Note: This book was WINNER of the Costa Award for Biography in 2011. It was also WINNER of the Ondaatje Prize.

“I know that my family were Jewish, of course, and I know they were staggeringly rich, but I really don’t want to get into the sepia saga business, writing up some elegiac Mitteleuropa narrative of loss…It could write itself, this kind of story. A few stitched-together wistful anecdotes…a bit of wandering around somewhere photogenic…some clippings from Google about ballrooms in the Belle Epoque. It would come out as nostalgic. And thin. I’m not entitled to nostalgia about that lost wealth and glamour…and I am not interested in thin.”—Prologue, Edmund De Waal, fifth generation of Ephrussis, here.

With this candid Prologue, author Edmund De Waal attempts to dispel any misgivings a reader might have about reading this book, which is the story of five generations of an impossibly wealthy family, their collection of art, their enormous houses, and especially their collection of over two hundred, antique Japanese netsuke, tiny sculptures which were originally used as fasteners for the purses that Japanese men wore around their waists. The book could easily have become the “sepia saga” the author has disdained in the Prologue. He offers even more caveats, too, emphasizing that this is not going to be a melancholy book, though the family lost virtually everything during World War II. “Melancholy,” he says, “is a sort of default vagueness, a get-out clause, a smothering lack of focus,” and he wants to convey, in discussing the collection of netsuke which he has inherited, that they are not only real and tactile, they are “small, tough explosion[s] of exactitude. [They] deserve this sort of exactitude in return.”

With this candid Prologue, author Edmund De Waal attempts to dispel any misgivings a reader might have about reading this book, which is the story of five generations of an impossibly wealthy family, their collection of art, their enormous houses, and especially their collection of over two hundred, antique Japanese netsuke, tiny sculptures which were originally used as fasteners for the purses that Japanese men wore around their waists. The book could easily have become the “sepia saga” the author has disdained in the Prologue. He offers even more caveats, too, emphasizing that this is not going to be a melancholy book, though the family lost virtually everything during World War II. “Melancholy,” he says, “is a sort of default vagueness, a get-out clause, a smothering lack of focus,” and he wants to convey, in discussing the collection of netsuke which he has inherited, that they are not only real and tactile, they are “small, tough explosion[s] of exactitude. [They] deserve this sort of exactitude in return.”

His decision to write this “exacting” book comes when he realizes “that I can either anecdotalise [the netsuke story] for the rest of my life…or go and find out what it means.” He has heard himself at dinner “entertaining” guests with the story, and he is embarrassed by his own behavior: “[The story] isn’t just getting smoother, it is getting thinner,” he observes. “I must sort it out now or it will disappear.” Giving up his work as a highly recognized, world-class potter for several months (which eventually grows to be almost two years of intermittent research), he determines to discover his family history and the history of his netsuke.

His decision to write this “exacting” book comes when he realizes “that I can either anecdotalise [the netsuke story] for the rest of my life…or go and find out what it means.” He has heard himself at dinner “entertaining” guests with the story, and he is embarrassed by his own behavior: “[The story] isn’t just getting smoother, it is getting thinner,” he observes. “I must sort it out now or it will disappear.” Giving up his work as a highly recognized, world-class potter for several months (which eventually grows to be almost two years of intermittent research), he determines to discover his family history and the history of his netsuke.

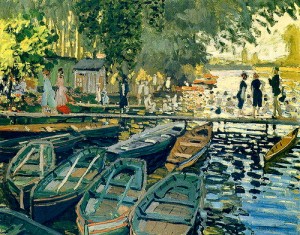

In Paris, he finds the family’s mansion on Rue Monceau, which in 1871 was lined with elaborate houses built by newly rich families. His family, the Ephrussis, had “owned” the grain market in Odessa, becoming one of the greatest grain exporters in the world, and their house is a grand one. He begins with the tale of twenty-one-year-old Charles Ephrussi, who arrives in Paris just as the house is being finished, then goes to Italy for a year of study, where he begins the first of his art collections and writes a “vanity book” about Albrecht Durer. Returning to Paris, where he has no interest in the family grain  business, he writes art commentary for the Gazette, which he eventually buys. The author does not hide the fact that Charles, as a character, does not much appeal to him at this stage – he thinks him “ridiculously affluent, very self-directed, and much, much too rich for his own good,” a feeling the reader shares. Charles is, however, active among artists and writers, including poet Jules Lafourgue; Proust, for whom he was a model for Swann; Renoir, who presents him in black coat and hat in the background of the “Luncheon of the Boating Party”; Monet who may also have used him in the same costume in the center of “Les Bains de la Grenouillere”; Degas, from whom he bought several paintings; and Manet, from whom he bought a painting of a bundle of asparagus. Eventually, he acquires forty major impressionist paintings displayed three deep on the walls of the newly built house. Always in the forefront, he is one of the first to absorb a new spirit sweeping the art world with the opening of Meiji Japan – “japonisme,” with its “air of eroticized possibility.” Eventually, he acquires thirty-three black lacquer boxes, an assortment of Japanese erotica kept in vitrines, and an incredible, two hundred sixty-four hand carved netsuke, which were already antiques when he bought them. These netsuke, the author emphasizes, “were the first things that have any connection to every day life.”

