“My role is to see, describe and, now, write about what I saw. Someone or something is using me to untangle the tangled plot over whose direction I have as little influence as the pen has over the poets who wield it, or man over the gods who manipulate him, or the knife over the murderer.”

One of the m ost original and delightful novels of 2005, Borges and the Eternal Orangutans is simultaneously a literary detective thriller, a parody of the detective story, and an anti-detective story. Taking its title (and one of its primary images) from Elizabethan writer John Dee, who wrote that if an orangutan were given enough time, he would eventually produce all the books in the world, the novel takes place in Buenos Aires, where an international group of Edgar Allan Poe specialists gathers for a meeting of the mysterious Israfel Society.

ost original and delightful novels of 2005, Borges and the Eternal Orangutans is simultaneously a literary detective thriller, a parody of the detective story, and an anti-detective story. Taking its title (and one of its primary images) from Elizabethan writer John Dee, who wrote that if an orangutan were given enough time, he would eventually produce all the books in the world, the novel takes place in Buenos Aires, where an international group of Edgar Allan Poe specialists gathers for a meeting of the mysterious Israfel Society.

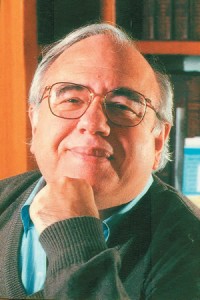

Brazilian author Luis Fernando Verissimo creates as his narrator, a 50-year-old man named Vogelstein, who has led a cloistered life, “without adventures or surprises.” He believes that he has been called to the conference by destiny–“some hidden Borges”–and the convenient death of his cat confirms this belief. For years Vogelstein has wanted to meet author Jorge Luis Borges, who is attending the meeting. He once translated a Borges story for “Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine,” creating and tacking on a new conclusion—a “tail”—to “improve” its inconclusive conclusion. He has been trying to make amends with the horrified author ever since.

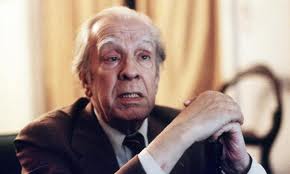

Addressing the novel to the blind Borges, Vogelstein describes how, during the conference, he discovered the bloody body of Rotkopf, the most argumentative speaker, in his hotel room. Two other speakers wanted Rotkopf dead. Borges and Vogelstein team up, applying their talents to solving the cryptograms Vogelstein believes were hidden within the murder scene and in the position of the victim’s body. Throughout the investigation, Vogelstein and Borges study the tales of Poe for help, while they simultaneously explore the origins of language, the work of John Dee and the “Necronomicon” (publicized by H. P. Lovecraft), the Kabbalah, the occult, the Gnostic gospels, apochrypha, and the “eternal orangutan.” “Everything is a message,” Vogelstein declares, “even the shape made by the hairs in your bar of soap.”

Jorge Luis Borges

Beautifully translated into colloquial and lively English by Margaret Jull Costa (who has also translated the worlds of Jose Saramago and Julio Llamazares), this wildly imaginative literary detective story fully engages the reader with its tongue-in-cheek humor, its erudition, and its parallels with Poe. Like some of Poe’s protagonists, Vogelstein proves to be an unreliable narrator, always saying what he believes will impress his idol, Borges. Often acting like an excited child, Vogelstein serves as a blundering foil, both for the more august Borges and for the criminologist Cuervo, who wishes the dead man had “simply told [Vogelstein] the name of the murderer over the phone, instead of making such a complicated game of it.” Scholarly in its allusions and in the concepts which underlie the mystery, the novel’s earnest tone and enthusiastic investigation of arcana create a fun-filled mystery/parody sure to delight lovers of literary fiction. (On my Favorites list for 2005)

Notes: Also reviewed here: Verissimo’s CLUB OF ANGELS

The author’s photo appears here: http://republicadolivroteen.blogspot.com

The photo of Borges by Eduardo di Baia/AP is from http://www.guardian.co.uk