“A strong positive response to [Edward] Hopper’s paintings is by no means uncommon, in America and throughout the world. But I’ve come to believe that it’s singularly strong among readers and writers…those of us who care deeply for stories…It’s not because of the stories his paintings tell….[They] don’t tell stories…They suggest – powerfully, irresistibly – that there are stories within them, waiting to be told…It’s our task to find [them] for ourselves.” – Lawrence Block, editor/writer for this collection.

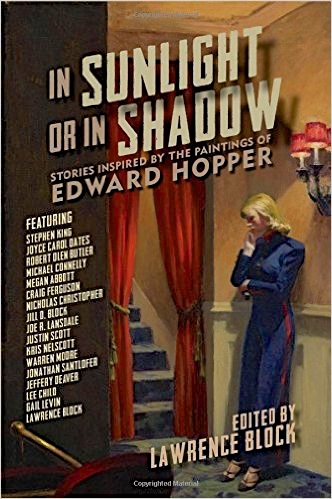

In a book that will delight lovers of stories and art, Lawrence Block, editor and writer, presents stories written by himself and sixteen other authors in response to seventeen paintings by American artist Edward Hopper (1882 – 1967). Most of Hopper’s paintings are quiet, with little, if any, action and few, if any, characters. The overall mood for most of Hopper’s paintings is bleak, and his characters appear to be lonely, immersed in their own thoughts, and alienated from society. Though Hopper specializes in the play of sunlight and shadow (hence, the title of the book), he does so with dramatic effect, and most of his major paintings show isolated characters dealing with the darkness, the light being just beyond them. All of the seventeen writers who have contributed a short story to illustrate a Hopper painting clearly catch the mood of depression and withdrawal which seems to characterize so many of these paintings, and anyone familiar with the work of these writers, most of whom are mystery writers, should also know what to expect: Only two writers create stories that can be said to have even slightly “happy” endings, and one of those occurs on a deathbed.

In a book that will delight lovers of stories and art, Lawrence Block, editor and writer, presents stories written by himself and sixteen other authors in response to seventeen paintings by American artist Edward Hopper (1882 – 1967). Most of Hopper’s paintings are quiet, with little, if any, action and few, if any, characters. The overall mood for most of Hopper’s paintings is bleak, and his characters appear to be lonely, immersed in their own thoughts, and alienated from society. Though Hopper specializes in the play of sunlight and shadow (hence, the title of the book), he does so with dramatic effect, and most of his major paintings show isolated characters dealing with the darkness, the light being just beyond them. All of the seventeen writers who have contributed a short story to illustrate a Hopper painting clearly catch the mood of depression and withdrawal which seems to characterize so many of these paintings, and anyone familiar with the work of these writers, most of whom are mystery writers, should also know what to expect: Only two writers create stories that can be said to have even slightly “happy” endings, and one of those occurs on a deathbed.

Most of the stories involve murders, the contemplation of murder, or other crimes. Robert Olen Butler, Lee Child, Michael Connelly, Jeffery Deaver, Stephen King, and Lawrence Block, among others, are well known for the dark views of life they show in their fiction and have long careers in detailing the crimes that isolation can spawn. Even Joyce Carol Oates, not a mystery writer, creates a dark story of a woman waiting for a lover who is late and the unhealthy thoughts that go through her mind as she waits with scissors hidden under the cushion of her chair. And though the plots paired with these paintings differ widely in their details, the darkness prevails throughout all, creating a perfect melding of paintings with the authors who use them as inspiration for their stories.

