Note: Author Favel Parrett was WINNER of the Newcomer of the Year, Australian Book Industry Awards for 2012; WINNER of the Dobbie Award for 2012; and SHORTLISTED for the Miles Franklin Award for 2012.

“Out past the shallows, past the sandy-bottomed bays, comes the dark water – black and cold and roaring. Rolling out the invisible paths. The ancient paths to Bruny, or down south along the silent cliffs, the paths out deep to the bird islands that stand tall between nothing but water and sky. Wherever rock comes out of the deep water, wherever reef rises up, there is abalone. Black-lipped soft bodies protected by shell. Treasure.”

Dark, stark, and potent in its story and its message, Past the Shallows reduces life to its most basic elements as perceived by two young brothers, Miles and Harry Curren, who share the story of their uncertain lives on an island at the tail end of the inhabited world. Tasmania, off the south coast of Australia, where their father fishes for abalone in the dark water, offers no refuge, either physically or emotionally, from fate and the elements – just open water from there all the way to Antarctica. As difficult as the setting may be, the boys’ dysfunctional family is worse. The boys’ father, a threatening and often intemperate “hard man,” offers the young boys no emotional support in their difficult lives made worse by his drinking and irrational behavior. Their older brother Joe is living alone at his grandfather’s house, clearing it out after his death. Their mother died so long ago that they remember almost nothing of her or the car crash which killed her, just occasional flashes of memory of the ride they shared with her up to the fatal moment. The only woman with whom they have any contact is their Aunty Jean, whose own attitudes toward them alternate between callous indifference and the kind of attention that usually arises more from obligation than from love. There is no softness, no warmth of love, from anyone in their lives.

Dark, stark, and potent in its story and its message, Past the Shallows reduces life to its most basic elements as perceived by two young brothers, Miles and Harry Curren, who share the story of their uncertain lives on an island at the tail end of the inhabited world. Tasmania, off the south coast of Australia, where their father fishes for abalone in the dark water, offers no refuge, either physically or emotionally, from fate and the elements – just open water from there all the way to Antarctica. As difficult as the setting may be, the boys’ dysfunctional family is worse. The boys’ father, a threatening and often intemperate “hard man,” offers the young boys no emotional support in their difficult lives made worse by his drinking and irrational behavior. Their older brother Joe is living alone at his grandfather’s house, clearing it out after his death. Their mother died so long ago that they remember almost nothing of her or the car crash which killed her, just occasional flashes of memory of the ride they shared with her up to the fatal moment. The only woman with whom they have any contact is their Aunty Jean, whose own attitudes toward them alternate between callous indifference and the kind of attention that usually arises more from obligation than from love. There is no softness, no warmth of love, from anyone in their lives.

As the novel opens, the three brothers are on the beach at nearby Cloudy Bay on Bruny Island, a good place to surf, and their personal and emotional differences become clear from the outset. Nineteen-year-old Joe is marking time, getting ready to leave “home,” or what passes for it, and though he is accommodating to Harry when Harry is hungry, and also gives him some games to play on the beach so he won’t be bored while Joe and Miles are surfing, he is already planning a new life in a new part of the world. Miles, who appears to be about nine or ten, “could stay out in the water, forever, even if it was freezing,” and he “knew there were things that no one could teach you – things about the water. You just knew them or you didn’t and no one could tell you how to read it. How to feel it.” Harry, the youngest, perhaps six or seven, is different from his brothers. He hates the ocean, and fears it. Hyper-sensitive and observant of the nature around him, Harry is also vulnerable and a bit psychic, and when he picks up an abalone shell while waiting for his brothers to finish surfing, “every cell in his body stopped…[He] felt the people who had been here before, breathing and standing alive where he stood,” and even at his young age he “understood right down in his guts, that time ran on forever and that one day he would die.”

