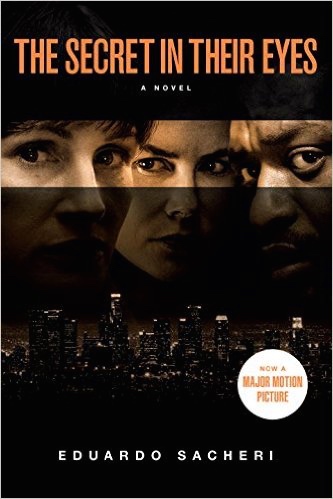

Note: The US film of this novel, starring Julia Roberts and Nicole Kidman, is scheduled for release on November 20, 2015. Other Press, which released this book in 2009, is re-releasing it on November 10, 2015.

“As workers in the criminal justice system [in 1974], we were too far removed from the things that were happening to know details, but sufficiently close to guess them. You didn’t have to be a fortune-teller. Every day, we saw people being arrested or heard news of other arrests. However, the people taken into custody were never put in jail, never brought before a judge, never remanded…”

Five years ago, the Spanish language film of this novel from Argentina won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film of 2010, and the subtitled version went on to become as big a success with film aficionados in the US as it had been with the Academy and Spanish-speaking audiences. Now a new film, in English, starring Julia Roberts and Nicole Kidman, is being released this month, and Other Press, which published the earlier novel on which the film is based, is reissuing it this month. Here, novelist Eduardo Sacheri’s extremely colloquial Spanish has been translated into equally colloquial English by John Cullen, and he has made his main characters so life-like that all differences in culture, background, and time frame disappear during the thirty-year time frame of the novel.

Five years ago, the Spanish language film of this novel from Argentina won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film of 2010, and the subtitled version went on to become as big a success with film aficionados in the US as it had been with the Academy and Spanish-speaking audiences. Now a new film, in English, starring Julia Roberts and Nicole Kidman, is being released this month, and Other Press, which published the earlier novel on which the film is based, is reissuing it this month. Here, novelist Eduardo Sacheri’s extremely colloquial Spanish has been translated into equally colloquial English by John Cullen, and he has made his main characters so life-like that all differences in culture, background, and time frame disappear during the thirty-year time frame of the novel.

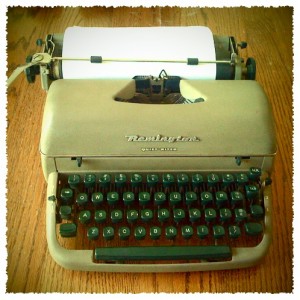

Main character Benjamin Chapparo, a deputy clerk and chief administrator associated with the investigative courts in Buenos Aires, has just recently retired, and, having “a lot of time, too much time, so much time that the daily trifles whose sum is my life quickly dissolve into the monotonous nothingness that surrounds me,” he decides to reconstruct his most challenging and emotionally memorable case from the late 1960s, bringing it and its participants up to the pre sent. Borrowing from the Justice Department the old, green Remington typewriter on which he has written all his case notes for the past thirty years (since he has never adjusted to the computer), he explains that “I decided to tell the story of Ricardo Morales. I made this decision because…it’s a story that needs no additions from me, and because, since it’s a story that needs no additions from me, and, because, since I know it’s true, I may dare to recount it all the way to the end.”

sent. Borrowing from the Justice Department the old, green Remington typewriter on which he has written all his case notes for the past thirty years (since he has never adjusted to the computer), he explains that “I decided to tell the story of Ricardo Morales. I made this decision because…it’s a story that needs no additions from me, and because, since it’s a story that needs no additions from me, and, because, since I know it’s true, I may dare to recount it all the way to the end.”

Alternating between the present and the terror of the late 1960s in Argentina, Chaparro lets the reader into his life, a life in which he bemoans his two divorces; his seeming inability to find true love; his commitment to justice at a time in which Argentina is experiencing violence from a succession of military dictators; and his thirty-year, unrequited love for a married colleague who seems not to know he adores her. On May 30, 1968, Chaparro is ordered to go to the scene of the murder and rape of Liliana Morales to oversee the work of the local police. There he discovers dozens of police milling around the murder scene and not doing anything they have not been told directly to do. Revealing his sensitivity to “sociology,” he remarks to the reader on the kinds of people with whom he works, and the types who gravitate to murder scenes. He describes them all, disgusted, with one word, beginning with A.

The old green Remington on which Chaparro has written his notes for thirty years.

When Romano, with whom he works (reluctantly), proceeds on his own to arrest two laborers who may have been working in an apartment near the victim’s, then beats them senseless to gain a confession, Chaparro investigates. And when he discovers the physical aftereffects of the beatings of the workers, and believes these men to be innocent, he reports Romano for abuse of power. Having attained a good relationship with the victim’s devastated husband, Chaparro hopes for an honest result in court.

The vagaries of the Argentinian judicial system, in which the judges and their clerks administer justice without a jury being involved, lead to Chaparro’s need to get crucial documents signed by judges and investigators who are not involved in the case and do not care, just to prevent the case from being shelved as unsolved. Later, Chaparro discovers the real murderer, but when he is arrested, he escapes justice. Ironically, it is Chaparro who is forced to escape for his life to the hinterlands, leaving behind everything that has had any meaning for him.

Palace of Justice, Buenos Aires.

Over the next thirty years, Chaparro works this case, off and on. His sympathy with the victim’s husband, who is devastated by the death of the only woman he has ever adored (a circumstance which Chaparro envies, because of his two divorces) never fades, though they lose contact for long periods of time. The conclusion provides some belief that “justice” can eventually result, regardless of the political confusions that have dominated many years of Argentina’s history. As the time frame alternates between present and past and within several different periods between the present and the time of the murder, the reader comes to sympathize with the honest citizens who yearn for peaceful lives at a time in which dictators and the military want only to protect themselves.

Juan Carlos Ongania, President of Argentina from 1966 – 1970, when the murder of Liliana Morales took place, was a military dictator who came to power in a coup.

Sacheri’s observations about his characters, their motivations, and the circumstances in which they find themselves by accident are particularly astute, giving sociological and psychological explanations for many of the unusual scenes in which they find themselves. His sensitive, often romantic, point of view regarding even minor characters makes them come alive for the reader, at the same time that characters with whom the reader already sympathizes will sometimes commit blunders affecting the outcomes of particular scenes. Chance plays a controlling role in many events, but at the same time, it frees the characters to follow their own instincts without worrying about responsibility for outcomes. The conclusion is full of surprises.

A first-class mystery, full of mysteries and revelations, set in a place with intrinsic interest for all readers, The Secret in Their Eyes is a winner as a novel, as well as a film.

The trailer follows:

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://leyendadeltiempo.wordpress.com

The old green Remington on which Chaparro has written his notes for thirty years is from http://michelle-bsktgirl.blogspot.com

The Palace of Justice in Buenos Aires appears here: http://www.igougo.com.

Juan Carlos Ongania, President of Argentina from 1966 – 1970, when the murder of Liliana Morales took place, was a military dictator who came to power in a coup. http://en.wikipedia.org