Note: This novel was WINNER of the Guardian First Novel Award for 2010.

“What was the point of a life so wounded?…If it was only an unlucky accident, then everything was an accident, only a stark grid of cause and effect. And if that’s the case, then nothing has meaning beyond the question of whether an event will cause pain; the only thing that can matter is to be free of pain, just as in the life of an animal, and to avoid causing or allowing unnecessary pain, which is the responsibility of humans.”–Sunny Taylor, nurse at Suvanto

A sanitorium set in Suvanto in rural Finland, sometime in the late 1920s, has drawn female patients from all Europe and America. The “up-patients,” primarily wealthy women who enjoy the specialized spa treatments and the chance to escape from their everyday lives for periods of up to six months, live on the top floor above those who are physically ill. One physician asserts that “these are bored women, powdered and perfumed for dinner….They like being sick. That’s all they talk about. Even at dinner they keep talking about…personal details not appropriate for the dinner table.” A young American nurse, Sunny Taylor, who has taken a job here to escape the difficult memories of her own life up to this point, is also hard pressed to be completely sympathetic of those who go “too far into self-indulgence, [those who] won’t do much more than eat cookies and make conversation with the nurses…Real need is one thing, but choosing frailty is another.” Yet Sunny sees beyond the physical details, recognizing that though some “are here only to have their pain–or their discomfort–cultivated and indulged,” they all do experience real pain, some more intensely than others. They may react to pain differently and try to assuage it differently, but they are all unhappy with their lives “outside.”

Suvanto in rural Finland, sometime in the late 1920s, has drawn female patients from all Europe and America. The “up-patients,” primarily wealthy women who enjoy the specialized spa treatments and the chance to escape from their everyday lives for periods of up to six months, live on the top floor above those who are physically ill. One physician asserts that “these are bored women, powdered and perfumed for dinner….They like being sick. That’s all they talk about. Even at dinner they keep talking about…personal details not appropriate for the dinner table.” A young American nurse, Sunny Taylor, who has taken a job here to escape the difficult memories of her own life up to this point, is also hard pressed to be completely sympathetic of those who go “too far into self-indulgence, [those who] won’t do much more than eat cookies and make conversation with the nurses…Real need is one thing, but choosing frailty is another.” Yet Sunny sees beyond the physical details, recognizing that though some “are here only to have their pain–or their discomfort–cultivated and indulged,” they all do experience real pain, some more intensely than others. They may react to pain differently and try to assuage it differently, but they are all unhappy with their lives “outside.”

The arrival of Julia Dey, a woman with a gynecological infection, changes the atmosphere from what it has been in the past. Julia is often mean-spirited and sometimes deliberately cruel. She can sleep during the day but is awake with nightmares at night, and she often wanders. Her language, chosen deliberately, is often intended to disgust those around her. Gradually, the lives of the women and their difficulties unfold–Pearl Weber, beautiful and spoiled; Laimi Lehti, a more rational, less fussy patient; and Mary Minder, who “lives in the moment,” and arrives wearing red shoes to match her luggage and her suit. All have sought escape here, as they have done in previous years. They are friends, squabbling, gossiping, and overanalyzing their problems and complaints, and Julia sees them as fair game, quickly zeroing in on them.

Dr. Peter Weber, the physician in charge of the hospital, believes that most of their problems are gynecological, and he is developing a special stitch which he believes will cure some of their problems. This, in combination with hysterectomy, may lead him to fame, he believes–if he can get his research done in this rural hospital without oversight. It is his surgery on one of the women which leads to the climax and the long denouement, as the conflicts demand resolution.

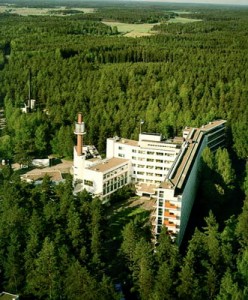

Paimio sanitorium

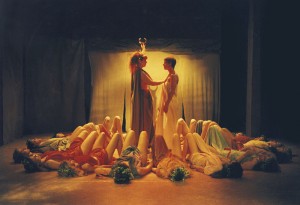

In several places throughout this debut novel, author Maile Chapman refers to the action of Euripedes’ The Bacchae, and though the parallels between that early Greek play and this contemporary novel are not exact, many of the themes become clearer when considered in view of that play. The women known as “bacchae” in Greek mythology were sometimes considered madwomen, who, acting together, enacted their own vengeance and appeared to be unconquerable. It may be this trait which has led some critics to call this a “proto-feminist” novel. The novel, like the play, also depends on sets of contrasts for its action and its characters’ behavior: civilization vs. savagery, freedom vs. control, the rational vs. the irrational, order vs. chaos, and even men vs. women. The parallels, though perhaps implied, are not fully developed, however, and the shallow lives of the female “up-patients” certainly do not represent any ideal to which feminists aspire. Nevertheless, the conflicts do get resolved eventually, and, with echoes of the Greek chorus reverberating throughout the conclusion, many readers will feel that vengeance is enacted and the balance of the universe restored in ways similar to the Greek tragedy.

Patient's room, ca. 1929

The novel is dark, almost claustrophobic in its intensity. The nauseating descriptions and language which the chaotic Julia Dey employs in her relationships stand in stark contrast to the author’s often beautifully lyrical descriptions of the weather as it changes with the seasons. By leaving much up to the reader and not spelling out what is happening in the latter part of the book, she avoids the trite and the cliched and keeps her novel mysterious and atmospheric. The novel is often frustrating, however. The characters are not likable and rarely inspire sympathy, and the author’s real purpose is not clear. The long descriptions of individual patients would be far more helpful if these characters were, in fact, the dominant characters, but we often get much description of people who, it turns out, are peripheral to the real action. The idea of the women as victims (i.e., choosing to be victims), as they so often seem to be here, counteracts the idea that these are real bacchae (and feminists), and for most of the novel, the staff are too ineffective to be a legitimate dramatic foil to the patients. Chapman is an enormously talented writer with a smooth style and sense of drama, however, and many readers will look forward with anticipation to her next novel.

Notes: The author’s photo accompanies an interview on http://www.guardian.co.uk

The photo from a production of The Bacchae may be seen on http://en.wikipedia.org Photo by Brad Mays.

The author indicates in her Acknowledgments that she visited the Paimio Sanitorium in Paimio, Finland, and used it as the model for Suvanto. Paimio was built (1929 – 1933) by renowned architect Alvar Aalto. The photo here shows it in its wilderness setting, similar to that of Suvanto: www.artnet.com.

The photo of a patient’s room at Paimio, circa 1929, is posted on this site: www.aecbytes.com