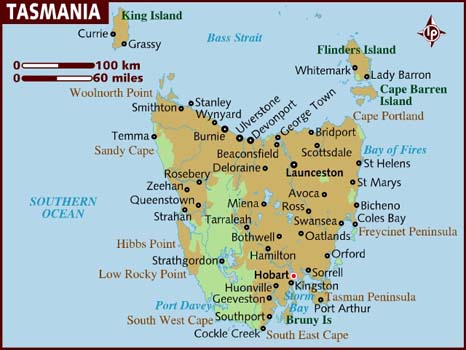

Double click to enlarge map. The action takes place at the far southern locations. Note Bruny Island, important here.

The narrative line hides itself within episodes told by both Miles and Harry, moving back and forth as they live their everyday lives and as they think about the past. A major event in their lives had occurred a few years ago, when their Uncle Nick was dragged by a rip current out to sea in the dark, and the usual search for him was postponed by another emergency which occurred that same night – the boys’ mother’s death in the car crash which the boys survived. Both Miles and Harry think about that night often, trying to make sense of their fading memories. The boys are close, though they lead very different lives.

During the summer, Miles must help his father on the boat in all kinds of weather, doing the job of an adult, while Harry, too young and too prone to seasickness to go on the boat at all, if he can help it, is able to take a little road trip with Aunty Jean to Hobart and the Regatta, a huge break in the routine he faces every day. Gradually, the story of Aunty Jean’s bad relationship with the boys’ father emerges, and the reader can only wonder why she made the choices she made which have so alienated the family. Though emergencies often occur at sea, Dad and his partner on the boat often act without thinking, thereby increasing the chances that emergencies will become disasters. When these do occur, the author provides just enough detail to make the reader feel for the characters as they fight against the harshness of nature and the accidents of fate, without any hearts and flowers or any sentimental embroidery of the facts.

The author keeps her writing clean, developing strong contrasts between life at sea and the life on land which Harry pursues. Life even becomes a bit sweet for him when he befriends a small dog and, eventually, its owner, an outcast, George Fuller, who lives alone, takes care of his house, does his own fishing at Cloudy Bay, and simply listens to Harry, the only person who does. As the author continues to show life in all its permutations, Parrett introduces characters from the community, showing how others in the area live their lives, some much more successfully than the people the boys come into contact with in their daily lives. Some people offer them advice about getting out of their home situation while there is still time, while others, like George, Harry’s friend, teach them how to fend for themselves more successfully. The father’s treatment of the fearful Harry on one trip out to sea leads ultimately to the novel’s climax.

“Cloudy Bay looked brand new. Just born, the outlines becoming sharp as the sun rose, as the fog cleared. And like a dream, the waking cliffs glowed orange and the sand lit up silver and the sky, still pale violet was full and open.”

Throughout the novel, aspects of nature play a symbolic role, not in terms one associates with the pathetic fallacy, but as a parallel to the lives of the characters – the multi-faceted symbol of water; the abalone with its ugly exterior and its beautifully vibrant interior shell; sharks, shark teeth, and shark eggs; the act of surfing itself, and fire and light as elements, especially the “southern lights,” or Auroras, and the dawn. The novel’s compression and the simplicity of its language make its beautiful images and its horrors that much more vibrant, its messages clear, while its natural dialogue makes the young characters both believable and memorable. Lovers of literary fiction, book clubs, and teachers will find this powerful debut novel a never-ending source of lively discussion.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears is from https://www.hodder.co.uk/

The map of Tasmania may be found here. Double-click to enlarge. Note the location of Bruny Island in the far south. It is an important location throughout the novel. Cloudy Bay is located on Bruny Isl. http://www.lonelyplanet.com/

Abalone diving is found here: http://best-diving.org/

The SouthernLights are shown on http://www.hotspotmedia.co.uk/ They appear just before the turning point in the novel when Harry sees them at night from his bed.

Cloudy Bay, a major symbol, is located on Bruny Island appears on http://tasmania.bushwalk.com/ “The water was calm, resting and waiting and letting them pass. Just the right amount of wind to sail without having tp work hard, without having to work at all. They moved silently into the bay and through the thinning mist. Cloudy Bay looked brand new. Just born, the outlines becoming sharp as the sun rose, as the fog cleared. And like a dream, the waking cliffs glowed orange and the sand lit up silver and the sky, still pale violet was full and open.”

The abalone shell appears on http://www.fortbragg.com/