Note: Author Hisham Matar was WINNER of the Pulitzer Prize for Biography/ Autobiography in 2017 and was also WINNER of the Rathbones Folio Prize and WINNER of the Jean Stein PEN America Award for this memoir.

“Declarative statements such as “He is dead” are not precise. My father is both dead and alive. I do not have a grammar for him. He is in the past, present, and future. Even if I had held his hand, and felt it slacken, as he exhaled his last breath, I would still, I believe, every time I refer to him, pause to search for the right tense. I suspect many men who have buried their fathers feel the same…I live, as we all live, in the aftermath.”—Hisham Matar, on how it feels when a kidnapped parent disappears, never seen again.

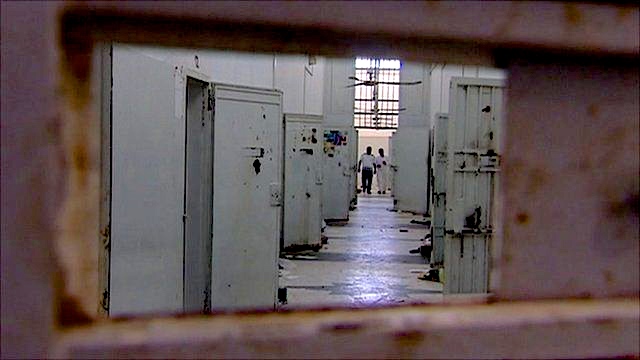

In this memoir, Hisham Matar at last tells his own story and the aftermath of his father’s disappearance and detention at the Abu-Salim Prison, one of the most vicious prisons in the world under Muammar Qaddafi in Libya. In his two novels prior to this memoir, he has dealt with some of the issues from a fictional point of view. His debut novel from 2006, In The Country of Men, tells the story of a young boy living in Tripoli, Libya, while his father works with the resistance to oust Qaddafi. With a mother who drowns her sorrows in alcohol, and a father who is often away, the boy grows up lonely and lost. Matar’s second novel, The Anatomy of a Disappearance, tells more of his own story, though the author is not yet ready to reveal all the specific horrors. Here in an unnamed country which greatly resembles Iraq, he once again tells of a young lost boy whose mother dies when the boy is nine and living in exile in Egypt with his family. When he is fourteen, he goes to England to boarding school, and his father is mysteriously abducted by another power. Taught to keep a stiff upper lip, the boy has literally no one with whom he can share his feelings, and he receives no information about his father, either then or later, growing up in a netherworld without parents to help him and without the ability to ask for help.

In this memoir, Hisham Matar at last tells his own story and the aftermath of his father’s disappearance and detention at the Abu-Salim Prison, one of the most vicious prisons in the world under Muammar Qaddafi in Libya. In his two novels prior to this memoir, he has dealt with some of the issues from a fictional point of view. His debut novel from 2006, In The Country of Men, tells the story of a young boy living in Tripoli, Libya, while his father works with the resistance to oust Qaddafi. With a mother who drowns her sorrows in alcohol, and a father who is often away, the boy grows up lonely and lost. Matar’s second novel, The Anatomy of a Disappearance, tells more of his own story, though the author is not yet ready to reveal all the specific horrors. Here in an unnamed country which greatly resembles Iraq, he once again tells of a young lost boy whose mother dies when the boy is nine and living in exile in Egypt with his family. When he is fourteen, he goes to England to boarding school, and his father is mysteriously abducted by another power. Taught to keep a stiff upper lip, the boy has literally no one with whom he can share his feelings, and he receives no information about his father, either then or later, growing up in a netherworld without parents to help him and without the ability to ask for help.

In this memoir, Hisham wastes no time, going straight to the heart of his life and telling the whole story, showing clearly the effects of the very real traumas which he has never fully explored, and the fears and insecurities which have dominated his life as a result. As the memoir opens in March, 2012, forty-one-year-old Matar, and Diana, a photographer, who have been living in New York, are at the airport in Cairo, waiting to take off for Benghazi. He is nervous because he and his family left Libya for exile in 1979, and he has never returned. His father, Jaballa Matar, worked for the Libyan government as first secretary to the Libyan Mission to the United Nations in 1970, and Hisham was born that year in New York. After three years, he, his father, mother, and older brother Ziad, returned to Libya, as Qaddafi was coming to power. Jaballa Matar, who opposed many of Qaddafi’s policies in the late 1970s, fell victim to Qaddafi’s ambitions. With their lives endangered, the family escaped from Libya for Egypt in the late 1970s, and Hisham did much of his early schooling there.

