Note: Max Porter is WINNER of the Dylan Thomas Award for 2016. He was also SHORTLISTED for both the Guardian First Novel Award and for the Goldsmith’s Prize, 2015.

“[The Boys] played at birds, they played at lions. They went through phases: dinosaurs, trucks, Thundercats, kung fu, lying, sport. There was very little division between their imaginary and real worlds, and people talked of coping mechanisms and normal childhood and time. Many people said ‘You need time,’ when what we needed was washing powder, nit shampoo, football stickers, batteries, bows, arrows, bows, arrows.”—Dad, early in the grieving process after the loss of his wife.

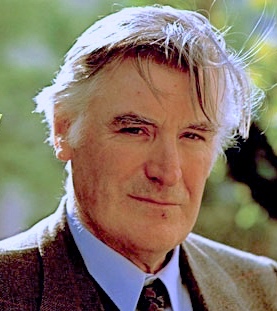

In an electrifying novel that uses simple images and straightforward, often abbreviated thoughts to create deep emotions and subtle themes, debut novelist Max Porter revitalizes the whole concept of the novel, creating a work that includes elements of many different literary styles which offer constant surprises as the novel shifts and turns in its focus. Despite these constantly changing structural elements, the voices of Dad and his Boys remain direct, unpretentious, and realistic as they tell of their reactions to the sudden death of their wife and mother from an accident which has left them overwhelmed by events and not sure how to react or acknowledge what they feel. In a consummate irony, Dad, an academic writer, has been working on a book, overdue at the publisher, called Crow on the Couch: A Wild Analysis, which examines the poems of Ted Hughes following the death of his wife, Sylvia Plath.

In an electrifying novel that uses simple images and straightforward, often abbreviated thoughts to create deep emotions and subtle themes, debut novelist Max Porter revitalizes the whole concept of the novel, creating a work that includes elements of many different literary styles which offer constant surprises as the novel shifts and turns in its focus. Despite these constantly changing structural elements, the voices of Dad and his Boys remain direct, unpretentious, and realistic as they tell of their reactions to the sudden death of their wife and mother from an accident which has left them overwhelmed by events and not sure how to react or acknowledge what they feel. In a consummate irony, Dad, an academic writer, has been working on a book, overdue at the publisher, called Crow on the Couch: A Wild Analysis, which examines the poems of Ted Hughes following the death of his wife, Sylvia Plath.

The book opens with a dialogue in which one of the Boys remarks “There’s a feather on my pillow.” An unnamed voice comments, “Pillows are made of feathers, go to sleep.”

“It’s a big, black feather.”

“Come and sleep in my bed.”

“There’s a feather on your pillow too.”

“Let’s leave the feathers where they are and sleep on the floor.”

It’s been five days since the death, and Dad and the boys are alone now. All the family and visitors have left, the boys finally get to sleep, and “Grief felt fourth-dimensional, abstract, faintly familiar.” Suddenly the doorbell rings, and when Dad opens it, “there was a crack and a whoosh and [he] was smacked back, winded, onto the doorstep…There was a rich smell of decay, a sweet furry stink of just-beyond-edible food, and moss, and leather, and yeast.” As he is lifted above the tiled floor, he finds feathers between his fingers, in his eyes, and in his mouth. Crow has arrived, promising he will stay there until he is no longer needed. He is, he says, a “friend, excuse, deus ex machina, joke, symptom, figment, spectre.” Dad recognizes that Crow is almost certainly his own creation, just as he was Ted Hughes’s creation after the death of his wife, and he “wishes [he] hadn’t been obsessing about this thing [Hughes’s poem Crow] just when the greatest tragedy of [his] life occurred.”

Ted Hughes, widower of Sylvia Plath, and author of CROW ON THE COUCH: A Wild Analysis

With Crow incorporating wild and unexpected elements, including humor, into this book about grief, the novel explores death and its aftermath in new ways. Crow sees himself as a “template…a myth to slip up into,” something he knows Dad also recognizes. Crow usually finds humans dull, except in grief, but “Motherless children are pure crow. For a sentimental bird it is ripe, rich, and delicious to raid such a nest.” He empathizes with the Boys, who do not understand why life has suddenly become so quiet – not what they would have expected from an event as big as death: “Where are the fire engines? Where is the noise and clamour of an event like this…There should be men in helmets speaking a new and dramatic language of crisis. There should be horrible levels of noise….” Crow quickly solves that problem.

As the novel continues chronologically, Dad and the boys deal with their new, unwelcome lives, yet Crow’s surprising actions and stories often help to keep the grief in perspective, preventing it from overwhelming the narrative. Crow sits on Dad’s shoulder as he tries to work on his book, and he babysits for the Boys, at one point assigning them the task of making a model of their mother, “just as you remember her,” promising to bring the winning model to life. Unfortunately, Crow has failed to  realize how seriously the Boys will take this task. The boys grow further in their understanding when their Gran is dying. She tells them to smoke cigarettes like hers, “and one day you too will wheeze like me. The daisies on my grave will puff and wheeze, you mark my words,” a sardonic remark which keeps the episode from becoming maudlin. Dad relives aspects of his life, his courtship, early marriage, and the birth of his children, the genre of each section changing with the subject.

realize how seriously the Boys will take this task. The boys grow further in their understanding when their Gran is dying. She tells them to smoke cigarettes like hers, “and one day you too will wheeze like me. The daisies on my grave will puff and wheeze, you mark my words,” a sardonic remark which keeps the episode from becoming maudlin. Dad relives aspects of his life, his courtship, early marriage, and the birth of his children, the genre of each section changing with the subject.

Poetry, letters, simple lists, a short tale followed by comprehension questions, a geometry problem, simple memories (the boys getting into trouble for flecking the mirror with toothpaste), more complex dreams for the future (Dad wanting to build his wife a monument in Hyde Park with his bare hands), and Crow describing bad dreams and fighting a demon to the death when it challenges the family are all part of the narrative. In Part III, Dad, the Boys, and Crow begin to come to terms with their lives, and by the end of the novel, Crow – and Dad – are ready to part company, leading to a finale worthy of this extraordinary and original book.

Dad wants to build his wife a memorial a hundred feet high in Hyde Park, much like this one of Queen Victoria. Photo by Chris Brown.

When asked in an interview in The Guardian (by Sarah Crown, September 12, 2015), the author explains that this story of death originated from his memories of his own father’s death when the author was six, and though his own family was larger and more complicated than the family in this novel, he did use some of his own observations as a six-year-old in the Boys’ tale of grief. Now married and the father of three, Porter’s feelings for his own children obviously affect his point of view in Dad’s sections, and like Dad, Porter has also been a huge fan of poet Ted Hughes for many years. His admiration for Emily Dickinson, too, is revealed in his title, which is a twist on Dickinson’s poem “Hope is the thing with feathers.” Another Dickinson poem, “That love is all there is,” becomes, with some editing, the introductory epigraph of this book, a humorous twist which sets the tone of the novel. Unique in its structure, imagery, and the character of wild Crow, the book is simple and uncomplicated in its appeal to the reader’s own understandings of life, death, grief, dreams, and reconciliation, while offering new ways to think about these universal themes as the book comes to a perfect conclusion – “Unfinished. Beautiful, Everything.”

Also by Max Porter, Lanny.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://wearewhitefox.com

The Ted Hughes photo is from http://ghpoetryplace.blogspot.com

The crow may be found on https://www.pinterest.com

The statue of Queen Victoria by Chris Brown appears on https://commons.wikimedia.org

ARC: Graywolf