“One mustn’t have human affections–or rather one must love every soul as if it were one’s own child.”

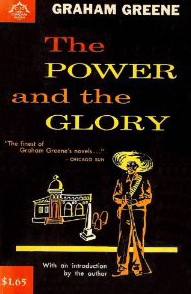

Graham Green e’s most elaborate and personal examination of the good life–and the role of the Catholic church in teaching what the good life is–revolves around an unnamed “whiskey priest” in Mexico in the 1930s. Religious persecution is rife as secular rulers, wanting to bring about social change, blame the church for the country’s ills. When the novel opens, the church, its priests, and all its symbols have been banned for the past eight years from a state near Veracruz. Priests have been expelled, murdered, or forced to renounce their callings. The whiskey priest, however, has stayed, bringing whatever solace he can to the poor who need him, while at the same time finding solace himself in the bottle.

e’s most elaborate and personal examination of the good life–and the role of the Catholic church in teaching what the good life is–revolves around an unnamed “whiskey priest” in Mexico in the 1930s. Religious persecution is rife as secular rulers, wanting to bring about social change, blame the church for the country’s ills. When the novel opens, the church, its priests, and all its symbols have been banned for the past eight years from a state near Veracruz. Priests have been expelled, murdered, or forced to renounce their callings. The whiskey priest, however, has stayed, bringing whatever solace he can to the poor who need him, while at the same time finding solace himself in the bottle.

Constantly on the move, the priest suffers agonizing conflicts. His sense of guilt for the past includes a brief romantic interlude which has produced a child, and though he recognizes that he is often weak, selfish, and fearful, he still tries to bring comfort to the faithful. Pursued by a police lieutenant who believes that justice for all can only occur if the church is destroyed, and by a mestizo, who is seeking the substantial reward for turning him in, the desperate priest finally decides to escape to a nearby state in which religion is not banned so that the police will stop killing hostages taken in the villages he has visited.

The police pursuit of the priest is paralleled by their pursuit of a “gringo” murderer, a man so base that he thinks nothing of murdering children, yet the priest even sees value in this man’s life, and when the gringo, the mestizo, the lieutenant, and the priest finally come together, Greene’s philosophical and religious analysis reaches its climax. For all their faults, the priest is often heroic, the murdering gringo still has a soul worth saving, the mestizo (a Judas figure) offers the priest a better chance to see God, and the lieutenant eventually sees the priest as a human, not simply as a symbol.

Greene’s novel is beautifully constructed–intricate, filled with symbols and parallels, yet often sensitive and moving. Though the action moves through an almost unremittingly bleak landscape and the sense of dread is positively palpable throughout, the novel eventually reveals the “power” and the “glory” of faith. In this sense, the novel is as much a philosophical and religious tract–specifically an examination of the Catholic faith–as it is a human story. While some may find the novel dogmatic and the priest’s agonized self-examination sometimes tedious, others will find the novel uplifting and inspiring.

Notes: The film version of this novel stars Alec Guiness, Maureen O’hara, and Burl Ives.

Also reviewed here: OUR MAN IN HAVANA

and THE THIRD MAN