“A cat, a flask of poison, and a radioactive source are placed in a sealed box. If an internal monitor (e.g. Geiger counter) detects radioactivity (i.e. a single atom decaying), the flask is shattered, releasing the poison, which kills the cat…Yet, when one looks in the box, one sees the cat either alive or dead, not both alive and dead.” —Wikipedia, entry for “Schrödinger’s Cat.”

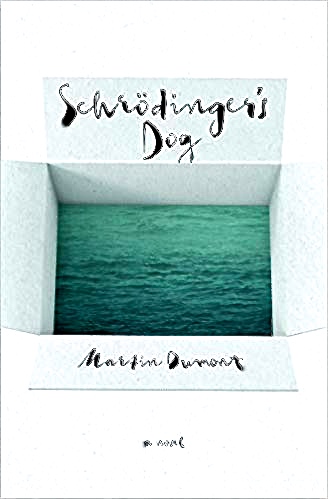

Although the complex thought experiment by Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger in 1935, described in the above quotation, may seem like an odd and highly esoteric principle around which to mold this sensitive and emotion-filled novel about a man and his dying son, debut novelist Martin Dumont uses it as the unobtrusive crux of his story and part of its dramatic conclusion.

Although the complex thought experiment by Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger in 1935, described in the above quotation, may seem like an odd and highly esoteric principle around which to mold this sensitive and emotion-filled novel about a man and his dying son, debut novelist Martin Dumont uses it as the unobtrusive crux of his story and part of its dramatic conclusion.

In doing so, he achieves a kind of originality I myself have never before encountered in literary fiction. Many other readers like me, who never studied physics and never even thought of the principle described in the introductory quotation to this review, may wonder if this short book itself is one which will “resonate” for them, or at least keep them interested in the story from beginning to end. While I cannot speak to the experiences of others, I can say that I found Schrödinger’s Dog by French author Martin Dumont to be one of the best and most insightful debut novels I have read in years. Reading it in two sittings, I was completely engaged both emotionally and intellectually, and I still cannot stop thinking about it, coming to new realizations each time I reflect on its themes of perception, reality, time, and death and their interrelationships. Except for the novel’s title, in which a dog is substituted for “Schrödinger’s cat,” because the main character prefers dogs to cats, the physics that makes this story so hypnotic and its conclusion so satisfyingly elusive is hidden within, just as Schrödinger’s cat or dog, hidden within its box, is both alive and dead.

As the novel opens, a man is lying in bed thinking there is someone on the other side of the wall, and as he stays in bed, wondering if it is his son or a burglar, he realizes that he can get up and see, yet he stays in bed. “At bottom, it’s almost a game: someone’s walking around on the other side of the wall: it’s not Pierre, it’s not a burglar; it’s as if they were superimposed…As long as I don’t make sure, it’s a little bit of both.” When the man, Yanis, finally gets up, he finds his son sitting outside on the balcony eating cookies and milk. A taxi driver, Yanis works both day and night, as his son Pierre, a third-year biology student in a local college, studies hard and spends his free time with the college drama club, for which he is writing a new play. Pierre’s departure for campus leaves Yanis to remember his deceased wife Lucille, a kindhearted woman who was so engaged in all kinds of humanitarian causes that she was often unaware that some people were taking advantage of her. Though Yanis does not go into detail, it is clear that he lost her some time ago, even after her “stay” at a clinic.

That weekend Yanis and Pierre drive four hours away to “the Island” to go diving and stay with Lucille’s parents. Pierre is tired and appears ill, and has some symptoms which alarm Yanis, but they both love free diving and the escape it provides from real life. A trip to the hospital after their return home determines that Pierre needs surgery for a tumor, an operation which does not result in the expected happy ending. As Yanis sits in an office awaiting an oncologist, he sees Pierre’s future as consisting of “a crowd of eventualities with their probabilities. As long as no one opened the door, reality remained free: it could head in any direction at all….One word too many, one expression, or one opening door – and the conditional is dead. If only the door handle wouldn’t move. If only the door would remain closed forever.” After meeting with the oncologist, Yanis realizes the sad and probably inevitable fate awaiting Pierre, and he recalls Lucille’s death in a car crash. An inquest showed that she had been behaving in very uncharacteristic ways, and the question arose as to whether the “accident” was really an accident. The police say, “yes,” an accident; Yanis thinks, “no, a rational choice.” Since no one will really know, for sure, that death will remain “in between the two.”

Hospitalized as he recovers from surgery, Pierre eventually finishes writing his book, and he asks Yanis to try to find an editor and publisher for it, actions to which Yanis devotes every available moment. He is determined to get Pierre’s book published as the only final, meaningful gift he can give to him. The second half of the novel focuses on some new plans Yanis has regarding Pierre’s book. At the same time, he begins to resolve some other issues which have disturbed him for years. Though he has never been friendly with Lucille’s parents, he reluctantly agrees to meet with them when they invite him for dinner after a visit with Pierre. Breaking down when they talk of Lucille, he asks his father-in-law how he “does it,” but the old man does not understand. As Yanis explains his long-held doubts about Lucille’s death, the old man explains that “It’s like a box, Yanis…a box you can’t open…The truth died with Lucille. Forever. Now there are only some suppositions. Some maybes, and the weight you decide to give them….You choose….Decide on reality, your reality, the one you’ve chosen. It won’t be worth less than any other ones, don’t you think?”

Hospitalized as he recovers from surgery, Pierre eventually finishes writing his book, and he asks Yanis to try to find an editor and publisher for it, actions to which Yanis devotes every available moment. He is determined to get Pierre’s book published as the only final, meaningful gift he can give to him. The second half of the novel focuses on some new plans Yanis has regarding Pierre’s book. At the same time, he begins to resolve some other issues which have disturbed him for years. Though he has never been friendly with Lucille’s parents, he reluctantly agrees to meet with them when they invite him for dinner after a visit with Pierre. Breaking down when they talk of Lucille, he asks his father-in-law how he “does it,” but the old man does not understand. As Yanis explains his long-held doubts about Lucille’s death, the old man explains that “It’s like a box, Yanis…a box you can’t open…The truth died with Lucille. Forever. Now there are only some suppositions. Some maybes, and the weight you decide to give them….You choose….Decide on reality, your reality, the one you’ve chosen. It won’t be worth less than any other ones, don’t you think?”

As the novel works its way closer to Pierre’s inevitable death, Yanis visits with his friend Francois and wonders whether it is better to lie if it makes another person happy, then reminisces about Pierre and his childhood. He begins to bring Pierre books from the bookstore every time he visits him in the hospital, each of them clinging to a reality he believes will keep Pierre from “going under.” It is not until the last ten pages of the novel that Schrödinger is mentioned at all, this time in the context of a nurse talking with Yanis, and she gives him yet another way of thinking about Pierre and the reality of his upcoming death. The final scenes are unforgettable, and very satisfying, though not in ways I would have expected. Ultimately, the reader is forced to grasp the inherent peace which may be possible if one can appreciate the “dog” that may be simultaneously alive and dead. Author Martin Dumont has produced a novel so unusual and so effective – at least for this non-scientist – that I know it will be one I will read again and again, each time with total satisfaction and new realizations.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://otherpress.com

The free-dive picture is from https://freediveinternational.com

“Palliative care” is a medical approach in which medical care optimizes the quality of life and mitigates suffering among people with complex, often fatal illnesses. https://smrhfoundation.com

The drawing symbolizing Schrödinger’s cat, both alive and dead at the same time, appears on http://nautil.us