“I envy the winds, the water, and the birds whenever I think of them. They blow, flow, and fly; they all get to leave, whereas, in spite of my two quick legs, I am condemned to stay among the mountains and the river valleys, not much different from a tethered horse.” Dshurukuwaa, main character of the novel (and real name of Galsan Tshinag).

There are not many times when one can say that a novel – or series of autobiographical novels, in this case – is truly unique, something written from so personal and unusual a perspective that it becomes a completely new experience for the reader, yet Galsan Tschinag has succeeded in accomplishing this. Born into the nomadic Tuvan culture of Mongolia in 1944, Tschinag, like his parents and grandparents, grew up following the seasons with his sheep and yaks and living with his extended family in a collapsible yurt as part of a small community (ail) which moved from the mountains to the steppes and back so that the animals could feed. With the eyes and ears of a poet, Tschinag recreates his life in three volumes: The Blue Sky (2006), about his first eight years living with his family in their yurt in the Altai Mountains, shows his energy, his intelligence, and his sensitivity to the mysteries of life, which he has learned through Tuvan myths, stories told by family, and his own observations of the natural spirits so tangibly present in all aspects of the natural world around him.

There are not many times when one can say that a novel – or series of autobiographical novels, in this case – is truly unique, something written from so personal and unusual a perspective that it becomes a completely new experience for the reader, yet Galsan Tschinag has succeeded in accomplishing this. Born into the nomadic Tuvan culture of Mongolia in 1944, Tschinag, like his parents and grandparents, grew up following the seasons with his sheep and yaks and living with his extended family in a collapsible yurt as part of a small community (ail) which moved from the mountains to the steppes and back so that the animals could feed. With the eyes and ears of a poet, Tschinag recreates his life in three volumes: The Blue Sky (2006), about his first eight years living with his family in their yurt in the Altai Mountains, shows his energy, his intelligence, and his sensitivity to the mysteries of life, which he has learned through Tuvan myths, stories told by family, and his own observations of the natural spirits so tangibly present in all aspects of the natural world around him.

His second novel, The Gray Earth (2010), continues his story as dramatic changes occur in the 1950s, not just to him and his family but to his culture and to all of Mongolia, as the Russians take over their lands and systematically subvert the local cultures and their beliefs in spiritual powers, in part through the requirement that the brightest children attend Russian boarding schools for nine months a year, returning home only for summer work. The third novel, The White Mountain (scheduled for release in April, 2015), continues the life of the main character, Dshurukuwaa, as he completes school in Mongolia and is sent by the Russians to Leipzig, where he continues his education and eventually obtains his doctorate. There he begins writing (in German) in an effort to save the culture he remembers in Mongolia. Now in his seventies, Tschinag tells us in the Afterword to The Blue Sky, that he has returned to Mongolia, and “With my shaman’s whisk, a truncheon, or a laptop [!], I alternate between living in the indigenous culture of the post-socialist Tuvans [in the mountains and in Ulan Baatar]…and the enlightened state monopoly of Western Europe.”

As The Gray Earth opens, Dshurukuwaa/ Tshinag is eight years old, and already he has determined to become a shaman, with the aid of an aunt by marriage, Aunt Purwu. When he oversteps and intervenes in a ceremony being conducted by Aunt Purwu to drive out an evil spirit, however, his parents believe that he “has done worse than bring shame to the family – [he] has enraged the blue sky.” The night of his childish intervention has led to the killing of a dozen sheep by wolves, and they believe it is his fault. Though he swears off shamanizing, he still cannot keep himself from chanting when he is outdoors, calling out to the spirits, and using the poetry which frequently overcomes his soul to praise and honor them.

Unfortunately for him, he is overheard one day by his much older brother, who has returned home unexpectedly from the Russian boarding school where he is the principal. He announces to the parents that Dsurukuwaa has “played the baby long enough – it has to stop. Anyone who makes rhymes on death and the devil and fills the sky and the earth with his shouting can learn a few measly letters and numbers,” and he convinces them to let him bring the boy to the boarding school where another older brother and sister are already in attendance. The boy “feels ambushed.” When his sister and brother went to school, “they looked dazzling, wrapped from head to toe in colorful brand-new clothes Mother had sewn throughout the summer. Father himself had led them away.” He, however, is in rags. “My headscarf is frayed and stained with squirrel blood and fish slime,” and he hopes no one will see him. Frightened and convinced that he is truly different, he arrives at the school and finds it a “prison,” a word which takes on new meanings when he tries to escape the school, gets caught, and ends up beaten and thrown into the equivalent of a real prison at the age of eight.

Larches with Altai Mountains in background. One offensive of the head of the school involves cutting down the larches nearby, which stimulates outrage first, then surrender by the students.

Galsan Tschinag’s sensibilities dominate this novel/memoir, but he never loses sight of his childhood point of view, even as he recreates the political climate of Mongolia under the Russian occupation and the very real areas in which the Russian goals conflict with the inherent spirituality of many of the students in the school. For the Russians, only the pragmatic, present, and achievable ends which govern both the school administration and the occupying forces, have any value, and they use their allies, the Kazakhs, to enforce these goals. Someone like Dshukurukuwaa/ Tshinag, with a strong awareness of the spiritual values inherent in the sky, the land, and the mountains, must either keep his mouth shut or risk all. Before long, the “chinks” in the armor of those Mongolians who seem to be cooperating fully with the Russians appear, as circumstances arise in which one or more of them needs the help of a shaman to fend off devastating illness or physical danger.

Chalama, colored cloths placed on a tree in a sacred place, symbolize reverence for the universe, the grandeur, beauty, and wisdom of nature.

While the boy suffers alone and tries to survive his new environment, he also wants to learn, and he is so intelligent that he is able to straddle the line between the old and the new ways, at least in public. The vibrant and sympathetic depiction of peripheral characters with whom Dshurukuwaa comes into contact, many of them lonely people without his own inner resources, adds to the drama of this novel and conveys the many levels on which the fight to preserve or destroy the “alien” culture of the Tuvans takes place. Infighting, as one person cooperating with the authorities tries to save himself by blaming another, will sound familiar, and as those in charge set about instituting a series of “offensives” to emphasize the power and influence of the Russians, they set up the conditions which result in a dramatic denouement affecting Dshurukuwaa and his family which nevertheless feels natural despite its obvious symbolism. Katharina Rout’s translation helps bring this novel to life and makes each character feel like “one of us” on the human level, despite the obvious differences in culture. Powerful and enlightening.

ALSO by Tschinag: THE BLUE SKY

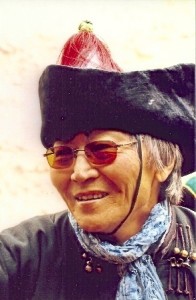

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.lebensraum-kunst.de

The Mongolian boy is shown on http://worldexpeditions.co.uk

The Altai Mountains with a yurt may be found on http://www.filmapia.com/

The larches on the Altai are from http://www.russiawanderer.com/

Chalama, brightly colored cloths on a tree on a sacred place represent reverence for the universe and the grandeur, beauty, and wisdom of nature. http://tyulyush.wordpress.com/