“ I was in the grips of the worst of all terrors, as if death were breathing alongside me, as if the snores of sleeping beauty were the blast of the trumpet announcing the arrival of the black heralds, what a thought, for fear distorts everything.”

An unnam ed writer is hired by a friend who works with the human rights office of the Catholic Church of an unnamed Latin American country to edit and proofread eleven hundred pages of testimony—“the memories of the hundreds of survivors of and witnesses to the massacres perpetrated in the throes of the so-called armed conflict between the army and the guerrillas.” During the 1970s and 1980s, the army declared that the indigenous Indians who had lived in remote Mayan villages for hundreds of years were anti-government leftists, and soldiers conducted widespread genocide wiping out hundreds of villages and killing over a hundred thousand people. Now, many years later, the human rights office at the cathedral plans to publish the survivors’ testimonies for the first time. One section of the report, detailing how the army intelligence services operate, is considered so explosive that this section will be added to the finished book the day it goes to press, when it is too late to stop it. Writing in the first person, the writer/editor, an atheist, confesses that he is concerned about the relationship between some members of the church hierarchy and members of the army, who may have directed the massacres, and he trusts no one.

ed writer is hired by a friend who works with the human rights office of the Catholic Church of an unnamed Latin American country to edit and proofread eleven hundred pages of testimony—“the memories of the hundreds of survivors of and witnesses to the massacres perpetrated in the throes of the so-called armed conflict between the army and the guerrillas.” During the 1970s and 1980s, the army declared that the indigenous Indians who had lived in remote Mayan villages for hundreds of years were anti-government leftists, and soldiers conducted widespread genocide wiping out hundreds of villages and killing over a hundred thousand people. Now, many years later, the human rights office at the cathedral plans to publish the survivors’ testimonies for the first time. One section of the report, detailing how the army intelligence services operate, is considered so explosive that this section will be added to the finished book the day it goes to press, when it is too late to stop it. Writing in the first person, the writer/editor, an atheist, confesses that he is concerned about the relationship between some members of the church hierarchy and members of the army, who may have directed the massacres, and he trusts no one.

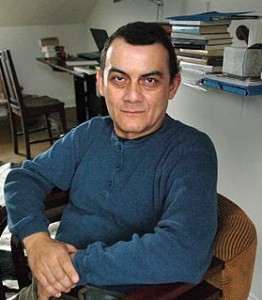

Author Horacio Castellanos Moya, a Salvadoran author whose own work on human rights issues led to his exile from that country, writes here about similar issues in a neighboring country, one in which the Catchiquel, Quiche, and Mam Indians, all descendants of the Maya, are systematically tortured and killed by the government. Eleven hundred pages of testimony from victims’ families, which an editor is reading, include stories of four hundred twenty-two massacres. The editor, whose stream-of-consciousness opinions and emotional reactions involve the reader from the outset, becomes a true character here, his sardonic humor vying for attention with his own paranoia about being pursued by the army, his relentless sexual fantasies and attempted seductions, and his commentary about particularly memorable and poetic sentences that he finds in the testimonies of the uneducated survivors. Self-conscious in the extreme, he constantly worries about what people think of him, especially women, at the same time that, ironically, he imagines writing a novel about a brave civil registrar who dies to protect the truth.

Catchikel (Mayan) family in mountain village

As he reads the dramatic and heart-rending testimonies, he gradually becomes more and more involved with the stories, and he wonders how Joseba, a Basque psychiatrist who compiled and recorded more than half of the original testimony, can maintain his sanity. His own increasing emotional involvement begins to take its toll, the raw sexuality and violence of the documents paralleling, on a smaller scale, the sexual encounters in his own private life and the potential for violence there. The more involved the editor becomes in the stories he reads, the closer he becomes to losing his control and his sanity, and the more ironic his observations become. The horrifying story of Teresa, who works at the cathedral complex, a woman of thirty-three who was captured, gang-raped, non-stop, for a week and impregnated when she was sixteen, is juxtaposed against the speaker’s annoyance at contracting a venereal disease from a recent partner and his fear that the woman’s Uruguayan boyfriend, a soldier, will arrest and torture him. His behavior after escaping the city to a Catholic retreat to complete his work in seclusion, is irrational and suggests he has become as “senseless” as the violence which has torn the country.

Nobel Peace Prize winner Rigoberta Menchu

Castellanos Moya creates a powerful work of fiction from some of the western hemisphere’s most horrendous brutality, giving enough detail to shock the reader into questioning how human beings could not only commit some of these atrocities but enjoy the bloodshed in the process. At the same time, however, he is aware of the limits on violence that a reader can comprehend before “tuning out,” a rare quality which he exploits by juxtaposing some of the worst details of torture against images of the absurdities in the speaker’s personal life. This provides a kind of mordant humor, which allows the reader to recover enough equilibrium to tackle the next set of revelations with a fresh sense of outrage. And as the speaker becomes less and less in control, and more and more in fear of his life, his behavior becomes a kind of testimony of its own—the fear generated by a powerful elite which has yet to be punished.

Note: Though the author never mentions the country at the center of this novel, the Cakchiquel (Catchikel), Quiche, and Mam indigenous people, all mentioned by name here, are from Guatemala.

ALSO by Castellanos Moya: TYRANT MEMORY, THE SHE-DEVIL IN THE MIRROR, THE DREAM OF MY RETURN

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Pam Panchak, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: http://www.post-gazette.com

The girl in the center of the photo of a Catchikel family is the only member of her family who speaks Spanish. She is now a ninth grader at a school for which she has won a scholarship from Seeds of Help, a volunteer organization: http://seedsofhelp.org

Though not mentioned in the novel, Rigoberta Menchu, a thirty-three-year-old Quiche woman from Guatemala (pictured above), won the Nobel Peace Prize (http://nobelprize.org) for her testimony against the military atrocities there in the 1970s and 1980’s. Her photograph and the amazing story of her efforts on behalf of indigenous people are here: www.womeninworldhistory.com

NOTE: Author Horacio Castellanos Moya, born in Honduras, raised in El Salvador, and exiled from much of Central America, has been resettled in the United States under a program of The City of Asylum in Pittsburgh, which “provides sanctuary to writers exiled under threat of death, imprisonment, or persecution in their native countries.” (Author Russell Banks was President of this organization for many years.) Castellanos Moya is now an Assistant Professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Iowa. A comprehensive interview with Horacio Castellanos Moya appears on http://quarterlyconversation.com