“[Sao Paulo] may not be the most beautiful, or the most poetic, or the most formally perfect, but it is the biggest, the loudest, the dirtiest, the most brazen [city in the country]. Twenty million souls and rising, and there is nothing to stop it seeping across its plateau, and nothing to get in the way of its commerce.”

Jame s Scudamore, at age thirty-four, has already achieved the kind of accolades for his first two novels that most authors only dream of. His debut novel, The Amnesia Clinic, won the Somerset Maugham Award and was shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award, the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, the Dylan Thomas Prize and the Glen Dimplex Award. Heliopolis, his second novel, was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize for 2009.

s Scudamore, at age thirty-four, has already achieved the kind of accolades for his first two novels that most authors only dream of. His debut novel, The Amnesia Clinic, won the Somerset Maugham Award and was shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award, the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, the Dylan Thomas Prize and the Glen Dimplex Award. Heliopolis, his second novel, was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize for 2009.

Raised in Brazil, Japan, and the UK, Scudamore sets this novel in Sao Paulo, a city he obviously knows well, revealing his youthful enthusiasm for life, his sharp eye for injustice, and his (perhaps naive) hope for the future in a tale which follows the life of Ludo dos Santos from his childhood till about age twenty-seven. Ludo and his mother, a cook, had been plucked from Heliopolis, the largest favela (slum) in Sao Paulo, and established permanently at the weekend farm to which Zeno “Ze” Generoso, the fabulously wealthy owner of a chain of supermarkets, his British wife Rebecca, and his daughter Melissa travel on weekends. Eventually, Ze adopts Ludo, schools him, and makes him a part of the high life which the rest of Ze’s family takes for granted. Their lives are so rarefied that they almost never set foot on the ground in the city–and do not have to–since they can commute to most of the places they want to go by helicopter, avoiding the danger of the streets and the threat of kidnapping.

Telling Ludo’s story through flashbacks and foreshadowings of things to come, Scudamore quickly establishes the atmosphere and the dramatic contrasts between the lives of the poor and those of the rich in a city with virtually no middle class. In a touching and revealing scene at the opening of the novel, Ludo, in his twenties, is killing time during a traffic jam before work, exploring a neighborhood in the process of redevelopment. A fifteen-year-old boy, a grifter, is begging for money from two women in the square. After being rebuffed, he decides to try his act on Ludo. “My mother is dying,” he says. She is in hospital and he needs the taxi fare to get there to say goodbye. When Ludo offers instead to drive him to the hospital, the boy becomes furious, turning on Ludo and saying with caustic irony, “With a change of clothes, a bad night’s sleep and some mud on your face, you’d look just like me.”

Challenged by the boy, Ludo offers him double the amount that he is able to beg successfully from another “mark.” Frantic to gain the money, the boy becomes impatient with his ensuing lack of success and “goes for broke,” approaching a security guard with his demands. Disaster strikes, and Ludo is powerless to stop it. Though he blames himself for what happens, the event is ultimately “just one more frenzied city drama in a thousand, to be forgotten and absorbed into the oozing traffic, and perhaps mentioned in passing over lunch.”

Caught between the world of the favela, which he does not remember, and the world of the rich, to which he feels he does not really belong, Ludo is unsure of his place in the world. More sensitive than the bosses at the ad agency for which he works and infinitely more socially aware than Ze, his adoptive father, he admits that “Sometimes I want to run away from this life to which I have been promoted,” and he sees his life as a maze with ever-narrowing paths. A crisis erupts when Ze decides to create a whole new type of supermarket chain–MaxiBudget–to appeal to the poor in the favelas, taking the food to them for the first time. “Affordable food. Designated food. Official food,” not food which may have been “hanging above the butcher’s block crawling with flies for six hours.” His stepmother Rebecca’s Foundation will help support the effort. Ze, of course, will make a great deal of money selling to a huge new population, an effort which Ludo believes is made primarily to “stop [the poor] from staring hungrily through the windows of our own [regular] supermarkets” rather than from any sense of improving their welfare.

Caught between the world of the favela, which he does not remember, and the world of the rich, to which he feels he does not really belong, Ludo is unsure of his place in the world. More sensitive than the bosses at the ad agency for which he works and infinitely more socially aware than Ze, his adoptive father, he admits that “Sometimes I want to run away from this life to which I have been promoted,” and he sees his life as a maze with ever-narrowing paths. A crisis erupts when Ze decides to create a whole new type of supermarket chain–MaxiBudget–to appeal to the poor in the favelas, taking the food to them for the first time. “Affordable food. Designated food. Official food,” not food which may have been “hanging above the butcher’s block crawling with flies for six hours.” His stepmother Rebecca’s Foundation will help support the effort. Ze, of course, will make a great deal of money selling to a huge new population, an effort which Ludo believes is made primarily to “stop [the poor] from staring hungrily through the windows of our own [regular] supermarkets” rather than from any sense of improving their welfare.

At times the novel seems to approach satire, but Ludo’s voice is too resentful of the patronizing attitudes of the rich toward the poor and too upset at their lack of conscience for the novel to feel much like satire. Ludo feels close to the poor, especially his mother, even though he himself is benefitting from the largesse of the rich and essentially ignoring the poor. On another issue Ludo is especially conflicted. He is in love with his step-sister Melissa. As all these issues, both personal and social, come together, Ludo experiences a belated and almost unique coming-of-age.

Filled with vibrant life, dramatic scenes, and many revelations about individual and social responsibility, the novel does verge on melodrama in a number of places, and some coincidences are disappointingly unrealistic. Overall, the novel has direction and a strong sense of purpose, despite the somewhat enigmatic and “thin” ending. The author presents a vision of life in Sao Paulo over a span of fifteen years and describes, among other things, the efforts of the city and country to improve life in the favelas (an effort further described in the photo essay for which I have provided a link in the Notes). Even as people live and die in poverty, often seeing little change and less hope, the author, Ludo’s alter-ego, refuses to accept the status quo–”Everything will be different tomorrow,” he believes.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on www4.fnac.com.

The sharp contrast between rich and poor is shown in this dramatic photo from www.neogaf.com. It is important to note that the favela beside the luxury apartment house is actually relatively “upscale,” with cars in driveways and little trash, and some might classify as a “neighborhood” and not a slum, despite the crowded buildings.

A wonderful photo essay that highlights the work of Bete Franca of the Municipality of Sao Paulo to improve infrastructure and permanently change lives for the better appears here: http://affordablehousinginstitute.org These improvements were financed by the World Bank.

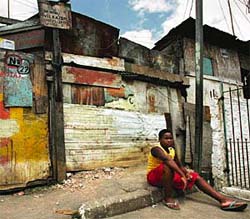

The last photo by Jess Hurd is taken in the real favela of Heliopolis in Sao Paulo. www.reportdigital.co.uk

The author’s website with several interviews is here: www.jamesscudamore.com