It was one of the most notorious murders of its age. Galvanizing early twentieth-century Britain and before long the world, it involved a patrician victim, stolen diamonds, a transatlantic manhunt, and a cunning maidservant who knew far more than she could ever be persuaded to tell. It was…“as brutal and callous a crime as has ever been recorded in those black annals in which the criminologist finds the materials for his study.” – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1912.

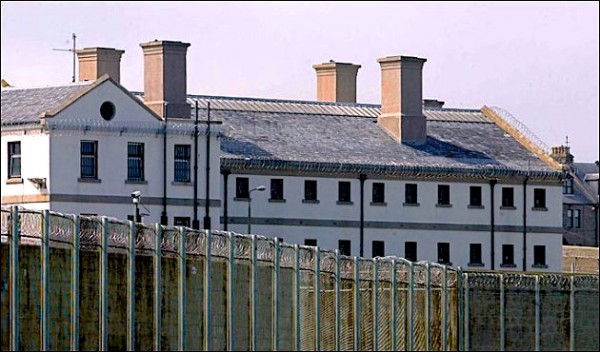

Though the name of the victim, the circumstances of her murder, the trial of a suspect, and his conviction have long faded from public memory in England and Scotland – and have had almost no publicity at all in the US – the “dark drama” of this case takes on new meaning for a reader as soon as Conan Doyle’s name appears in the title of this book. Here Conan Doyle does not appear as an author inventing a story, however clever and astute his Sherlock Holmes novels may be. In this beautifully structured work by New York Times author Margalit Fox, Conan Doyle becomes instead a participant in the real life events. He, like Sherlock Holmes, must carefully examine all aspects of a confusing case, the motivations behind the actions of all the people involved in it, and the end results, even when those differ from what he believes they should have been. Conan Doyle becomes human here, a man involved in trying to help an immigrant he believes has been used as a pawn by the police and public officials, one who has been the victim of false testimony by “witnesses,” and one who will eventually serve eighteen years of a life sentence before he is released from Peterhead Prison where he has spent his life at hard labor, mining granite.

Though the name of the victim, the circumstances of her murder, the trial of a suspect, and his conviction have long faded from public memory in England and Scotland – and have had almost no publicity at all in the US – the “dark drama” of this case takes on new meaning for a reader as soon as Conan Doyle’s name appears in the title of this book. Here Conan Doyle does not appear as an author inventing a story, however clever and astute his Sherlock Holmes novels may be. In this beautifully structured work by New York Times author Margalit Fox, Conan Doyle becomes instead a participant in the real life events. He, like Sherlock Holmes, must carefully examine all aspects of a confusing case, the motivations behind the actions of all the people involved in it, and the end results, even when those differ from what he believes they should have been. Conan Doyle becomes human here, a man involved in trying to help an immigrant he believes has been used as a pawn by the police and public officials, one who has been the victim of false testimony by “witnesses,” and one who will eventually serve eighteen years of a life sentence before he is released from Peterhead Prison where he has spent his life at hard labor, mining granite.

Though Conan Doyle is mentioned in a few places early in the book, he is not an active part of the story until the second half of the book, which actually benefits from his delayed involvement in the narrative. This provides author Margalit Fox with the opportunity to recreate the broad panorama of contemporary social and judicial issues which affected the outcome of this case, and she leaves nothing to chance. Even the selection of typeface for the book, one called Caslon, reflects the period in which the original case would have been printed and adds immeasurably to the visual effect of the book. Throughout, she refers to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle by the name “Conan Doyle,” which is how he would have been addressed in his own time. She provides a three-page cast of characters at the end of the book for reference, along with a helpful glossary of legalese and local terminology (“identity parade” in place of “lineup,” and “production” in place of “exhibit,” for example). Twenty-four pages of photographs, including a small (and still readable) message carried in the mouth of a fellow prisoner, make the people, places, and details of the case come vitally alive for the reader.

