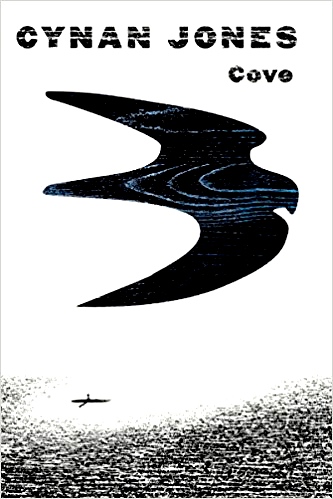

Note: Cove was WINNER of the Wales Book of the Year Fiction Prize, and a short story drawn from it, published in the New Yorker as ‘The Edge of the Shoal’, was WINNER the BBC National Short Story Award, 2017.

“The bay lay just a little way north. It was a short paddle from the flat beach inland of him, with the vacation trailers on the low fields above, but it felt private.

“His father long ago had told him that they were the only ones that knew about the bay, and that was a good thing between them to believe.”—narrator of the novella.

Cove, a novella by Welsh author Cynan Jones, so perfectly captures the mind and heart of its main character that many readers will read it in one sitting and then go back and reread all or most of it. An experimental novel in which the narrator’s individual thoughts are set off in separate paragraphs on wide-margined pages, the narrative hovers between a sharp, detailed, almost journalistic depiction of a speaker who goes out to sea in his kayak to scatter his father’s ashes, and some equally sharp, detailed pictures of what may be his hallucinations. All observations are the same for the speaker after a sudden storm and a lightning strike at sea leave him seriously injured, hungry, thirsty, and sometimes incoherent. Though he is well trained in the safety procedures which he recognizes may make the difference between his life and death at sea, he has gone out alone in his kayak, without informing the woman he loves, who is pregnant: He had hoped to spend this one last day with his father, in private.

Cove, a novella by Welsh author Cynan Jones, so perfectly captures the mind and heart of its main character that many readers will read it in one sitting and then go back and reread all or most of it. An experimental novel in which the narrator’s individual thoughts are set off in separate paragraphs on wide-margined pages, the narrative hovers between a sharp, detailed, almost journalistic depiction of a speaker who goes out to sea in his kayak to scatter his father’s ashes, and some equally sharp, detailed pictures of what may be his hallucinations. All observations are the same for the speaker after a sudden storm and a lightning strike at sea leave him seriously injured, hungry, thirsty, and sometimes incoherent. Though he is well trained in the safety procedures which he recognizes may make the difference between his life and death at sea, he has gone out alone in his kayak, without informing the woman he loves, who is pregnant: He had hoped to spend this one last day with his father, in private.

A preface begins the book, as a search crew, claiming to be looking for a missing child, approaches a pregnant woman on the beach. Half a page of white space later, someone finds what at first s/he thinks is a pigeon, with a wing torn off at the shoulder, only to decide, after seeing rings around its legs, that it is a peregrine falcon. The person retrieves the rings, which may be the peregrine’s ID numbers, from the bird’s legs. Shortly thereafter (represented by another half page of white space), a speaker sees “something you think is a wetsuit shoe, and the world tips, until you realize it’s a sneaker, colorful, like a tiny shelduck.” The rescue worker returns to his boat and uses the boat hook to pull something from the water, only to throw it back again. The crew heads back out to sea, leaving the speaker to realize that “they’ve missed something, there, at the edge of the tide….When you get to it, it is a doll.”

The peregrine falcon described here is said to have one red ring and one blue one on his legs, similar to these here, used for identification and history.

