“There were twenty of us in my barracks…twenty boys. And only two came back. One who went mad, and myself. But that doesn’t mean we survived [the war]. I don’t think I did survive it. I may not be buried in a French field but I linger there. My spirit does, anyway…There’s a difference between breathing and being alive.”—Tristan Sadler

Although a major part of The Absolutist centers on the horrors of World War I, Irish author John Boyne has created a novel which goes beyond the typical “war story” and becomes also a study of character and values. This broader scope allows the novel to appeal to a wider audience interested in seeing the effects of war on the main character, Tristan Sadler, throughout the rest of his life. More a popular novel than a “literary” novel in its appeal to the reader, Boyne has carefully constructed the plot with alternating time settings – before, during, and after the war – to take full advantage of the elements of surprise. The author often hints at personal catastrophes or dramatic events in one part of the novel, creating a sense of suspense and foreboding, then reveals these secret events in grand fashion in another part, keeping the pace so lively that it is difficult for the reader to find a place to stop.

Although a major part of The Absolutist centers on the horrors of World War I, Irish author John Boyne has created a novel which goes beyond the typical “war story” and becomes also a study of character and values. This broader scope allows the novel to appeal to a wider audience interested in seeing the effects of war on the main character, Tristan Sadler, throughout the rest of his life. More a popular novel than a “literary” novel in its appeal to the reader, Boyne has carefully constructed the plot with alternating time settings – before, during, and after the war – to take full advantage of the elements of surprise. The author often hints at personal catastrophes or dramatic events in one part of the novel, creating a sense of suspense and foreboding, then reveals these secret events in grand fashion in another part, keeping the pace so lively that it is difficult for the reader to find a place to stop.

The novel begins with Tristan Sadler, now twenty, arriving in Norwich, England, on an undescribed personal mission. The war has been over for nine months, but Tristan still has many issues to resolve, among them nervousness and stress-related trembling, particularly of his right hand and index finger. Though he “hasn’t been well” for the past three years, he leaves London for this meeting in Norwich, only to find upon his late arrival that his room in a lodging house is not ready. To pass the time until the room is cleaned, Tristan walks around the town, reminiscing about his past, and in so doing, sets up some of the themes and symbols that pervade the novel.

Norwich Castle

He circles Norwich Castle, but does not go inside: “Castles such as this, after all, were nothing more than the remains of military bases where soldiers might camp out and wait for the enemy to appear. I did not need to see any more of that.” Though he is an agnostic, he goes inside Norwich Cathedral, “not so much for [the] religious aspect – but for the peace and tranquility it offered within.” Most importantly, on leaving the cathedral, he sees the bust and the grave of Edith Cavell, “our great nurse patriot, who had helped hundreds of British prisoners of war escape from Belgium,” only to be captured in 1915, tried by the Germans, executed by firing squad, and ultimately declared a heroine and a martyr. Tristan feels “a great sense of joy at discovering her grave.”

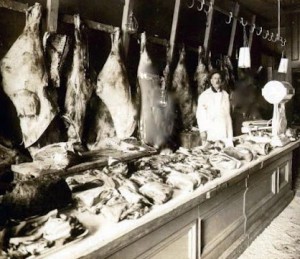

A butcher shop, similar to the one belonging to Tristan’s father, complete with sawdust on the floor, is a symbol paralleliing the carnage of war.

Flashing back three years, the author then presents Tristan as a seventeen-year-old who has been thrown out of home and family. Having refused to join his father in the family butchery, he lies about his age and volunteers for war. With no one who cares whether he is alive or dead, he trains as a soldier at Aldershot under Sgt. James Clayton, a sadistic leader, totally committed to the war and to the killing. After ten weeks’ training, his group of twenty men is transported to France. Among his few friends in the trenches is Will Bancroft, the son of Rev. Bancroft, vicar of the cathedral in Norwich.

Norwich Cathedral

When Will dies in France, something we know from the opening pages, Tristan writes to Will’s sister Marion, arranging to go to Norfolk to return all the letters she wrote to Will while he was overseas. Once he has arrived, however, Tristan is unsure whether he has done the right thing. Marion is tense and quarrelsome, and wants him to talk with her parents. Tristan, nervous to start with, is terrified. “Why did I come here?,” he asks himself. “What was I thinking? If it was redemption I sought, there was none to be found. If it was understanding, there was no one who could offer it. If it was forgiveness, I deserved none.” More mysteries are suggested at the meeting with the parents.

Bust of Edith Cavell

As the action of the novel moves back and forth between Tristan’s actions in Norfolk in June, 1919, and in France between July and September, 1916, the author creates suspense by having the characters in 1919 refer to events from 1916 which the author has not yet introduced, leaving the reader to wonder what new mysteries underlie Tristan’s visit. Some of these mysteries also revolve upon Tristan’s memories of his own childhood, some of which connect with what happens in France. Two characters in his group in France prove to be conscientious objectors, one of them still waiting for his approval from the army. These characters, who discuss their beliefs with Tristan, are sometimes assigned to be as stretcher-bearers, one of the most dangerous jobs of all, since they are exposed to German bullets the minute they leave the trenches. Many of them die, but they have dared to challenge the “moral absolute” of war and do not fire their guns, preferring the moral absolute of peace. Tristan challenges nothing, hoping only to survive so he can return to real life.

Grave, Edith Cavell, Norwich Cathedral

Though author Boyne provides plot twists galore, the pattern of the plot structure itself becomes a bit predictable after awhile, with constant unexplained references leading to mysteries which are then reconciled to reveal important information. At times, the reader may feel manipulated, his/her feelings held captive by the author until the time arrives to reveal another surprise. Any big questions about character arise from information withheld, rather than, more subtly, from contradictory information which the reader acquires from observing a character’s long-term behavior and then reconciles for him/herself based on the characters’ continuing actions. In fact, the first “surprise” of the novel is one that most readers will guess almost immediately. Tristan’s appearance in the conclusion as an eighty-year-old man, brings his life (and the author’s themes) up to date, as he reviews his decisions and behavior, but it also feels contrived.

The novel propels itself with exciting scenes while also presenting thoughtful contrasts between “absolutists” totally dedicated to a point of view which will allow for no compromise, and those who see compromise as essential to survival. The many thematic symbols (Tristan refusing to work in the family butcher shop but enlisting in the army, Edith Cavell vs. Tristan in ideology, and a conscientious objector vs. Sgt. Clayton) provide reminders of the dangers and difficulties that can arise whenever these issues become questions of morality or theology. Though the novel is very serious, with no humor to leaven it, The Absolutist is riveting, and a fast read.

ALSO by John Boyne: THIS HOUSE IS HAUNTED, A LADDER TO THE SKY

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Murdo Macleod is from http://www.guardian.co.uk

Norwich Castle appears here: http://www.yourvillage.flyer.co.uk

A butcher shop, similar to the one belonging to Tristan’s father, complete with sawdust on the floor, is from http://kindredfootprints.blogspot.com, a symbol which parallels the carnage of war.

Norwich Cathedral is from http://www.art-history-images.com

The bust of Edith Cavell, an absolutist who saved hundreds of soldiers in Belgium and was martyred for her work and beliefs, is on a monument at Norwich Cathedral: http://www.oldcity.org.uk More information about Edith Cavell appears on this site.

The grave of Edith Cavell at Norwich Cathedral: http://gallery.nen.gov.uk

ARC: Other Press