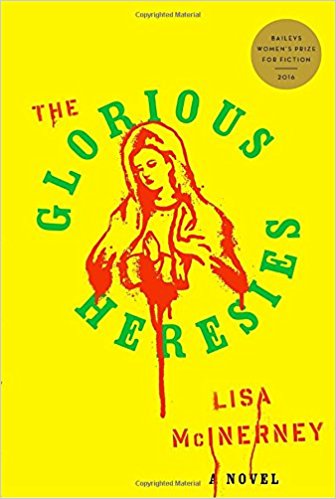

Note: This novel was WINNER of the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction, 2016, and WINNER of the Desmond Eliot Prize for best debut novel published that year in the UK.

“Look, Father. There are a lot of things I’m sorry for…it feels like I’ve been sorry all my life. First I was supposed to be sorry for having a child out of wedlock….I went away to have the baby and then I gave him up as my penance… Your kind had my mother and father’s ears; I didn’t stand a chance. So if many, many years later my son has found me and brought me home, only he has turned into a thug and my hands are so shaky I accidentally kill fellas, don’t the amends I’ve already made mean anything to the Man Above?”—Maureen Phelan to priest in Confession.

The prose of Irish debut novelist Lisa McInerney is so musical that even the horrors of characters living barebones existences in the drug-infested underworld of Cork begin to feel engaging. Here McInerney creates families and friends, enemies and predators, and lovers and their betrayers as they all try to survive the forces working against them. Their possibilities of flourishing within this fraught atmosphere are practically nil. Many characters use drugs and alcohol to make their lives more bearable, and most still have hope for a future in which they can find some level of happiness. These characters come to life – and in some cases, death – within a society which exists on its own terms, a dark society outside the dominantly Catholic mainstream, with its own rules about what is right, what is tolerated, and what requires repentance and/or punishment. Many of McInerney’s characters are aware of the ironies in their lives, as Maureen Phelan’s confession to a priest at the beginning of this review reveals, and her intentional humor in places throughout the novel provides respite for readers who might begin to weary of the sad, inner battles her characters face.

The prose of Irish debut novelist Lisa McInerney is so musical that even the horrors of characters living barebones existences in the drug-infested underworld of Cork begin to feel engaging. Here McInerney creates families and friends, enemies and predators, and lovers and their betrayers as they all try to survive the forces working against them. Their possibilities of flourishing within this fraught atmosphere are practically nil. Many characters use drugs and alcohol to make their lives more bearable, and most still have hope for a future in which they can find some level of happiness. These characters come to life – and in some cases, death – within a society which exists on its own terms, a dark society outside the dominantly Catholic mainstream, with its own rules about what is right, what is tolerated, and what requires repentance and/or punishment. Many of McInerney’s characters are aware of the ironies in their lives, as Maureen Phelan’s confession to a priest at the beginning of this review reveals, and her intentional humor in places throughout the novel provides respite for readers who might begin to weary of the sad, inner battles her characters face.

The first part of the novel establishes the several different stories which will develop and overlap within the action, starting with a teenage love story which develops throughout the novel and unites some of McInerney’s plot lines and themes. Fifteen-year-old Ryan Cusack, being brought up by his alcoholic father, finds himself receiving the attentions of classmate Karine D’Arcy, someone who has been in school with him for three years. They believe they are meant for each other and that they are in love. A few paragraphs later, a new character, Maureen Phelan, a fifty-nine-year-old “slip of a whip,” has just killed an intruder at her apartment, something that she does not think much about – after all, he was an intruder – but the murder was messy, and she wants help getting her floor cleaned. Telephoning her son Jimmy, described quickly by the author as someone who “sells fags and dope and cans of lager,” and who has also killed cops, she demands that he replace her floor and remove the body, a job he arranges quickly.

The first part of the novel establishes the several different stories which will develop and overlap within the action, starting with a teenage love story which develops throughout the novel and unites some of McInerney’s plot lines and themes. Fifteen-year-old Ryan Cusack, being brought up by his alcoholic father, finds himself receiving the attentions of classmate Karine D’Arcy, someone who has been in school with him for three years. They believe they are meant for each other and that they are in love. A few paragraphs later, a new character, Maureen Phelan, a fifty-nine-year-old “slip of a whip,” has just killed an intruder at her apartment, something that she does not think much about – after all, he was an intruder – but the murder was messy, and she wants help getting her floor cleaned. Telephoning her son Jimmy, described quickly by the author as someone who “sells fags and dope and cans of lager,” and who has also killed cops, she demands that he replace her floor and remove the body, a job he arranges quickly.

