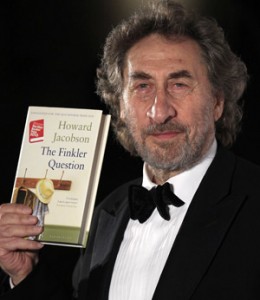

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Man Booker Prize for 2010.

“Before he met Finkler [as a schoolboy], Treslove had never met a Jew. Not knowingly at least. He supposed a Jew would be like the word Jew–small and dark and beetling. A secret person. But Finkler…had a towering manner that made him look taller, and delivered verdicts on people and events with such assurance that he almost spat them out…If this was what all Jews looked like, Treslove thought, then Finkler…was a better name for them than Jew. So that was what he called them privately–Finklers. It took away the stigma.”

If there is tr uly a separate genre known as a “Jewish novel,” then this novel would have to be its crowning achievement. An expansive and wide-ranging novel about the many facets of being Jewish (or “Finklerish,” as Treslove sees it), The Finkler Question examines the lives of three friends: Julian Treslove, a now forty-nine-year-old Gentile, has always been fascinated by all things Jewish, including women. A romantic who has never been able to maintain a relationship, however, Julian has been abandoned by all of the women he’s known in the past, including the two who bore his sons. Sam Finkler, Julian’s former classmate, writes wildly popular (and popularized) editions of philosophical ideas “for all occasions.” Sam is a widower who lost his young wife early, leaving him with three older children. Libor Sevcik, almost ninety, their former teacher, who eventually became a commentator on the entertainment business, is also a widower, having just lost his devoted wife of over fifty years, and his former students have been trying to see him more often because he feels so lost.

uly a separate genre known as a “Jewish novel,” then this novel would have to be its crowning achievement. An expansive and wide-ranging novel about the many facets of being Jewish (or “Finklerish,” as Treslove sees it), The Finkler Question examines the lives of three friends: Julian Treslove, a now forty-nine-year-old Gentile, has always been fascinated by all things Jewish, including women. A romantic who has never been able to maintain a relationship, however, Julian has been abandoned by all of the women he’s known in the past, including the two who bore his sons. Sam Finkler, Julian’s former classmate, writes wildly popular (and popularized) editions of philosophical ideas “for all occasions.” Sam is a widower who lost his young wife early, leaving him with three older children. Libor Sevcik, almost ninety, their former teacher, who eventually became a commentator on the entertainment business, is also a widower, having just lost his devoted wife of over fifty years, and his former students have been trying to see him more often because he feels so lost.

As the three interact and share their lives with each other (and the reader), often hilariously, the author takes the unusual approach of showing how these actions reflect both their interdependencies and their religion–or lack of it. Treslove has come to believe that his own life would be better if only he were Jewish, a belief which causes Finkler to comment, “You don’t know what you are so you want to be a Jew. Next you’ll be wearing fringes and telling me you’ve volunteered to fly Israeli jets against Hamas.” And yet when Julian does go out on the town one evening, he is robbed and roughed up by an assailant who suggests that Julian is being robbed because he is Jewish (!), an event which brings home to Julian the issue of anti-Semitism.

The continuing subject of anti-Semitism is examined from an unusual perspective here. When Libor accuses Finkler himself of having Jewish friends who are anti-Semites, he refuses to acknowledge it. “It’s not peculiar to Jews to dislike what some Jews do,” he comments, and he admits he is particularly upset by many Israeli actions, but Libor has the last word in the argument: “No,” he says, “but it’s peculiar to Jews to be ashamed of it. It’s our schtick. Nobody does it better.”

In another plot line, the feckless Julian meets Hephzibah Weitzenbaum, Libor’s great-great-niece, and he believes that he may finally have found his soul-mate. Working on a Museum of Anglo-Jewish Culture, she emphasizes what the Jews have achieved in England, rather than what they have undergone, and she persuades Julian to help out, He begins to study Jewish thought by reading Maimonides (with enormous difficulty) and though he starts thinking of himself as Jewish, he cannot seem to enter the “club.” “It was like being a child among adults; not unloved but unlistened to. At best humoured. He wasn’t the real McCoy, that was what it came to. Not only wasn’t he a Jew, he was a jest to Jews. The real McGoy.”

In another plot line, the feckless Julian meets Hephzibah Weitzenbaum, Libor’s great-great-niece, and he believes that he may finally have found his soul-mate. Working on a Museum of Anglo-Jewish Culture, she emphasizes what the Jews have achieved in England, rather than what they have undergone, and she persuades Julian to help out, He begins to study Jewish thought by reading Maimonides (with enormous difficulty) and though he starts thinking of himself as Jewish, he cannot seem to enter the “club.” “It was like being a child among adults; not unloved but unlistened to. At best humoured. He wasn’t the real McCoy, that was what it came to. Not only wasn’t he a Jew, he was a jest to Jews. The real McGoy.”

As the author rotates the focus of the novel among the three men, he creates many intimate scenes which reveal the nature of “Jewishness” as both a religious and cultural identity. With self-mocking humor (much of which undoubtedly escapes the notice of non-Jewish readers, such as myself), he creates lively scenes with conversations both serious and farcical. His inclusion of real contemporary events with references to real people, including President Obama, provides a real-world context for the philosophizing of the novel and illustrates the lack of uniformity among the points of view of these Jewish thinkers, showing them to be as varied in their points of view, even regarding Israel, as are non-Jewish thinkers. The novel will carry special appeal, I’m sure, for Jewish men and women who are already familiar with these issues, but for curious “others,” it provides many insights and valuable new points of view.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Luke MacGregor/Reuters, was taken at the Man Booker Award Ceremony, is from: www.cbc.ca

Sam Finkler conducted the meetings of the ASHamed Jews at the Groucho Club in Soho. Photo from: www.thegrouchoclub.com

Beachy Head, a location which appears in the novel several times, is depicted here: Photo by Speller/Milner Design 2004: http://www.findon.info