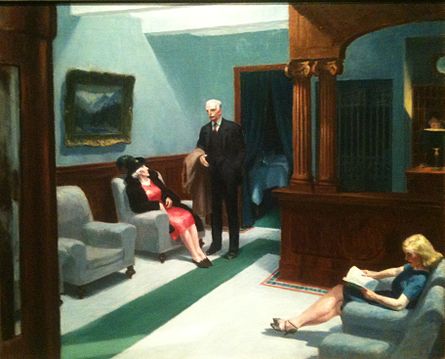

“Soir Bleu,” an early painting (1914) with seven characters sitting around an outdoor table in France, by far the greatest number of characters seen in any Hopper painting, inspires Robert Olen Butler to tell a story in which an artist, Vachon, is hoping to sell one or more paintings to a person he sits with at the table. The prostitute standing beside the table, whom he knows, wants to help him. Also sitting at the table is Pierrot, the clown, whom Vachon believes he has seen many years before, a twist which brings about a dramatic conclusion. In “The Truth About What Happened,” a clever story by Lee Child, featuring the 1943 painting “Hotel Lobby,” the main character is an FBI special agent working undercover on security for the Manhattan Project. His boss, a “Mr. Hopper,” is directing him as he investigates an elderly man who works for the project to see if he could be blackmailed by the enemy. In a humorous touch, Hopper and the agent decide to set up a meeting with the old man, a kind of intervention, using a hotel lobby at night, one identical to that of the painting.

Stephen King’s “The Music Room,” inspired by Hopper’s “Room in New York,” 1932, features a painting in which Mr. Enderby, a formally dressed man, minus a jacket, is reading the newspaper at a table, while his bored wife is playing the piano, one-fingered, a seemingly harmless couple and setting. Gradually, the reader realizes that something is amiss, and as Enderby concentrates on the newspaper and discusses what is happening in the various comic strips in the paper, Mrs. Enderby begins to play popular music on the piano. Soon Stephen King’s trademark dark wit appears, with details I will forever remember whenever I see this painting. In Michael Connelly’s “Nighthawks,” based on Hopper’s most famous painting of the same name, his famed private detective Bosch meets a young woman at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she is studying and taking notes on the Hopper painting. Bosch has been hired by a movie producer, his client, to find a young woman who ran away eight years ago. As always, Bosch stays true to himself and to what it right but at the cost of feeling like a man sitting alone at the café counter with the other nighthawks.

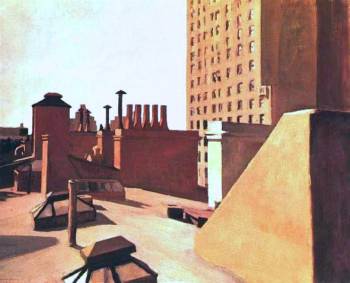

One of the most interesting stories comes from Gail Levin, whose credentials as the foremost expert on Edward Hopper are unparalleled. From 1976 – 1984, she was curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, where she created landmark exhibitions of the world of Edward Hopper. She has also written several books and many articles on his work. In “The Preacher Collects,” her first published piece of fiction, she is inspired by the painting “City Roofs,” 1932, a painting of light and shadow – and no people. Writing from the point of view of Arthayer R. Sanborn, said to be a graduate of Gordon College in Wenham, Massachusetts, and Andover Newton Theological Seminary in Newton, Levin creates a character who is said to have served in Baptist churches in Massachusetts and Rhode Island before going to Nyack, New York, the town where Edward Hopper grew up, and where his family remained when he claimed New York City as his home. There Sanborn meets Marion Louise Hopper, only sibling of Edward Hopper. When the elderly Marion becomes ill, Edward comes back reluctantly to help her out, and his wife Jo stays for a while, but ultimately Marion becomes increasingly dependent on the church and its preacher. Levin’s depiction of the relationships between Hopper and his wife and between Hopper and his sister are fascinating in this story, but what becomes overwhelmingly clear is that during Marion’s illness and after Hopper’s death, Hopper’s estate is plundered. Here the details are so specific it is difficult to imagine that they are not true, but this is fiction, and how much is really true and how much is invented remains to be discovered. For anyone who loves stories and art, especially that of Edward Hopper, this book will provide more hours of fun than anything you may have read in ages.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://threeroomspress.com/authors/darkcitylights/

Lee Child’s story, “The Truth about What Happened,” was inspired by Hopper’s “Hotel Lobby,” 1943. https://en.wikipedia.org/

Stephen King’s “The Music Room,” evolved from Hopper’s “Room in New York,” 1932. http://www.sheldonartmuseum.org

Gail Levin’s “The Preacher Collects,” took its inspiration from Hopper’s “City Roofs,” 1932. https://brunch.co.kr

Michael Connelly’s “Night Hawks,” was inspired by Hopper’s most famous painting of the same name from 1942. https://en.wikipedia.org/