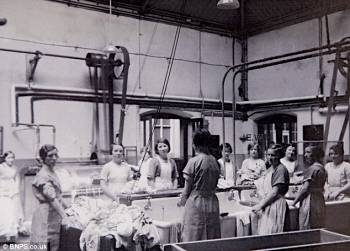

Pregnant unmarried girls, like Maureen, in her day, were often assigned to the Magdalen Laundries, places where they could work doing laundry for the county, have their babies, and then put them up for adoption.

New characters enter the narrative to set up further action. Georgie, who ran away from home at fifteen, loved Robbie O’Donovan for six years, but the relationship eventually soured and he has now left her. Alone, and with no future, she has become a prostitute with a bad drug habit. In another shift of the story line, the person hired to fix Maureen Phelan’s blood-soaked floor is Tony Cusack, father of fifteen-year-old Ryan. Tony recognizes the person killed in Maureen’s house, a situation which could lead to problems if crime boss Jimmy Phelan were to learn that Tony knows who the victim is. As these story lines begin to interconnect and switch back and forth among the characters, their inner thoughts are revealed. All have goals but are also frustrated by both outside circumstances and circumstances of their own making. For some characters, it is too late to reach their goals; for young Ryan Cusack, there may be hope. Though Ryan’s father seems intent on ruining Ryan’s life, the school headmaster wants to help him. Rapidly changing and alternating scenes draw the characters together, and carefully spaced short “interludes” throughout keep the reader abreast of events as they happen in the relationship between Ryan and Karine as the rest of the novel is unfolding on a grander scale.

The author’s focus on developing scenes which convey characters in all their flaws and foibles through lively dialogue and action makes this novel of relationships far more than the melodrama it might have been. Themes of right and wrong coincide with the ideas of sin and redemption through punishment and atonement for some characters like Maureen Phelan. Civil law, Catholic religious law, Christianity at its loving heart, and the intentions and the rules of institutions run by well-meaning, do-gooders overlap throughout. Part II of the novel concerns itself with some of these overlaps as seen in the various rehabilitation facilities to which some characters are sent while others end up in St. Patrick’s Institution, a violent jail run by the state. Still others decide to take justice into their own hands, with dire results. Throughout, Maureen Phelan keeps the reader smiling at her uninhibited behavior and attitudes, even as that behavior often horrifies. The novel develops further in new sections, and as time passes and the characters’ lives are brought up to date over the course of three years, the reader sees the complexity of all these issues.

Another character goes to detox in the countryside, a place run by well-meaning evangelicals.

As Lisa McInerney shows in this involving and thematically complex novel, the economic problems in Ireland, the well-publicized complications created by the sexual crimes of the clergy, and the resulting decline of the church’s influence have left swathes of needy people with few personal or social resources. Her ardent and uninhibited approach to her narrative makes the reader more dramatically aware of the inner conflicts faced by these ordinary people as their social supports disappear and their religious supports are shown to be flawed. Yet McInerney’s picture of Ireland, specifically Cork, is so full of energy – and toughness – that one must believe that Maureen Phelan, for all her craziness, is closer to being honest and good than the clergyman to whom she is confessing. As she recalls her unwed pregnancy, she asserts, “I was lucky, Father. I was only sent away. A decade earlier and where would I have been? I might have died in your asylums, me with the smart mouth. I killed one man but you would have killed me in the name of your god, wouldn’t you? How many did you kill? How many lives did you destroy with your morality and your Seal of Confession and your lies?…I know I’m sorry. What about you?”

Yet another character keeps a scapular nearby, reminding herself that “Whosoever dies wearing this scapular shall not suffer eternal fire.”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is found on http://www.ourdailyread.com/

The Magdalen Laundries were an option for Maureen Phelan, in her day, a place for pregnant, unmarried girls where they worked for the county doing laundry, while awaiting the birth of their babies, which were then put up for adoption. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/

The cruel St. Patrick’s Institution, recently closed, was another place where another character here spends nine months. http://www.thejournal.ie/

Detox facilities, sought by yet another character, were often run by evangelical Christians in the countryside, where there was no real escape. https://www.imagine.ie/

A scapular, sometimes worn by devout Christians, reminds the wearer that redemption is possible, even for the worst of sinners. One character here keeps one at her side all the time. https://www.catholiccompany.com/