Note: This novel was WINNER of the Welsh Language Book of the Year Prize in 2007. Author Llwyd Owen did the English translation himself.

“Everything and everyone I ever had has gone up in smoke, but at least I’ve got someone with me in this strange world, even if I can wave my hand through him as easily as clearing fag air. He doesn’t cramp my style like some second shadow; in fact, there he goes now, disappearing into the ether like an odourless fart.”—Alun Brady, in prison.

An unusual and often dark novel, Faith, Hope & Love is billed as an urban thriller, but it is far more the psychological study of an unusual anti-hero than it is a mystery. In fact, the biggest mystery of the book is why the main character is in prison in the first place, a question which does not get answered until late in the novel. The Prologue, entitled “The Beginning of the End,” raises additional questions concerning a car crash, which is described there, and the identities of the people in the car—again, issues which are not addressed again till late in the novel. In between the Prologue and the resolution of these questions, however, the novel is study of Alun Brady and his family, much more a sensitive domestic drama than an action thriller, a study of identity and reality—personal, familial, cultural, and religious—as revealed through a series of unrelenting ironies in which God, fate, and free will do battle.

unusual and often dark novel, Faith, Hope & Love is billed as an urban thriller, but it is far more the psychological study of an unusual anti-hero than it is a mystery. In fact, the biggest mystery of the book is why the main character is in prison in the first place, a question which does not get answered until late in the novel. The Prologue, entitled “The Beginning of the End,” raises additional questions concerning a car crash, which is described there, and the identities of the people in the car—again, issues which are not addressed again till late in the novel. In between the Prologue and the resolution of these questions, however, the novel is study of Alun Brady and his family, much more a sensitive domestic drama than an action thriller, a study of identity and reality—personal, familial, cultural, and religious—as revealed through a series of unrelenting ironies in which God, fate, and free will do battle.

The action shifts back and forth between twenty-nine-year-old Alun’s immediate past and the earlier past of his childhood, leading up to his three-year imprisonment. Alun has always had many insecurities, usually related to his unfortunate relationship with his much more gifted physician-brother whose casual cruelty and arrogance have made Alun’s life, and sometimes the lives of his parents, miserable. During dinner at the family home, one Sunday after church, for example , brother Will volunteers that Al’s “always been a proper little mummy’s boy,” someone who is now “nearly thirty, he’s never left home, he’s never had a girlfriend…I mean, if he’s not gay he must be a girl. Are you a girl, Al?” Though his mother roars at Will in fury over this attack, Alun dissolves into tears and runs from the room, making no effort to defend himself and leading the reader to wonder what, on earth, someone so sensitive could have done that would lead to a three-year prison sentence. Ironically, Alun regards Will as the “black sheep” of the family.

, brother Will volunteers that Al’s “always been a proper little mummy’s boy,” someone who is now “nearly thirty, he’s never left home, he’s never had a girlfriend…I mean, if he’s not gay he must be a girl. Are you a girl, Al?” Though his mother roars at Will in fury over this attack, Alun dissolves into tears and runs from the room, making no effort to defend himself and leading the reader to wonder what, on earth, someone so sensitive could have done that would lead to a three-year prison sentence. Ironically, Alun regards Will as the “black sheep” of the family.

Shifting quickly to a later time, the author shows Alun as he is released from prison, walking through Cardiff, which has changed significantly since his imprisonment. Except for the sympathetic ghost who has given meaning to his life in prison, Alun has not been visited, even once, especially by anyone in his family, and no one is there to greet him upon his release. Walking miserably around town, Alun observes Will’s house from afar, but decides not to call on him. Instead he spends the night sleeping on his parents’ grave. “My dreams are simple now, any childish fantasy wiped out by prison’s horrors.”

Gradually, author Llwyd Owen builds suspense about Alan and his life. How a sensitive young man who attended church on Sundays, always honored his father and mother, gr

aduated from college, and worked at low pay for six years at a non-profit agency which works tirelessly to promote the difficult Welsh language to Wales and the world could end up sharing a cell with a man who was “the happiest, gentlest murderer I’ve ever met” remains a mystery until Al begins to show his extreme naivete in his dealings after his release. His belief that everyone he meets is good and acting from noble purposes, a belief that he also applies to the acts he himself committed before being jailed, shows Al to be too saintly to survive long in the jungle he discovers after his release.

aduated from college, and worked at low pay for six years at a non-profit agency which works tirelessly to promote the difficult Welsh language to Wales and the world could end up sharing a cell with a man who was “the happiest, gentlest murderer I’ve ever met” remains a mystery until Al begins to show his extreme naivete in his dealings after his release. His belief that everyone he meets is good and acting from noble purposes, a belief that he also applies to the acts he himself committed before being jailed, shows Al to be too saintly to survive long in the jungle he discovers after his release.

Irony builds upon irony here as Alun still tries to live the selfless life which led to his imprisonment for a crime he still believes is not wrong: he has learned nothing about reality. “I’ve given the whole episode so much thought during my sentence that my conscience is clear, and I don’t regret what I did. What I do regret, though was not having the chance to explain my actions to my parents. This fact will haunt me until my dying day.” Even as the reader becomes alarmed at Alun’s increasingly uncertain future as it continues to be revealed upon his release, Alun is still being ingenuous and religious.

With his shifts in points of view and time, the author is able to bring off the character study of Alun with panache, and to develop his themes (which some will ultimately find cynical) in detail. Though the novel has episodes of sentimentality and melodrama, the constant intrusion of often devastating ironies into the plot show the author’s belief that the “perfect” life must also be a life in tune with today’s realities. The conclusion, the most ironic I have read in a long time, bears this out. As the hidden past is inexorably revealed, the author sets up the novel for a tour de force ending that few will ever forget (though some will find it more than a little “convenient”). The dark side of life gets a workout in this novel, and in the process readers discover a great deal about life in contemporary Wales.

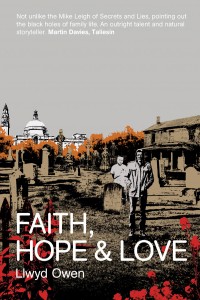

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears here: www.ylolfa.com

The lake photo is of Roath Lake Park in Cardiff, which Will’s house overlooked. The lighthouse in the center is a memorial to Capt. Robert Scott, honoring his departure from Wales on his ill-fated journey to Antarctica in 1910. www.urban75.org

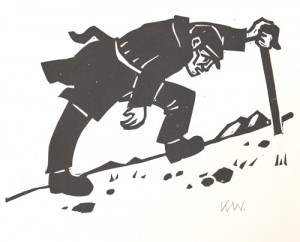

The woodcut at the end is of “The Shepherd” by Kyffin Williams, one of Wales’s greatest artists, a print which Alun’s parents have over the fireplace in their house. http://www.haynesfineart.com