Note: Colum McCann was WINNER of the literary world’s most valuable prize, the IMPAC Dublin Award, for his previous novel, LET THE GREAT WORLD SPIN, which was also WINNER of the National Book Award.

“[Special Envoy George Mitchell] disliked his own importance in the [Irish peace] process. It was others who had brought the possibility here…He just wanted to land it. To take it down from where it was, aloft, like one of those great lumbering machines of the early part of the century, the crates of air and wood and wire they somehow flew across the water.”

Although Irish author Colum McCann has written six previous books and a collection of stories, winning many literary prizes including both the National Book Award and the IMPAC Dublin Prize for his most recent novel, Let The Great World Spin, he has never before written a novel set primarily in his native Ireland. Transatlantic shows that it has been worth the wait. Always precise and insightful in his descriptions, and so in tune with his settings that they seem to breathe with his characters, McCann uses three different plot lines set in three different time periods to begin this new novel, and all three plots are connected intimately to Ireland. In the process, he also creates a powerful sense of how men and women, no matter where they start out, may become so inspired to reach seemingly impossible goals that they willingly risk all, including their lives, to achieve success, often in new places, away from “home.” Always, however, they remain connected to their pasts. The unforgettable image at the top of this review – of US Envoy George Mitchell, in Belfast in April, 1998, aspiring to “land” the “great lumbering machine” of real peace between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland by somehow grasping it from aloft – is one which applies also to other characters in other times throughout this novel.

Although Irish author Colum McCann has written six previous books and a collection of stories, winning many literary prizes including both the National Book Award and the IMPAC Dublin Prize for his most recent novel, Let The Great World Spin, he has never before written a novel set primarily in his native Ireland. Transatlantic shows that it has been worth the wait. Always precise and insightful in his descriptions, and so in tune with his settings that they seem to breathe with his characters, McCann uses three different plot lines set in three different time periods to begin this new novel, and all three plots are connected intimately to Ireland. In the process, he also creates a powerful sense of how men and women, no matter where they start out, may become so inspired to reach seemingly impossible goals that they willingly risk all, including their lives, to achieve success, often in new places, away from “home.” Always, however, they remain connected to their pasts. The unforgettable image at the top of this review – of US Envoy George Mitchell, in Belfast in April, 1998, aspiring to “land” the “great lumbering machine” of real peace between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland by somehow grasping it from aloft – is one which applies also to other characters in other times throughout this novel.

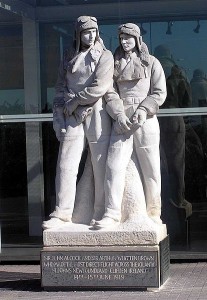

The imagery of flight which reappears throughout the novel comes from events which take place in Book One, set in 1919. John “Jack” Alcock and Arthur “Teddy” Brown, real characters, are readying themselves to compete in a contest to become the first individuals to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, non-stop, in less than seventy-two hours. Both men had served in the First World War, both had been shot down and imprisoned, and both wanted a clean slate, “the obliteration of memory.” Both love to fly the Vickers Vimy, and both know every aspect of its design. By making a few adjustments, “they [would be] using the bomber in a brand-new way: they were taking the war out of the plane, stripping the whole thing of its penchant for carnage,” and opening whole new worlds of possibility. Alcock and Brown hope to take off from Newfoundland and end somewhere in Ireland.

A local reporter, the fictional Emily Ehrlich, in her late forties, and her seventeen-year-old daughter Lottie, a photographer, ask the most perceptive questions of the pilots and get the biggest banners in the newspapers when the two aviators take off. Before they leave, Lottie persuades Brown to hand-carry a letter written by Emily to a family in Cork. (The Ehrlich family will eventually connect all the major plot lines throughout the book, and the letter will become a motif which develops further.) From the beginning of their trip in this open-cockpit plane, the reader becomes totally involved in the excitement and danger – how they try to stay warm with wires from the engine, what they eat, how they navigate at night by stars, and on foggy days with instruments – and luck. For Alcock and Brown, “The point of flight. To get rid of oneself. That was the reason enough to fly.”