Reading this preface raises many questions, as the author uses first, second, and third person points of view here (and throughout the action), as if he is sending up flares regarding the drama to come. We do not know how much of the action in the Preface is real, though it feels so realistic and detailed that most readers will assume that all of it is real, nor to we know who is/are the speaker(s). Careful readers who like their novels tightly organized and chronological should not be discouraged by the uncertainties in this section, however. “Going with the flow,” trusting the author, allows him to share the confusion of the main character with his reader, while also creating a new and powerfully visceral experience as the actions of this main character proceed in chronological fashion. Some of the images in the preface repeat in the narrative which follows, suggesting that the preface is tied directly to that action and may be the follow-up to what happens later in the book, a flashforward perhaps. As the main action begins, the preface hides in the background as the reader becomes totally involved in the main character’s fight against nature after he has been hit by lightning.

The action of a single day begins in Part I with a devastating lightning strike on the narrator. “There is a basal roll. The sound of a great weight landing. A slow tearing in the sky….One repeated word now. No, no, no. When it hits him there is a bright white light.” Immediately, and without transition, the narrator looks toward the inland cliffs, hoping “the peregrine” might be there, followed by a seemingly irrelevant image in which he is paring away its feathers on the boat. He also catches a fish, and once again, the reader wonders about the character’s thinking and how seriously he may have been injured. He sees a razorbill. Only after all this does “he wake floating on his back, caught on a cleat by the elastic toggle of his wetsuit shoe. Around him hailstones melt and sink.” He now recognizes that he is “shell-shocked, trying to understand a layer of ash on the surface of the water…Dead fish lie around him.” Still, he manages, one-handed, to get back inside the kayak.

“It is hallucinatory, cartoonish, like a sea lion’s side-on in the water, a disk the size of a table.” –Ocean sunfish

The action continues. He sees a fin belonging to a huge sunfish, then finds a wren feather, a symbol of protection, inside his cell phone case with his dead phone. Gradually, the heat and the need for food and water begin to dominate his thoughts as he tries to avoid panic. At sundown, it becomes cold. Late at night, he hears a child’s cry, but he is so cold and overwhelmed that he begins to think, “I can go now. I’ve done my best.” Part II begins the next day, as he redoubles his efforts to return to land and “find a cove.” He thinks to himself that “If you disappear, you will grow into a myth for them. If you get back, you will exist as a legend.” His father’s voice offers advice as the narrator makes herculean new efforts to get back to land, using everything he can think of to help him.

The cry of a baby dolphin is mistaken by the narrator for a crying child, and he thinks of his own future child.

Jones ends the narrative at the perfect time. He has created a powerfully vivid story of a man trying to survive the elements, describing not only what he is thinking, but also what he remembers, what he is dreaming, and what he is hallucinating, making no distinctions among these processes: They are all part of his mental state – all part of his reality – and the narrator’s inability to distinguish among them matches similar difficulties the reader may have in determining what is real and what is imaginary. The narrator’s physical state and his deterioration, however, are shown chronologically and realistically here during his battle against the sea, and when the repeating images and symbols of the peregrine, feathers, the doll, and the wren appear, the reader cannot help but use them as a guide to interpreting the narrator’s mental health at that moment. Cynan Jones imbues a life or death struggle with a tension rare for such a short work. Though the style is experimental and takes some chances which may take a bit of getting used to, Jones is as aware of his reader as the narrator seems to be, providing clues throughout. Rereading the opening, or better yet, the whole novella, may tie together some aspects of the book missed the first time around, making this a memorable, not-to-be missed reading experience – high on my favorites list for the year.

ALSO by Jones: STILLICIDE

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.ft.com/

The peregrine falcon described here is said to have one red ring and one blue one on his legs, similar to these here, used for identification and history. A speaker removed both of them from the dead animal so that they would not be lost: http://chesapeakeconservancy.org/ Photo by Peter Turcik.

The narrator also sees a razorbill, a bird that spends its entire life on the water and takes only one partner. https://www.allaboutbirds.org

The ocean sunfish which batters the side of the narrator’s boat for several hours averages 500 – 2000 pounds. https://commons.wikimedia.org/

The crying of a baby dolphin frightens the narrator, since he thinks it is the crying of a human baby. http://www.coralreefphotos.com/