business, he writes art commentary for the Gazette, which he eventually buys. The author does not hide the fact that Charles, as a character, does not much appeal to him at this stage – he thinks him “ridiculously affluent, very self-directed, and much, much too rich for his own good,” a feeling the reader shares. Charles is, however, active among artists and writers, including poet Jules Lafourgue; Proust, for whom he was a model for Swann; Renoir, who presents him in black coat and hat in the background of the “Luncheon of the Boating Party”; Monet who may also have used him in the same costume in the center of “Les Bains de la Grenouillere”; Degas, from whom he bought several paintings; and Manet, from whom he bought a painting of a bundle of asparagus. Eventually, he acquires forty major impressionist paintings displayed three deep on the walls of the newly built house. Always in the forefront, he is one of the first to absorb a new spirit sweeping the art world with the opening of Meiji Japan – “japonisme,” with its “air of eroticized possibility.” Eventually, he acquires thirty-three black lacquer boxes, an assortment of Japanese erotica kept in vitrines, and an incredible, two hundred sixty-four hand carved netsuke, which were already antiques when he bought them. These netsuke, the author emphasizes, “were the first things that have any connection to every day life.”

The man in the back with the black top hat is identified as Charles Ephrussi.

By the 1880s, however, the new Jewish “aristocracy” in France, like Charles Ephrussi, are being blamed for the collapse of a large Catholic bank and a decline in the general economy. Though they are praised for their patronage of the arts, the Jews are loathed as upstarts. The Dreyfuss Affair from 1894 – 1906, further stokes the anti-Semitic fires in Paris, and Renoir, Cezanne, and Degas (the most virulent anti-Semite of them all), from whom Charles, an active patron, has bought many paintings, all distance themselves from him. Charles’s artistic tastes have also changed, and he is now collecting eighteenth century French paintings. When Viktor, Charles’s youngest cousin, gets married, Charles seizes the opportunity to ship the vitrine and its two hundred sixty-four netsuke to Vienna as his wedding gift.

Charles Ephrussi is also identified as the man in the center left, looking at the boats in this painting by Monet.

The Vienna house “makes the Paris house of the Ephrussi look demure,” the author notes, and Vienna is even more overtly anti-Semitic than Paris. The vitrine of netsuke is displayed in Viktor’s wife’s dressing room, and the family’s four children play with them as toys when they visit her room. The influx of hungry immigrants after the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, combines with the resentment of the Jews, and anti-Semitism increases even more. In 1922, the novel The City Without Jews, by Hugo Bettauer is already debating the “final solution” for the Jews, and as Hitler begins his rise to power, Viktor’s four children go in many different directions – to Mexico, England, and the US. None of the family treasures and none of the fortune survives the Anschluss. In 1946, Viktor’s son Iggie goes to Japan – with the netsuke. How he was able to acquire them from looted Austria, is another amazing story revealed here. He remains there for the rest of his life, then bequeaths the netsuke to the author. They remain in their vitrine in the author’s studio, the doors always unlocked so that the De Waal children can take them out, play with them, and even carry them in a pocket for luck, if they want to.

The Palais Ephrussi in Vienna is now the Vienna Casino.

Considering the esoteric subject matter, the hypnotic charm of this biography comes as a complete surprise. Though I had expected the book to be good, I had no idea how quickly and how thoroughly it would engage and ultimately captivate my interest. Through this sensitive author/artist, the reader shares the quest for information, delights in the discovery of new aspects of his family history, and thrills at his ability to connect not only with his ancestors but with the netsuke themselves. Ultimately, he connects, too, with the reader, who cannot help but feel privileged to have been a part of this author’s journey of discovery. My Favorite Non-fiction Book of 2012.

Note: A wonderful video interview with the author and a display of his netsuke show clearly the feelings which infuse the author’s search during this incredible book.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.bbc.co.uk, along with a fascinating interview.

The Ephrussi house in Paris: from http://was-stalin-a-rothschild.blogspot.com

The Hare with Amber Eyes and some of the other netsuke: from http://blogs.getty.edu

Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” with Charles Ephrussi identified in background in black top hat: from http://en.wikipedia.org

Monet’s “Les Bains de la Grenouillere” is a painting that Charles Ephrussi owned. Some have suggested that he is the black-dressed figure in the center left. From http://tokyojinja.com/ This site has some wonderful commentary on the Ephrussi family and its paintings.

The Palais Ephrussi, Vienna, designed by Theophil von Hansen now a casino: http://artandhockey.blogspot.com/