Note: British author Ian McEwan has been NOMINATED for the Man Booker Prize six times, and was WINNER of that prize in 1998 for Amsterdam.

“I count myself an innocent, unburdened by allegiances and obligations, a free spirit, despite my meagre living room. No one to contradict or reprimand me, no name or previous address, no religion, no debts, no enemies. My appointment diary if it existed, notes only my forthcoming birthday. I am, or I was, despite what the geneticists are now saying, a blank slate.”—unnamed, unborn child, the narrator/ main character of this novel.

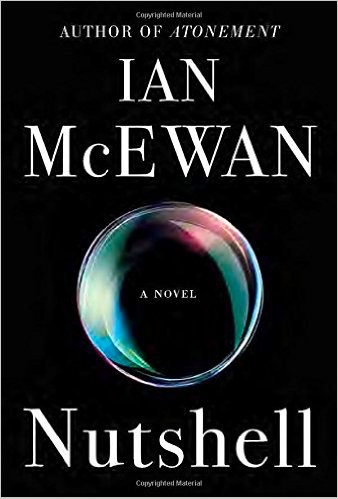

I have to admit that when I read the premise of this novel, I cringed, thinking that it sounded too “cute”- even effete – to be taken seriously; author Ian McEwan relates this entire novel from the point of view of an unborn baby, nine months in the womb. Describing his “living room” with its cramped quarters within his mother Trudy’s belly, the unborn child points out that he has a surprising amount of control over his life, that he can overhear every conversation involving his mother, that he can participate in every physical act involving her, and that he likes his father, John, a poet, even though his mother has left him for a new lover, his father’s younger brother Claude. When the baby gets bored, he knows he can start kicking so that his mother will turn on the radio to calm him down. He enjoys participating in the excessive drinking of alcohol which his mother and her lover Claude enjoy, and though he knows that alcohol may lower his intellect, he finds himself sometimes “pulling on his cord” for “another round.”

I have to admit that when I read the premise of this novel, I cringed, thinking that it sounded too “cute”- even effete – to be taken seriously; author Ian McEwan relates this entire novel from the point of view of an unborn baby, nine months in the womb. Describing his “living room” with its cramped quarters within his mother Trudy’s belly, the unborn child points out that he has a surprising amount of control over his life, that he can overhear every conversation involving his mother, that he can participate in every physical act involving her, and that he likes his father, John, a poet, even though his mother has left him for a new lover, his father’s younger brother Claude. When the baby gets bored, he knows he can start kicking so that his mother will turn on the radio to calm him down. He enjoys participating in the excessive drinking of alcohol which his mother and her lover Claude enjoy, and though he knows that alcohol may lower his intellect, he finds himself sometimes “pulling on his cord” for “another round.”

If, by now, you have a little smirk on your face, you will have seen how wrong I was to have dismissed this novel initially as a clever trick. In fact, McEwan creates a real tour de force here, a novel that is totally unique – certainly bizarre, in many ways, but very funny in its absurdity. The author’s adroit handling of the ironies of its plot and characters keep the reader fully engaged, even as he is revealing the action from the point of view of a particularly precocious unborn baby. The baby’s father, John Cairncross, the poet and head of a failing publishing house, has abandoned his childhood home and leased another house not far away. In debt, he could use the income from the sale of the house he has inherited, but Trudy, his baby’s mother, and her lover Claude, his brother, are currently living in it. Dilapidated and filthy, the house has garbage in the hallway, but no one seems to notice, and John still comes by to visit and to recite poetry to Trudy, hoping she will take him back. Claude, a property developer, dull and vapid, as we learn from the baby-narrator, is noted for his “witless, thrustless dribble,” and he drives the baby crazy with his constant whistling. He “composes nothing, invents nothing,” according to this yet-to-be-born academic snob.

In several places, the baby-narrator sees his mother as a “blonde and braided Saxon shield-warrior,” about to go into battle.

In the first pages of the novel, the baby tells us that his mother and Claude are planning a dreadful event,” but the reader is not told the details of what that event is until after the author has described their characters and laid the groundwork for the action. The baby hears them say that they must act quickly, observes his mother saying that she “can’t do it,” then hears Claude insist that they can. The baby remarks that he himself is “an organ in her body not separate from her thoughts. I’m party to what she’s about to do…As they kiss again she says into [Claude’s] mouth…baby’s first word. Poison.” What bothers the baby most, however, is that Claude also refers to the aftermath of the “event,” when they have “placed the baby somewhere.” Furious, the baby cannot stop thinking about “placed” as the “lying cognate of dumped.” And he knows that “only in fairy tales are unwanted babies orphaned upwards. The Duchess of Cambridge will not be taking me on.” He imagines himself living in public housing with a tattooed mother and her boyfriend’s pungent dog, “raised bookless on computer toys,” and he silently implores his father to rescue him from his Vale of Despond.

Needing courage to take the action he wants to take, the baby-narrator thinks of Franz Reichelt, the Flying Tailor, who in 1912, decided to test a parachute he’d developed. After a long wait to draw courage, he jumped to his death from the Eiffel Tower.

From this scenario within the first forty pages of the book, all the complications evolve for the remainder of the novel. McEwan’s descriptions, often hilarious, keep the reader completely involved with the obvious ironies and absurdities, and as the baby-narrator develops a plan for revenge on his uncle and his mother – not for their plans to poison his father but for their betrayal in wanting the baby “placed” after its birth – the action ratchets up and becomes yet more convoluted. Twists, turns, and surprises galore keep the tension high as the author works his way to the tour de force of an ending. Filled with literary allusions and commentary on the contemporary world, the author creates a delicious new version of some old themes and plot lines.

I have deliberately ignored the clear parallels that McEwan draws between the plot of this novel and Shakespeare’s Hamlet, to give more attention to this novel on its own. McEwan is obviously having great fun as he creates a modern mystery story told by a Hamlet in utero. The result is a light-handed parody of the play and of Gertrude and Claudius (Trudy and Claude) who killed Hamlet’s father, and of Hamlet himself seeking his revenge. This novel stands fully on its own for those who may be unfamiliar with Hamlet, though it will certainly be more fun for those who know the play and recognize some of the hidden references. Trudy and Claude are true villains here, just as Gertrude and Claudius are in Hamlet, and the baby-narrator, the Hamlet of the novel, is not quite sure what he can do to avenge their plans for his father. “To be or not to be…” takes on new and witty meanings when imagined by a confused infant, not yet born. The title of the book, Nutshell, refers to a line from the play in which Hamlet says “I could be bounded in a nutshell, and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams,” a sentiment not completely shared by the baby-narrator in which he offers advice to newborns: “Don’t cry. Look around, taste the air. I’m in London. The air is good, Sounds are crisp, brilliant with the treble turned up.”

ALSO by McEwan, reviewed here: THE COCKROACH . Two earlier books, which I reviewed for another site more than ten years ago, are . SATURDAY and ATONEMENT

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.platform505.com/

The “blonde and braided Saxon warrior” which Gertrude represents to the speaker is from http://www.abovetopsecret.com

Needing courage to take the action he wants to take to avenge his father and himself, the baby-narrator thinks of Franz Reichelt, the Flying Tailor, who in 1912, decided to test a parachute he’d developed. After a long wait to draw courage, he finally jumped to his death from the Eiffel Tower. http://twitika.com

Sir John Gielgud as Hamlet, a far cry from the narrator of this novel: http://libguides.uwlax.edu