The author raises more questions than he answers.

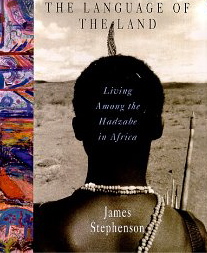

James Stephenson’s memoir about the Hadzabe in Tanzania, one of the last tribes of hunter-gatherers, is fascinating, though not always in ways the author probably intended. As much about the 27-year-old author and the casual romanticism with which he plunges into life in another culture as it is about the death throes of a Stone Age tribe being overtaken by “progress,” the author announces at the outset that this is “a journey greater than [him]self, a journey that has chosen [him].”

Stephenson’s memoir about the Hadzabe in Tanzania, one of the last tribes of hunter-gatherers, is fascinating, though not always in ways the author probably intended. As much about the 27-year-old author and the casual romanticism with which he plunges into life in another culture as it is about the death throes of a Stone Age tribe being overtaken by “progress,” the author announces at the outset that this is “a journey greater than [him]self, a journey that has chosen [him].”

Propelled initially by visions and fever dreams, New Yorker Stephenson, called “Jemsi” by the Hadzabe, participates in all phases of their lives–the hunting and gathering, the long, thirsty treks in the bush, the seemingly endless drinking of intoxicating pombe, the meals of everything from monkey brains to baboon marrow, and dangerous, unprotected sex with camp followers, who believe that baboon oil will protect them from AIDS.

The reader cannot help but admire the gusto with which the author approaches this life, his genuine fear that this culture will soon die completely, and his reverence for their beliefs, their connection to the land, and their ancestors. But it’s impossible also not to wonder about the authenticity of his observations when he is so often paying to accompany the Hadzabe in the bush, when it is his flashlight the Hadzabe sometimes use to blind the small antelope they kill and eat, and when so much of his knowledge seems to come from visions or in dreams.

And he can always escape. During an uncomfortable time of heavy rains, he takes a vacation, flying to Zanzibar, where, he says, the “energy of the stars, the earth, the trees, the animals…all seemed to channel through me…I was creatively on fire and sexually out of control…The ancient man inside me had awakened and was struggling violently with the modern man,” which sounds like a creative way of saying, “The devil made me do it.”

Stating in his preface  that he “came to understand the importance of exaggeration…to create a more universal truth for the listening party,” the author conveys his excitement in a skillful narrative, which often includes striking imagery: of elderly people entering the camp “like slow wakes in still water,” and of walking “through the oracles of singing red birds.” His visions, dreams, and psychic premonitions, however, may cause the reader to pause, wondering if they are part of the exaggeration he finds so important here. And there is unintended irony, with Nubea, an old Hadzabe, mournfully asking, “Why are the forests eaten by the corn and bean?” [p. 176] , while the author, just a few pages later [p. 185], admires the life of a friend in Zanzibar, stating, “One could definitely envy the family’s way of life. They ‘lived’ life on a farm…” In this fascinating story about a modern young man’s attempts to share an endangered life style, Stephenson may raise more questions than he answers.

that he “came to understand the importance of exaggeration…to create a more universal truth for the listening party,” the author conveys his excitement in a skillful narrative, which often includes striking imagery: of elderly people entering the camp “like slow wakes in still water,” and of walking “through the oracles of singing red birds.” His visions, dreams, and psychic premonitions, however, may cause the reader to pause, wondering if they are part of the exaggeration he finds so important here. And there is unintended irony, with Nubea, an old Hadzabe, mournfully asking, “Why are the forests eaten by the corn and bean?” [p. 176] , while the author, just a few pages later [p. 185], admires the life of a friend in Zanzibar, stating, “One could definitely envy the family’s way of life. They ‘lived’ life on a farm…” In this fascinating story about a modern young man’s attempts to share an endangered life style, Stephenson may raise more questions than he answers.

Notes: The author’s photo appears on http://www.tribalmania.com

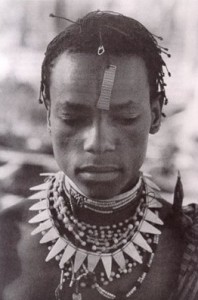

The photo of the young Hadzabe man comes from the Amazon product page: http://www.amazon.com/