Note: This novel was named one of the Top Ten Literary Fiction titles for 2011 by Publishers Weekly USA.

“So there we are, paper hats on, about to pour the gravy and the phone goes, and Laura’s like, Mum, who’s Nick on the phone to? And I’m like, It’s his dad, darling, he’s just wishing him a Merry Christmas. And the next thing you hear from the conservatory is Nick screaming, And you’re nothing to me either, you old bastard.”—Astrid

It is Christmas , and Nick Goodyew has not seen his father, Ken, in fifteen years, or Pearl, his mother, in twenty. His parents’ acrimonious life together, and their divorce, have come to typify the family’s way of dealing with issues—escape, a way of life for virtually all of them. Pearl left home and divorced Ken when she could not deal with his anger and nastiness a moment longer. Their son Nick, who “committed all sorts of betrayals to get ahead,” turned his back on his poor home and his parents and left, never to return, after he won a scholarship to private school and college. Now he has a new life as a successful attorney, far from Ken and Pearl, with a home in a picturesque town (only twenty miles away), a Range Rover, and Astrid, a beautiful companion. His put-upon brother Dave, still resentful of Nick’s behavior, lives on a farm near Hastings, not far from his father, with his wife and children. Dave has been the only conduit between Nick and the rest of the family, feeling “duty-bound to all parties to pass unkindness back and forth.” His father, unhappily remarried, now believes he is going to die, and, despite the on-going rancor, typified by a surprise Christmas phone call, he still wants to get the family together to make peace with the past. “He’s what you call a hymn short of a funeral service, our dad,” Dave avers.

, and Nick Goodyew has not seen his father, Ken, in fifteen years, or Pearl, his mother, in twenty. His parents’ acrimonious life together, and their divorce, have come to typify the family’s way of dealing with issues—escape, a way of life for virtually all of them. Pearl left home and divorced Ken when she could not deal with his anger and nastiness a moment longer. Their son Nick, who “committed all sorts of betrayals to get ahead,” turned his back on his poor home and his parents and left, never to return, after he won a scholarship to private school and college. Now he has a new life as a successful attorney, far from Ken and Pearl, with a home in a picturesque town (only twenty miles away), a Range Rover, and Astrid, a beautiful companion. His put-upon brother Dave, still resentful of Nick’s behavior, lives on a farm near Hastings, not far from his father, with his wife and children. Dave has been the only conduit between Nick and the rest of the family, feeling “duty-bound to all parties to pass unkindness back and forth.” His father, unhappily remarried, now believes he is going to die, and, despite the on-going rancor, typified by a surprise Christmas phone call, he still wants to get the family together to make peace with the past. “He’s what you call a hymn short of a funeral service, our dad,” Dave avers.

The ensuing novel is a witty and touching examination of all the members of the family as they finally examine their lives, their memories, and their relationships. British author Louise Dean, with her dark sense of humor and her breath-taking ability to suggest attitudes and psychological states through description, arouses sympathy for her characters as they search for ways to communicate and, perhaps in time, forgive each other for the past. Each is individualized, unique, revealing his/her inner life through conversations and the author’s well-chosen details. Seventy-eight-year-old Ken is particularly difficult to like, a man who often uses insults and mockery to hide his own disappointments, and who cannot let any comment pass without an on-going argument. Constantly carping, he believes that everyone else is always wrong. As he approaches his death, he wants his lawyer son Nick to arrange his will, one that will disinherit  his current wife June and her family, his son Dave, and Nick himself, preferring that his estate, whatever it is, will go to Dave’s son, his only grandson. Yet Nick is very much like his vengeful father, emphasizing to Astrid that he will refuse to attend the eventual funeral, blaming Astrid for his own ill-temper and mean-spiritedness, and accusing her of having been responsible for the in-person meeting with his father in the first place.

his current wife June and her family, his son Dave, and Nick himself, preferring that his estate, whatever it is, will go to Dave’s son, his only grandson. Yet Nick is very much like his vengeful father, emphasizing to Astrid that he will refuse to attend the eventual funeral, blaming Astrid for his own ill-temper and mean-spiritedness, and accusing her of having been responsible for the in-person meeting with his father in the first place.

