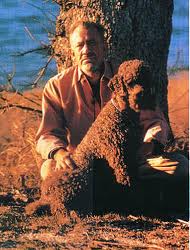

“I took one companion on my journey – an old French gentleman poodle known as Charley. Actually his name is Charles le Chien. He was born in Bercy on the outskirts of Paris and trained in France, and while he knows a little poodle-English, he responds quickly only to commands in French. Otherwise he has to translate, and that slows him down. He is a very big poodle, of a color called bleu, and he is blue when he is clean.”

When J ohn Steinbeck obeys a life-long urge to drive from coast to coast in 1960, he little anticipates the variety of the “American experience.” Beginning in Maine and traveling along the northern states through Wisconsin, the Badlands, Montana, and all places in between, to Washington and Oregon, Steinbeck then decides to visit his childhood community of Salinas, in northern California. After meeting with friends there, though many have died, he then drives southward through the length of California and then eastward through the southwest desert to Texas, Louisiana, and eventually up to Virginia before returning to New York.

ohn Steinbeck obeys a life-long urge to drive from coast to coast in 1960, he little anticipates the variety of the “American experience.” Beginning in Maine and traveling along the northern states through Wisconsin, the Badlands, Montana, and all places in between, to Washington and Oregon, Steinbeck then decides to visit his childhood community of Salinas, in northern California. After meeting with friends there, though many have died, he then drives southward through the length of California and then eastward through the southwest desert to Texas, Louisiana, and eventually up to Virginia before returning to New York.

Carrying the reader along with him as he reconstructs this journey for publication in 1962, Steinbeck observes people and human nature, being careful not to draw conclusions about an entire area based on the individuals he meets along the way. Often it is their reactions to Charley, his aging blue poodle, which stimulate their conversations and allow Steinbeck glimpses of their thinking and ways of life. From the terminally gloomy waitress in Maine to the evil-looking mechanic in Oregon (who turns out to be the kindest and most generous of men), Steinbeck explores attitudes toward life (and strangers). Steinbeck’s high school buddy (who almost comes to blows with him) shows him that you really can’t go home again, and “the cheerleaders” of New Orleans, a group of white-supremacist women who taunt and scream obscenities at a tiny black girl integrating one of their schools, shows him how much work the human race still has left to do.

and ways of life. From the terminally gloomy waitress in Maine to the evil-looking mechanic in Oregon (who turns out to be the kindest and most generous of men), Steinbeck explores attitudes toward life (and strangers). Steinbeck’s high school buddy (who almost comes to blows with him) shows him that you really can’t go home again, and “the cheerleaders” of New Orleans, a group of white-supremacist women who taunt and scream obscenities at a tiny black girl integrating one of their schools, shows him how much work the human race still has left to do.

As he travels in his truck with a house attached to its bed (a pre-Class C camper invention that he calls “Rocinante” after the horse of Don Quixote), he notes the changing landscape, the disappearance of treasured aspects of the environment, and the growth of new trends–including the increasing popularity of the mobile home and the contemporary loss of “roots.” He is genuinely frightened by the Badlands, until night falls, when it becomes beautiful. He adores Montana, and he hurries through the almost blank southwestern desert where he learns something new about shooting. Though Steinbeck gets tired of travel before the end of the trip, he still manages to record signal moments which resonate with the reader.

What elevates this book especially is the glimpses it gives of Steinbeck himself, a far more upbeat man than one would expect from the California novels like Cannery Row, Of Mice and Men, and The Grapes of Wrath. His observations of life in the early 1960s capture the country at pivotal moments of history–the time of Sen. John Kennedy and freedom rides. In this respect, Steinbeck creates a time capsule for future generations and a picture of himself that lovers of his writing will treasure.

Notes: The photo of Steinbeck and Charley appears on the cover of an early edition of Travels with Charley.

The photo of Rocinante, the trailer in which Steinbeck and Charley traveled the country, appears on http://as.sjsu.edu/

Also reviewed here: THE MOON IS DOWN, OF MICE AND MEN