“Biedermann’s good fortune does not waver much, however the destinies of others are jarred and twisted as God sees fit to do so often. And if such blessings result from our staunch neighbor’s close attention to his land and animals, why, then, those of us who labor no less strenuously have cause to ponder how even-handedly the destinies of men on Earth are administered from on High, and to ask in a whisper behind closed doors, whether some are not being dealt a shorter hand than others.”

When  homesteader Leo Biedermann arrives in the plains of South Dakota in January,1882, during the most severe weather the area has seen in years, he immediately sets about building his house and barn, stocking the farm with cattle and horses, and planning his crops. The other homesteaders are astonished at his fortitude in the face of blizzards and bitterly cold weather, and though he is not friendly, they help him out when he needs machinery or a helping hand, and wish him well. When the first crops are harvested at the end of Biedermann’s first summer, Biedermann has managed to bring in the largest crop of all.

homesteader Leo Biedermann arrives in the plains of South Dakota in January,1882, during the most severe weather the area has seen in years, he immediately sets about building his house and barn, stocking the farm with cattle and horses, and planning his crops. The other homesteaders are astonished at his fortitude in the face of blizzards and bitterly cold weather, and though he is not friendly, they help him out when he needs machinery or a helping hand, and wish him well. When the first crops are harvested at the end of Biedermann’s first summer, Biedermann has managed to bring in the largest crop of all.

Told through the journal of Gerhardt Praeger, a long-term settler with seven sons to help him on his farm, the narrative of Biedermann and his relationships with the other homesteaders unfolds. Biedermann is a difficult man who travels with two ferocious dogs, and Praeger’s first meeting with him has not been ideal. The dogs attack Praeger’s horse, which rears and unseats him, leaving him slightly injured—and less than enthusiastic, though still hospitable, toward his neighbor. Over the course of five years, Biedermann manages to prosper, through drought (during which he miraculously finds water on his property), floods which manage to spare most of his fields, blizzards, and plagues of grasshoppers which bypass his land. Every other homesteader is devastated.

In many ways a morality tale, this brutally realistic picture of life on the plains honors the strength and stamina of the homesteaders in the face of terrible trials, their lives lived constantly on the edge of disaster, but it is also a tribute to the values of these men and women, who share whatever they have during difficult times, who help each other, who have faith in a higher power, and who never give up hope. Biedermann’s success cannot help but raise eyebrows, and it does stir some secretly held feelings of jealousy, but these men and women are busy tending to their own farms.

Though the community may ask themselves “Why Biedermann? Why not us?,” they have little time to contemplate deep philosophical truths, continuing to have faith and blaming their own pride for their lack of success. For Praeger, who shares his feelings with the reader, the success of Bie dermann is particularly bitter, since Praeger has helped Biedermann, has allowed his young twins to work for him, has provided him with needed equipment, and has been a good neighbor, and he must constantly remind himself to have faith, even when Biedermann’s success seems undeserved.

dermann is particularly bitter, since Praeger has helped Biedermann, has allowed his young twins to work for him, has provided him with needed equipment, and has been a good neighbor, and he must constantly remind himself to have faith, even when Biedermann’s success seems undeserved.

Praeger’s narrative achieves excitement through the alternation of Praeger’s journal with Interleaves reflecting other points of view and describing past history and present challenges—Praeger’s family background and his reasons for coming to South Dakota from Wisconsin, Biedermann’s relations with his father and his attraction to the Widow Jenssen, the outbreak of a prairie fire at Schneider’s place, various climatic disasters, and ultimately, “harsh words” between Biedermann and Praeger’s son Harris, which leads to the climax. These words occur, symbolically, during a period of  “overheated wind” and drought, during which Biedermann “does more than well,” while everyone else loses nearly everything. Harris Praeger is short-tempered and surly, and his strawberry birthmark is often regarded as the touch of the devil. Even his father is powerless to prevent Harris’s ultimate actions against Biedermann.

“overheated wind” and drought, during which Biedermann “does more than well,” while everyone else loses nearly everything. Harris Praeger is short-tempered and surly, and his strawberry birthmark is often regarded as the touch of the devil. Even his father is powerless to prevent Harris’s ultimate actions against Biedermann.

Though the title can be considered in its literal sense—the dramatic crises which occur on the plains, including prairie fires, blizzards, and bitter cold–it is also symbolic of the extremes of temperament which one sees between the fiery Harris and the icy Biedermann. Religious symbols also pervade the novel—the fires of hell, miracles and the lack of miracles, pride as the cardinal sin, and even the image of a solitary wanderer in the wilderness. For the homesteaders, religion is as much a part of reality as the sun and the rain, and this symbolism complements author Lloyd Zimpel’s crystalline prose and the vibrant reality of the setting.

First published in 2006, this novel already feels like a classic, with its elegant and formal prose, its universal themes, its focus on a unique time and place, its broad vision of humanity with all its glories and faults, and its lack of artifice and sentimentality. Life is often harsh, but nowhere is life harsher than here in the lives of these Dakota homesteaders. (On my Favorites list for 2007)

Notes: The author’s photo appears on his Author Page at Unbridled Books: http://unbridledbooks.com

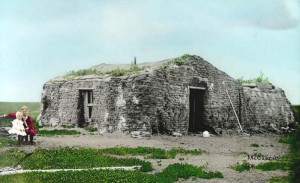

A sod house, ca. 1903, in North Dakota, with two children outside: http://www.americaslibrary.gov

A prairie fire is shown on http://lucascountyhistoricalsociety.blogspot.com/

Swarm of grasshoppers: http://worldsofimagination.com