Note: Howard Norman is a WINNER of the Lannan Award for his “significant contributions to English-language literature,” and has twice been NOMINATED for the National Book Award.

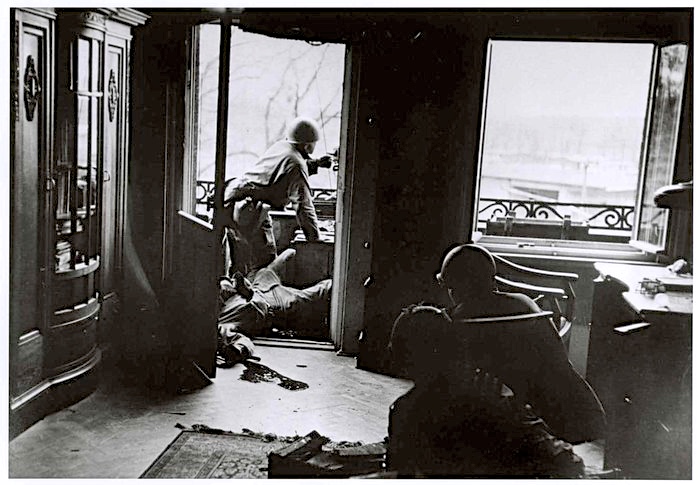

‘Death on a Leipzig Balcony,’ by Robert Capa, was the first item [up for sale]. The auctioneer had just said, … ‘taken on April 18, 1945,’ when my mother Nora Ives – married name, Nora Ives Rigolet – walked almost casually up the center aisle and flung an open jar of black ink at the photograph. I heard, ‘No, it can’t be you!’ But it was my own voice, already trying to refute the incident.”

Jacob Rigolet, the speaker, is attending a 1977 auction of photographs on behalf of his employer, Mrs. Esther Hamelin, a well-known collector of vintage photographs – literally doing her bidding at auction around the world. Suddenly, he is horrified to see his estranged mother, Nora Rigolet, walk up the aisle of the auction hall. Without warning, she throws a pot of black ink at a photograph taken by photographer Robert Capa during a World War II battle, “Death on a Leipzig balcony.” Jacob’s mother, the former Head Librarian of the Halifax Free Library in Nova Scotia, had been “safely tucked away” at the Nova Scotia Rest Hospital, following a breakdown three years previously, and Jacob has not seen her for over a year. He himself has been busy working part-time at the Free Library and, for the past two years, living most of the time in a cottage behind Mrs. Hamelin’s Victorian home. In one of the novel’s many ironies, it is Jacob’s fiancée, Martha Crauchet, a detective with the Halifax Regional Police, who is in charge of Nora Rigolet’s interrogation at the police station. With no sense of fear, Nora answers their questions but provides little insight into why she destroyed this photograph.

The novel which develops from this opening scene, described on the book jacket as “a nod to classic noir,” is noir primarily in its ironies, rather than its overall style. An air of fun and good humor prevails for most of the novel, even as universal themes of right and wrong, and good and evil, begin to appear throughout. One of the two policemen who interrogates Nora, for example, is concerned about her “willful destruction of private property,” wanting to leave the more serious questions of her sanity “up to the shrinks.” “That behavior’s been around since the Old Testament,” he announces. The other officer is not so sure that’s the right approach to the crime, however, responding with, “Considering Halifax isn’t mentioned in the Old Testament…what you said doesn’t fall into our purview.” Their offbeat banter about crime continues, as they set themselves up as somehow “different” from people like librarians who call the police when “some dangerous criminal [has] moved the A volume of the Encyclopedia Britannica…[and then] referred to it as a ‘booknapping,” concluding that “librarians are control freaks.” Only Martha, Jake’s fiancée/detective, is initially concerned with why Nora destroyed this particular photograph, a question which goes unanswered (and remains unanswered for most of the book). Without making ponderous statements or calling attention to Big Meanings, author Howard Norman quietly introduces interpretations of right and wrong and the compromises they inspire while also noting the tendency of people to notice differences more often than similarities when forming judgments.