In this memoir, Hisham wastes no time, going straight to the heart of his life and telling the whole story, showing clearly the effects of the very real traumas which he has never fully explored, and the fears and insecurities which have dominated his life as a result. As the memoir opens in March, 2012, forty-one-year-old Matar, and Diana, a photographer, who have been living in New York, are at the airport in Cairo, waiting to take off for Benghazi. He is nervous because he and his family left Libya for exile in 1979, and he has never returned. His father, Jaballa Matar, worked for the Libyan government as first secretary to the Libyan Mission to the United Nations in 1970, and Hisham was born that year in New York. After three years, he, his father, mother, and older brother Ziad, returned to Libya, as Qaddafi was coming to power. Jaballa Matar, who opposed many of Qaddafi’s policies in the late 1970s, fell victim to Qaddafi’s ambitions. With their lives endangered, the family escaped from Libya for Egypt in the late 1970s, and Hisham did much of his early schooling there.

While in Cairo, the family sets up the situation with which Hisham must deal for the rest of his life. His father, in Egypt, is obsessed with the past and the future and with returning to help remake Libya. His mother is devoted to the present. When Jabbar Matar is kidnapped in 1990, while the family is in Egypt, they believe that he is being kept hidden in Egypt. It is only later, after they receive a letter from him in 1993, that they find out he has been imprisoned in Abu-Salim Prison in Benghazi, famous for its horrors, for three years, and that the Egyptian military participated in his kidnapping and extradition. In the meantime, his brother has had to try to escape a kidnapping attempt at his boarding school in Switzerland, and he, himself, has been at school in England under an assumed name. No one there, except for one faculty member knows who he really is and what his background is. Not only is his father a mystery, but he, himself, has become one, too.

Hope rises that a mass grave outside the prison will reveal the identities of the 1270 massacred men.

As stories leak out about Abu-Salim and the tortures inflicted on its inmates, Hisham becomes haunted by what his father is/was living through during his captivity. Qaddafi’s policy has always been that when one member of a family offends Qaddafi, the entire family is responsible, and four members of Matar’s immediate family have also been seized and imprisoned in Abu-Salim. Occasionally, one of them is able to smuggle a letter out, and Jabbar manages to get three letters out, up to 1993. After this, however, nothing is learned, no matter how hard Hisham works to find out information. He does hear that a former prisoner was able to talk with his father in 2002, after a massacre of 1270 prisoners took place at the prison in 1996. With his hopes high, Hisham seeks out that man – and everyone else he can think of – for further information.

Matar seeks out Titian’s “The Martyrdom of St. Lawrence,” in Italy, after he returns from his visit to Libya. Click here for enlargement.

Matar’s story is enhanced by constant flashbacks which broaden the scope and the cast of characters, making them come more fully alive. The past history of Libya and its connections with Italy, and later Fascist Italy under Mussolini, reveal the genocide of the Libya’s tribal populations even in the 1920s, as tens of thousands die, a circumstance which makes the country’s death toll under Qaddafi seem to fit the country’s pattern of murder. Libya’s relationship with Tony Blair’s England while Qaddafi is in power, comes under close scrutiny here, and Hisham Matar clearly believes that the attempt of Blair to form some kind of relationship with the dictator made circumstance worse, not better. In the meantime, Matar is busy using his own connections to try to find out the fate of his father, one way or the other. In 2003, he writes to Seif Qaddafi, son of Libya’s president, and over a period of many months, he is able to gain some new information. In the process, he is able to secure the release of some family members. With no news regarding his father, Matar is forced to form his own conclusions, and in the process, he learns much about himself and the compromises he himself may be willing to make or not make. This powerful memoir treats the subjects of memory and loss, innocence and guilt, power and vulnerability, and ultimately love and hope, giving the reader new insights into how one man eventually manages to cope with his past, present, and future.

Also by Matar: ANATOMY OF A DISAPPEARANCE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.revistaarcadia.com/

A view of Abu-Salim Prison may be found on http://www.bbc.com/

More information about the possible site of a mass grave behind Abu-Salim Prison may be found here: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/

Titian’s “The Martyrdom of St. Lawrence” became a destination point for Hisham Matar upon his departure from Libya at the end of the novel. Click here for enlargement. http://www.dailymail.co.uk