With its emphasis on character, the plot, such as it is, is thin, yet this very moving and memorable novel, however acerbic, is so lively with its dialogue and interior monologues, that it often resembles a play. In one scene, an old high school girlfriend tells Nick, for example, that “You was a really good person once—you know, before you got popular…[Now] you are the sort of person who’d sell his own parents for membership in the right club.” And in a sense, Nick has “sold his parents” by leaving them out of his life for years. When a college friend reminds him about his atrocious behavior on the one time that his mother came to visit him in college, he does not even remember the occasion. Nor does he remember some kindnesses he has received in college from his father. As Nick comes to know himself better through the memories evoked through his conversations with others, he also begins to see his parents—and himself—in new ways.

Scenes alternate among all the main characters, as they begin to communicate and learn more about themselves, where they come from, and where they would like to go. Ken befriends Audrey, who runs a funeral home, volunteering to work for her, and the scenes involving Audrey and Ken at work in the funeral home are some of the darkest, funniest, and most ironic in the book.

Scenes alternate among all the main characters, as they begin to communicate and learn more about themselves, where they come from, and where they would like to go. Ken befriends Audrey, who runs a funeral home, volunteering to work for her, and the scenes involving Audrey and Ken at work in the funeral home are some of the darkest, funniest, and most ironic in the book.

Every detail of description counts here, enlivening the characterizations as the author creates a broad picture of how they communicate (or not), of families and family heritage, of love and how it “works,” and about death and memory. When Ken and Nick finally meet for the first time in years, “They were two men pulling their coats to, in the wind. They held their faces sideways onto each other. Each seemed to find something in the distance to dismay him. When Nick stuffed his hands into his pockets, his father did the same. When he spoke, he jerked his head. When his father spoke, he jerked his head, too…Nick went to take his father’s arm. He was shaken off.” When Astrid introduces herself to Dave’s wife: “Astrid gave a bunch of white lilies to Marina and the women exchanged cheek kisses and fell promptly into the self-deprecation that is the stock-in-trade of women who want to play nicely.” When Ken, the “old romantic” of the title, is working at the funeral home, “Like a dog on wheels being pulled in fits and starts, he goes mechanically along the corridor past the two  chapels of rest. He peeps into one of them. It’s a narrow room, just big enough for a coffin…The point of focus behind the head of the coffin is a stained-glass window with a brass crucifix on its ledge and, on a lower shelf, the alternative option, a white porcelain dove. ‘I’ll have the cross,’ he says wearily. ‘Stuff the dove.’ ”

chapels of rest. He peeps into one of them. It’s a narrow room, just big enough for a coffin…The point of focus behind the head of the coffin is a stained-glass window with a brass crucifix on its ledge and, on a lower shelf, the alternative option, a white porcelain dove. ‘I’ll have the cross,’ he says wearily. ‘Stuff the dove.’ ”

Completely absorbing from beginning to end, The Old Romantic raises the bar for “domestic” novels, presenting unique and interesting characters working through personal problems and learning, at last, from their interactions. One of my Favorites for the Year.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo, attributed to fig tree, is from http://www.list.co.uk

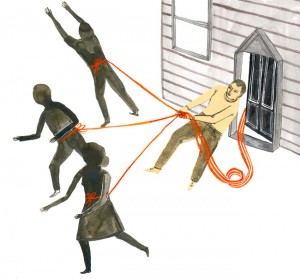

The cartoon drawing of the action of the novel, done by Kaye Blegvad, introduced a review of this book on http://www.nytimes.com

An old gamekeeper’s cottage, similar, perhaps, to where Pearl lives, is seen here:  http://www.hiddenrealms.org.uk

http://www.hiddenrealms.org.uk

Note: Louise Dean’s THIS HUMAN SEASON (2007), is a completely different type of book, a powerful study of the hunger strikes and riots by political prisoners held at Long Kesh Prison (The Maze) during the 1970s turmoil between Ireland and Northern Ireland. Evidence of the amazing versatility of this young writer who has received critical praise on both sides of the Atlantic.