“If I could just chug twenty beers and then go to sleep, they’d find my cold body the next day. It was the only death a screw-up like me deserved. The law of life states that he who cannot rise should make way for others. The world’s small and useless people are better off underground where they can’t be heard, awaiting the last judgment. That’s the day we’ll all be equal.”

Thoug h Mario Alvarez, in Juan de Recacoechea’s novel American Visa, likes to think of himself as a hero created by one of the great writers of hard-boiled crime stories, he recognizes that, in reality, he is something of a romantic, “a lover of the impossible, a dreamer who never can choose his dream, an incomplete man.” He has come from Oruro to La Paz, Bolivia, to get a tourist visa for the United States, and he has only enough money for a week’s stay at the Hotel California, a seedy hotel in which his room is like “a cell for a Trappist monk.” While he’s awaiting his interview with U.S. officials, he comes to know some of the other inhabitants of the hotel, all of them with their own problems. Don Antonio Alcorta is an elderly asthmatic who, though dependent on handouts, is a person “without visible frustrations.” Senor Antelo is a gigantic former soccer goalie who is hoping to get a job in the Customs Department, where his life will be secure. Alfonso, “or Gardenia, depending on circumstances,” is a transvestite heavily involved in the gay bar scene. Mario also visits with his uncle, a barber who does not recognize him, and he spends time with Blanca, a prostitute who wants him to be her pimp.

h Mario Alvarez, in Juan de Recacoechea’s novel American Visa, likes to think of himself as a hero created by one of the great writers of hard-boiled crime stories, he recognizes that, in reality, he is something of a romantic, “a lover of the impossible, a dreamer who never can choose his dream, an incomplete man.” He has come from Oruro to La Paz, Bolivia, to get a tourist visa for the United States, and he has only enough money for a week’s stay at the Hotel California, a seedy hotel in which his room is like “a cell for a Trappist monk.” While he’s awaiting his interview with U.S. officials, he comes to know some of the other inhabitants of the hotel, all of them with their own problems. Don Antonio Alcorta is an elderly asthmatic who, though dependent on handouts, is a person “without visible frustrations.” Senor Antelo is a gigantic former soccer goalie who is hoping to get a job in the Customs Department, where his life will be secure. Alfonso, “or Gardenia, depending on circumstances,” is a transvestite heavily involved in the gay bar scene. Mario also visits with his uncle, a barber who does not recognize him, and he spends time with Blanca, a prostitute who wants him to be her pimp.

Mario has all the papers he needs for his visa—a paper saying that he is a former teacher and the founder of the dance group Diablada Autentica; a bank statement saying that he has 5000 pesos on deposit; and a contract of sale for a house in Oruro, a three-story mansion worth $70,000, registered at City Hall. When he hears that the consulate will actually need to verify his documents and may even use detectives in their investigation, however, he flees the consulate–knowing that “if they deny you once, they’ve denied you forever.” Learning from an acquaintance that the owner of a travel agency can speed up the visa process for $800, since the agent knows people who work in the visa business, Mario is determined that somehow he will find the money to ensure that he gets his visa.

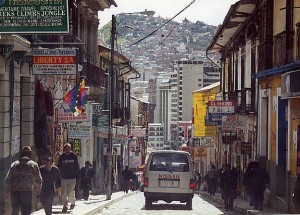

While he is trying to get the  money he needs, the reader learns Mario’s family history and follows him as he wanders La Paz, a city which has changed dramatically in recent years with the arrival of half a million peasants, many of them Indian. He meets a former friend from the army, now a miner, who is part of a protest that has been going on for a week—a protest in which the miners have crucified themselves on a public fence. He meets an author at a book-signing, along with a beautiful and wealthy woman. He attends an elegant party, and he spends nights getting drunk in the sleaziest bars in the city. By the time he finally decides what he must do to get the money he needs, the reader is rooting for his success, even as he is showing himself to be an undesirable candidate for a visa.

money he needs, the reader learns Mario’s family history and follows him as he wanders La Paz, a city which has changed dramatically in recent years with the arrival of half a million peasants, many of them Indian. He meets a former friend from the army, now a miner, who is part of a protest that has been going on for a week—a protest in which the miners have crucified themselves on a public fence. He meets an author at a book-signing, along with a beautiful and wealthy woman. He attends an elegant party, and he spends nights getting drunk in the sleaziest bars in the city. By the time he finally decides what he must do to get the money he needs, the reader is rooting for his success, even as he is showing himself to be an undesirable candidate for a visa.

All of the characters here are repellent in some way, and though author Juan de Recacoechea presents them somewhat sympathetically, he does not present them romantically. His style is naturalistic, filled with unique metaphors and similes. Most of the characters are helpless, in the grip of outside forces which are controlling their lives, and all of them have “flexible” ideas of what constitutes right and wrong. Most of them, however, cannot afford the “luxury” of honesty if they want to move beyond the poverty which engulfs them. Life here is truly absurd—a kind of farce–and Mario himself knows that only by committing a major crime “can I redeem myself in my own eyes.”

kind of farce–and Mario himself knows that only by committing a major crime “can I redeem myself in my own eyes.”

“Local color” in this novel is dark and filled with misery, and as the action evolves and incorporates all levels of society, the sense of dramatic irony increases. Described as “picaresque noir” by Amherst Prof. Ilan Stavins in the Afterword, the novel has elements of the hard-boiled style of the great mystery writers of the 1930s and 1940s, but it is also noticeably existentialistic, reminiscent of both Kafka and Sartre in the sense of amorality, absurdity, and hopelessness. The author differs from the existentialists in that his characters seem to accept their ultimate fates with a kind of dark humor which moderates their despair, the expectation that “of course” this is the way things will end, and “of course” this is the way it should be. They manage to find elements of pleasure under even the nastiest circumstances, and they have learned to accept life as it is— but only if they cannot change it to their advantage. Published in Spanish in 1994, this novel is reputed to be one of fewer than a dozen novels from Bolivia to have been translated into English–in this case, by Adrian Althoff in 1997.

Notes: Also reviewed here: de Recacoechea’s ANDEAN EXPRESS

The author’s photo by Caitlin Esch and an outstanding interview appear in http://www.brooklynrail.org

The La Paz street and other photos may be seen at http://www.caminandosinrumbo.com

This novel was made into a film in 2006. The poster and the trailer for it appear on http://www.imdb.com The book does not feel as frantic as the film trailer does.