By page fifteen, Jacob’s life becomes even more complex, and he learns new truths in a chapter entitled, “So You’re Telling Me I Was Born in the Halifax Free Library and the Man I thought Was My Father Was Not Really My Father.” His whole past, he learns, has been a lie. Bernard Rigolet, to whom his mother was married, had gone off to war in Germany, and Nora had become pregnant by someone else while he was gone. This new lover, a former member of the Halifax Police, is reportedly still alive but “Wanted,” with a criminal record. His crime has been a hate crime, and as years have passed, post-war, others with similar attitudes have also attracted attention in Halifax. Jacob spends little time pondering the moral issues and themes, however. He and Martha are in love and planning to be married, and that is what matters to him. Lies and truth, attitudes toward differences, and how one copes all impact him directly, however, and they continue to loom within his life and that of his mother.

This photograph, “Death on a Leipzig Balcony” is in The Robert Capa and Cornell Capa Archive, Gift of Cornell and Edith Capa, 1992. Click to get to the link and then click again to see the enlargement.

Other issues emerge in new scenes and plot threads. Throughout the novel, Martha and, eventually, Jake, are obsessed with listening to all the episodes of an old radio program entitled “Detective Levy Detects,” in which Levy and his love, Leah Diamond, participate in time travel, moving back to the forties to participate in noir plots in which they often accept help from criminals as they solve their cases – “You don’t even have to tell nobody we’re the ones upped your crime-fighting IQ. That way we get to help eliminate some of the competition – see, a life of crime is very competitive – and you get all the credit.” Scenes from this show offer some comic relief and a change of pace while also echoing the ideas of crime, right and wrong, and whether there are absolute standards of judgment. Jacob himself has had a problem with this in that past, and he once took the easy route regarding a man who outbid him at an auction, causing him to lose his job – not failing to win the desired photograph, but for being dishonest, in her opinion.

The Halifax Free Library, through 1948, existed as a small section of the second floor of the Halifax City Hall. This building, known as the Rathaus, would have been where Nora Rigolet worked.

The novel, a delight to read, with its intriguing plots and subplots, its very human characters, and its light touch with moral issues, comes to a surprising grand finale which earns the label “noir,” a conclusion which is presaged by one of the radio programs in the “Detective Levy Detects” series, “I Couldn’t Bear It If Something Terrible Befell Leah Diamond,” a story in which Leah is being stalked and Levy takes questionable action resulting in a police action with serious casualties. What enlivens the conclusion on an emotional level, however, is a series of four letters written by Bernard Rigolet to his wife Nora from Germany as he sees concentration camps, participates in battle, and sees death up close. In his tragically beautiful final letter to Nora, he feels and speaks more directly to her than ever before. Her own tormented history becomes clearer, and she begins to face some of her demons. In a loving and lovely commentary, she discusses her fears and failings and what she thinks she needs to do to earn a full life, if such a life is even possible for her. In a book which deals with characters who do not do much thinking, at first, the book concludes with many new insights and a new relationship between the characters and the reader.

In 2014 the Halifax Free Library was incorporated into this dramatic and well-equipped new library, known as the Halifax Central Library.

Photos: The author’s photo appears on http://www.kcrw.com/

The auction which opens the action of this novel takes place at the Lord Nelson Hotel, which appears in other scenes in this novel. www.tripadvisor.ca

“Death on a Leipzig Balcony” by Robert Capa is the photograph which Nora, for her own reasons, decided to cover with black ink, horrifying her son and everyone else at the auction. https://www.icp.org

According to Wikipedia: In 1948, Halifax had “a single over-crowded, under-equipped room at the end of a corridor” located in the City Hall building, known as the Rathaus. Even smaller towns nearby provided more extensive library services than Halifax at this time. Nora worked here when she first started working at the library during World War II, and Jake may have been working here even as late as 1977 when he, too, worked at the library. Wikipedia indicates that “several decades” passed before any new library was built. https://commons.wikimedia

In 2014, Halifax opened this new library, known as the Halifax Central Library which greatly expands services and provides a gathering place for the community. https://commons.wikimedia.org