially since these characters in Lagos are new to that complex and mysterious city.

Employing the use of local dialect, accents, and individual eccentricities, the author creates likable characters who are aware of human failings, often because they have been the victims of those failings, conditions which automatically evoke the reader’s sympathies. The two soldiers – Chike, an experienced officer, and Yemi, the lowest-ranked member of his platoon – have been fighting in the Delta against rebel militants and have been horrified by their superior’s wanton disregard for the rules of engagement, killing young people in villages on suspicion of crimes and burning down entire communities. Since participating in crimes against humanity is as bad as ordering those crimes, Chike and Yemi have only pretended to shoot, deciding to flee from the platoon at night to Yenagoa, heading for Lagos. Along the way they meet Fineboy, a hungry teenage militant who has been kidnapping oil workers in an effort to bring services to the poverty-stricken villagers who must work for the oil companies. Chasing him and anxious for vengeance against him is Isoken, a jeans-clad young girl from Lagos who had run into Fineboy the previous day when the group he was with found her and tried to rape her – her tight jeans being her only protection. These four, discovering they have a common enemy, decide to travel together to Lagos. Along the way, Oma, wealthy but married to an abusive husband, also joins them.

Employing the use of local dialect, accents, and individual eccentricities, the author creates likable characters who are aware of human failings, often because they have been the victims of those failings, conditions which automatically evoke the reader’s sympathies. The two soldiers – Chike, an experienced officer, and Yemi, the lowest-ranked member of his platoon – have been fighting in the Delta against rebel militants and have been horrified by their superior’s wanton disregard for the rules of engagement, killing young people in villages on suspicion of crimes and burning down entire communities. Since participating in crimes against humanity is as bad as ordering those crimes, Chike and Yemi have only pretended to shoot, deciding to flee from the platoon at night to Yenagoa, heading for Lagos. Along the way they meet Fineboy, a hungry teenage militant who has been kidnapping oil workers in an effort to bring services to the poverty-stricken villagers who must work for the oil companies. Chasing him and anxious for vengeance against him is Isoken, a jeans-clad young girl from Lagos who had run into Fineboy the previous day when the group he was with found her and tried to rape her – her tight jeans being her only protection. These four, discovering they have a common enemy, decide to travel together to Lagos. Along the way, Oma, wealthy but married to an abusive husband, also joins them.

Two other men also play major roles in the novel: Ahmed Bakare, son of a wealthy financier, has left a good job in England, where he went to school, and returned to Lagos, where he has founded a newspaper, the Nigerian Journal: “Nigerian news, by Nigerian people, for Nigerian people. Telling our own stories, creating our own narratives, emphasizing our truths.” Unfortunately the paper is dying. Reporters will not go where the news is, if the location sounds dangerous. Because the paper has repeatedly called for a revote on new President Hassan, who has apparently won the election by stuffing ballot boxes, no one will advertise in the paper. Readers are at risk if seen reading an editorial in a paper unpopular with the First Family. Ahmed, however, has decided he will “run the Journal into the ground before he gives in and lets it become popular reading in government circles.”

Sandayo decides he will not wait to be fired. He returns home to see his favourite (Yousuf) Grillo painting, an indigo long-necked woman, which reminds him of his wife.

The most “important” character is Chief Remi Sandayo, who has recently become the Honorable Minister of Education for the Federal Republic of Nigeria, a post of little interest to most citizens, and burdened with a small budget. “Education was of importance only when university staff went on strike, demanding higher pay for their worsening services.” Sandayo has found himself “at the head of a body paralyzed with bureaucracy…almost laughably so, his orders reaching their destination months after being issued, replies reaching him after a year.” His life is complicated by the rumor that he may be fired soon, just as his department is about to get ten million dollars for the Basic Education Fund.

For formal occasions, the men usually wear the agbada, with its layered sleeves and long lines, as seen with this father and son.

The five “escapees” have difficulty finding a place to stay in Lagos, since they have no connections and no money, and they end up living in a homeless encampment under a bridge, their past lives irrelevant in their housing emergency. Eventually, Fineboy discovers a hidden apartment in an abandoned building, a real residence in extraordinary condition and well furnished, though it has obviously not been used for years. With no fanfare, they all move in. A month later, however, someone enters the place late at night, accompanied by the “rasp of something heavy being dragged down the steps.” It is the owner of the house, carrying ten million dollars in a duffel bag – Minister Sandayo with his “budget.”

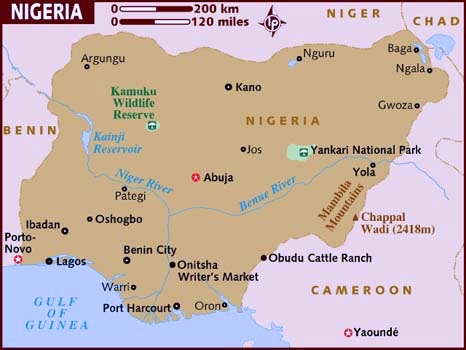

Map of Nigeria with Abuja in the center of the country and Lagos on the coast near the border with Benin. Click to enlarge.

What follows from this is sometimes akin to farce, as Sandayo cannot reveal himself publicly without instant arrest by the police, while the “family,” which wants to live good lives, also wants some of the money to live on. They cannot afford to break up as a group without endangering themselves, and they would like to return some of the money to the country as payment for the graft and financial abuses which they and others like them have paid for. No one is quite sure what to do with Sandayo, who cannot be released but who also cannot be allowed to “talk.” It is Bakare, the newspaper man, and a group of BBC reporters who become the biggest threats to the “family.” In a narrative tone much like that of the late nineteenth century novels of Charles Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Rudyard Kipling who let the action play out without interfering, Chibundu Ozuno creates a novel which lives and breathes on its own, while also generating excitement and complications guaranteed to keep a reader involved, despite the exotic setting and complex political ramifications.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://brittlepaper.com

The picture of busy Lagos is from https://www.economist.com

Sandayo decides he will not wait to be fired. He returns home to see his favourite (Yousuf) Grillo painting, an indigo long-necked woman, which reminds him of his wife. https://blog.jiji.ng/

For formal occasions, the men often wear the agbada, with its layered sleeves and long lines, as seen with this father and son. https://mamatrendy.wordpress.com

The map of Nigeria is from https://www.lonelyplanet.com