“When people learn that my son has cerebral palsy, they look at him with a mixture of sympathy and pity. I look at him as if he were a totem: with devotion, reverence and a feeling of inferiority. They say that a child with cerebral palsy is better suited for living on the Moon, where there’s no gravity. My son, therefore, is a man of the future, ready for interplanetary travel…My son is Captain Kirk.”

In this loving, and even exhilarating, memoir of his son Tito’s life, Brazilian author Diogo Mainardi introduces the reader to Tito from the moment of his birth in Venice, a birth bungled beyond belief by the doctor who delivered him. Mainardi and his wife Anna had been living in Venice, and, under the spell of this magical city and, especially, of the beautiful Scuola Grande di San Marco, designed by Pietro Lombardo in 1489 and converted into a hospital in 1808, Mainardi wanted his son’s birth to be in this special building, which Ezra Pound celebrated in one of his cantos for its perfect beauty. As Mainardi and Anna make their way on foot through the piazza on their way to Lombardo’s Scuola Grande di San Marco for the birth, they pass Andrea del Verrochio’s statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni, thought by many to be the “most glorious equestrian statue in the world.” Mainardi, overcome at this moment, is “in the grip of the same stupid aestheticism as Ezra Pound…I could only associate the perfect art of Pietro Lombardo [and Andrea del Verrochio] with an equally perfect birth. Because [such] Good, would be incapable of creating Evil…[or] a bungled birth.”

In this loving, and even exhilarating, memoir of his son Tito’s life, Brazilian author Diogo Mainardi introduces the reader to Tito from the moment of his birth in Venice, a birth bungled beyond belief by the doctor who delivered him. Mainardi and his wife Anna had been living in Venice, and, under the spell of this magical city and, especially, of the beautiful Scuola Grande di San Marco, designed by Pietro Lombardo in 1489 and converted into a hospital in 1808, Mainardi wanted his son’s birth to be in this special building, which Ezra Pound celebrated in one of his cantos for its perfect beauty. As Mainardi and Anna make their way on foot through the piazza on their way to Lombardo’s Scuola Grande di San Marco for the birth, they pass Andrea del Verrochio’s statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni, thought by many to be the “most glorious equestrian statue in the world.” Mainardi, overcome at this moment, is “in the grip of the same stupid aestheticism as Ezra Pound…I could only associate the perfect art of Pietro Lombardo [and Andrea del Verrochio] with an equally perfect birth. Because [such] Good, would be incapable of creating Evil…[or] a bungled birth.”

John Ruskin, in The Stones of Venice, also confirmed this aesthetic for Mainardi: “The architecture of a place, according to [Ruskin], has the power to shape the destiny of its inhabitants,” and for Mainardi that meant choosing to have his son born behind the gorgeous façade of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, which Ruskin believed “exalted the ‘law of the Spirit,’ rejecting Pride of Science, Pride of State, and Pride of System.” Unfortunately, in this case, medical science failed, the publicly owned Venice Hospital failed, and the system itself, with its rules and procedures failed – repeatedly – during Tito’s birth. The physician who delivered Tito made egregious mistakes. Deprived of oxygen for a prolonged period of time, Tito, the innocent victim of blunders, would be forever affected by cerebral palsy, unable to move as most people do – spastic.

Canaletto's picture of Scuola Grande di San Marco. Directly below the equestrian statue on the far right are two people walking, whom Mainardi identifies as Anna and himself on the way to the hospital in middle distance. See notes at end. Double-click to enlarge.

With references to artists, poets, historians, and even Alfred Hitchcock, author Mainardi associates the cerebral palsy of his son, who was destined to take many, many falls while growing up, with other well known events from the past, especially, in one long example, with Hitchcock’s film Vertigo, when James Stewart finally climbs the bell tower and overcomes his fear of heights, saying “I made it.” Mainardi tells us that Tito, “step by step, is making it too…Tito is James Stewart. He falls and survives. To hell with Kim Novak [who falls and dies].” Drawing parallels also between his own life and the many films with Lou Abbott and Bud Costello – who, he says, “falls better” than anyone else, ever – Mainardi also traces the history of treatment for palsied children, and, in the case of the Nazis, their extermination. He concludes that “I am the Simon Weisenthal of cerebral palsy. Josef Mengele is dead. Tito is alive.”