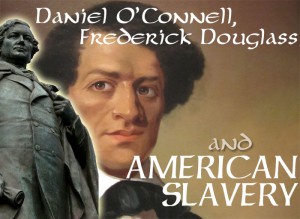

The second plot line reverts to 1845-46. Twenty-seven-year-old Frederick Douglass, a black slave from the United States, has arrived in Dublin to visit his Irish publisher, Richard Webb. Greeted by an assortment of Quakers, Methodists, and Presbyterians, he relates his experience on the ship, explains how he learned to read and write, and how he managed to escape his master, though he is technically still a slave. He is in Ireland because that is the land of Daniel O’Connell, the Great Liberator, and he hopes the Irish will “open themselves to him,” too. He hopes “to raise just a single hat, but eventually that hat would raise the heavens. He would go forth as a slave no more.” On his first trip through the countryside, however, he discovers how impoverished the local Irish are, with starving children, mothers begging to give away their infant children, the potato crop failing, famine beginning, while the Anglo-Irish landowners send most of their crops abroad for sale – and profit. Known as “the Black O’Connell, Douglass eventually meets with his idol, Daniel O’Connell. In Cork he also meets Lily, a maid, who becomes the progenitor of the Ehrlich family that will eventually report on the flight of Alcock and Brown in 1919, and continue throughout the later parts of the novel.

The third plot in Book One, during the two weeks leading to Easter, 1989, bring to life the almost insurmountable challenges of George Mitchell, former Senator from Maine and now Special Envoy to Northern Ireland, as he pushes, and pushes, and pushes to secure the peace between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland before Easter, his deadline. “He can see six, seven, eight sides to it all, even more,” but he will allow absolutely no more delays. He “just wanted to land it.” Despite the fact that we all know the outcome, McCann’s descriptive prose in this section is so intense and driven that it is impossible to stop reading. Mitchell elicits sympathy as he tries to keep everyone in line and focused on the end result. Everyone also has to save face.

The third plot in Book One, during the two weeks leading to Easter, 1989, bring to life the almost insurmountable challenges of George Mitchell, former Senator from Maine and now Special Envoy to Northern Ireland, as he pushes, and pushes, and pushes to secure the peace between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland before Easter, his deadline. “He can see six, seven, eight sides to it all, even more,” but he will allow absolutely no more delays. He “just wanted to land it.” Despite the fact that we all know the outcome, McCann’s descriptive prose in this section is so intense and driven that it is impossible to stop reading. Mitchell elicits sympathy as he tries to keep everyone in line and focused on the end result. Everyone also has to save face.

When George Mitchell went to Ireland for the Peace talks, his son was four months old. Ten years later, with Ireland at peace, Mitchell returned with his son.

Books Two and Three continue the lives of the Ehrlich characters introduced first in Book One – Lily, the maidservant, and her daughter, grand-daughter, great-granddaughter, and great-great grandson as they move back and forth across the Atlantic. All these fictional characters become involved in major and minor world events peopled here with real characters. Sometimes they attempt what seems impossible, and eventually they discover where “home” really is for each of them. As always, McCann’s descriptions give new life to sometimes ordinary events—“The poor were so thin and white, they were almost lunar,” “I sat at the table, and wiped my feet on moonlight on the floor,” “A wrapper of a chocolate bar sparred against the wind, and an empty wine bottle completed the romance.” Filled with insights and uniquely developed themes, this novel shows McCann at his most inspirational best. As he says at the beginning of Book Two:

…This is not the story of a life.

It is the story of lives, knit together,

overlapping in succession, rising

again from grave after grave. –Wendell Berry, “Rising”

ALSO by Colum McCann: LET THE GREAT WORLD SPIN DANCER THIRTEEN WAYS OF LOOKING

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.colgate.edu

The Vickers Vimy plane appears on http://flythebush.blogspot.com

The Alcock and Brown statue at Heathrow is found at http://en.wikipedia.org

The Douglass/O’Connell poster appears at http://class.georgiasouthern.edu

The photo of George Mitchell and his son are part of a story on the BBC: http://www.bbc.co.uk

ARC: Amazon Vine