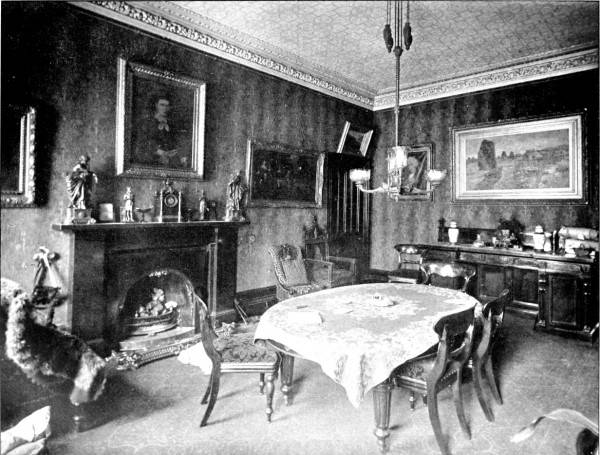

The case itself involves Marion Gilchrist, a woman almost eighty-three years old, daughter of a prosperous engineer in Glasgow, for whom she acted as caretaker in his old age. While she was doing this, she also appears to have convinced him to change his will, leaving most of his estate to her, and omitting her siblings and their children. Then, a month before her own death, she changed her will, leaving everything to a former maid and her daughter – not the maid who had been working at her house for the past three years. The current maid, Helen “Nellie” Lambie, had left the house for ten minutes on December 21, 1908, to pick up a newspaper, and it was during this tiny window of time that Miss Gilchrist was murdered at home. When Nellie returned to the house after her errand, she passed a man leaving the house and indicated to someone that she recognized the man, the probable murderer, and that it was someone Miss Gilchrist knew well – otherwise, Miss Gilchrist would never have admitted him to the house. Nellie was also thoroughly familiar with the secret places in the house where Miss Gilchrist’s jewelry was hidden, and she would have been able to identify a key piece, a crescent-shaped brooch, the only piece of jewelry which was stolen during the murder.

Using alternating narratives dealing with Miss Gilchrist and Oscar Slater, who was arrested and tried for the murder, Fox slowly reveals details, keeping the interest high, even though many of the facts of the case are known from the beginning. Slater, a Jewish immigrant, arrived in Scotland from Europe in the autumn of 1908. He had lived in Glasgow before, and briefly also in New York, London, Paris, and Brussels. Much of his wandering was with his mistress, some say a prostitute, while he was also working as a pimp, card sharp, and shady operator. He often used the alias A. Anderson, and he lived only five minutes from Miss Gilchrist at the time of her death. After the crime, however, the police found him gone, on his way to New York on the Lusitania. They arranged to have him arrested in New York and returned to Scotland, where he eventually faced trial, conviction, and a life sentence at hard labor. Though Slater had never been violent, he was an immigrant and Jewish at a time when anti-Semitism was strong, and the police, anxious to get the case off their hands, consistently ignored inconvenient facts and promoted new stories by witnesses whose changing memories kept Slater as the main suspect and eventually guilty party.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries and real-life investigator of this mystery.

Conan Doyle was one of several writers and journalists who became interested in this case early on, but it was not until fifteen years after Slater had started serving his sentence that his case attracted enough interest for it to be reconsidered by the courts. Conan Doyle, a physician, applied some of the same kinds of diagnostics and emphasis on small details to raise questions about Slater’s case, just as he did with Sherlock Holmes. He also raised public questions regarding why the police pursued Slater so ardently when the evidence of his involvement was completely disproved in the first week of the investigation. Bigotry and his class identity obviously played strong roles in his conviction. This is not to say that Slater was in any way a diamond in the rough, but he was legally innocent, and Conan Doyle was instrumental in getting him released. Immediately following the release, however, his behavior so outraged Conan Doyle that any relationship they might have had disappeared forever. After withdrawing his own angry lawsuit against Slater, Conan Doyle eventually put the case to rest on a high note: “At the time, the man’s ingratitude hurt me deeply,” he wrote in 1930, “but I have reflected since that one could hardly go through eighteen years of unjust imprisonment and yet emerge unscathed.” A superb record of a real case involving Conan Doyle and a real murder in pre-World War I Scotland.

The old Peterhead Penitentiary, where Oscar Slater served eighteen years at hard labor.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://in.pinterest.com

The dining room of Miss Gilchrist’s house, where her body was discovered: https://commons.wikimedia.org

The combined photo of Miss Marion Gilchrist and Oscar Slater may be found on http://oldglasgowmurders.blogspot.com/

The portrait of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is from https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com

The Peterhead Penitentiary, where Oscar Slater spent eighteen years, is shown on https://theukdatabase.com/