The sublime equestrian statue which Mainardi and Anna pass on the way to the hospital. See Canaletto painting, on right side. “If Andrea del Verrocchio made the most glorious equestrian statue in the world, then I can say that I made the most glorious club-footed boy in the world,” Mainardi says.

From the first moment when he strokes his unresponsive son in the incubator after his birth and watches as, for the first time, Tito writhes and arches his back, Mainardi is totally dedicated to this little boy. Mainardi then decides that “I am the Claude Monet of cerebral palsy. Tito is my water lily. He has become my sole subject matter. I devote myself entirely to him, he is my one passion…I always find in him an unexpected color, an unexplored shadow.” Later he goes on to say, “I never worshipped God. I never worshipped Man. However, I began to worship Tito. I began to worship domestic life. My gospel is an electricity bill. My temple is a greengrocer’s shop. Tito is Everything.”

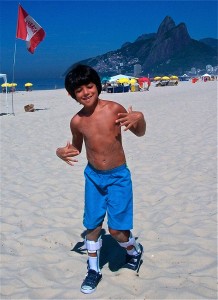

Ipanema Beach, Rio. Mainardi and his family move to Rio for nine years when he discovers that Tito can walk better on sand, since it is easier to fall on.

In other references, he notes that Comedian Francesca Martinez has cerebral palsy, and she refers to herself as a “wobbly” person, always about to fall. Christy Brown, author of My Left Foot, has parents who ignored all the prognoses, helping to create a writer respected around the world. A well-known singer has two sons with cerebral palsy, and his time spent with them in therapeutic programs is detailed here. Irish author Christopher Nolan, who could not speak or move at all, learned to type with a “unicorn stick” attached to his forehead, becoming an inspiration to Bono, who went to school with him and wrote the song “Miracle Drug” for him. How these people deal with their issues and celebrate their triumphs adds depth to the memoir and broadens its scope beyond the Mainardi family. And when the Mainardis have a second son, the opposite of Tito, in that Nico can do everything, the photos of the two boys together are both loving and lovely. Tito learns to walk with a walker and practices walking without aid, his father counting his steps till he falls, not stopping his counts till he reaches 424 steps here. Nico loves Tito and accepts him totally, and vice versa. The many family snapshots, with Tito grinning broadly in nearly every one, shows the reality of this family and its life behind closed doors, and no one who reads this memoir will doubt for a moment that every word of “worship” which the author expresses for Tito is absolutely true.

The real miracle of this memoir, to me, is that the author tells his story honestly, without a shred of easy sentimentality or “why-me-ism.” When he says that he worships Tito, it is easy to see that he really does, with all that that entails. He accepts reality and works his hardest to see that Tito’s reality becomes less challenging wherever possible, making Tito a real person for the reader and not just a cerebral palsy “victim.” It is clear that he is not a victim to Mainardi – just a boy, his son. He makes this memoir a story of himself and Tito, and he does not complicate this with asides in which he analyzes their relationship with Anna and Nico, though it is clear that those relationships are healthy and loving, also. For those of us whose children are blessedly “normal,” this memoir brings the behavior and the feelings of this parent out into the open as Mainardi lays bare his deepest thoughts about his child and his home and shows us that his family, too, is “normal,” a joy to know.

Photos, in order: The photo of Mainardi, Tito, and Nico, by Ruyn Teixeira, appears here: http://veja.abril.com.br/

The Canaletto painting of the Scuola Grande di San Marco is from http://www.abcgallery.com Mainardi says that the two faceless people “clinging to each other like Siamese twins” in front of the equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni, on the far right, represent him and Anna. “Ever since Tito’s Birth, on 30 September 2000, I have become a miniature man, without face or identity…What marks me out is fatherhood. I am merely a man eternally accompanying his wife to the birth of their son…I exist only because Tito exists.”

The equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni, by Andrea del Verrocchio, was finished by Alessandro Leopardi in 1488. It is considered the greatest equestrian statue in the world. Mainardi says: “If Andrea del Verrocchio made the most glorious equestrian statue in the world, then I can say that I made the most glorious club-footed boy in the world.” http://www.abcgallery.com

Enjoying Ipanema Beach in Rio, where the family lived for nine years, Tito learns to walk in the sand, where falls don’t hurt so much. From http://winkmag.com.br

A more mature Tito, at age twelve, is seen on http://pioneiro.clicrbs.com.br/

ARC: Other Press