“In spite of all the wrong turns, [the country] was growing in power and prestige, always expanding and getting bigger. It was making goods of all kinds, from needles to rockets, and broadcasting a wonderful new and humane trend in the life of humanity. But what was the point of all that if people were so feeble and downtrodden that they were not worth a fly, if they had no personal rights, no honor, no security, and if they were being crushed by cowardice, hypocrisy, and desolation?”

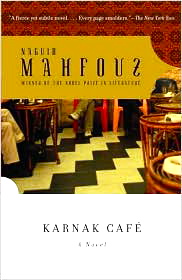

In this pow erful novella by Naguib Mafouz, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988, a narrator stops in at the Karnak Café, an off-the-beaten-path café in Cairo run by Qurunfula, a former belly dancer, famous because she raised her craft to the level of true art. Recognizing her immediately, despite the passage of time since her prime, the narrator, a great admirer, stays and visits. He is soon seduced by the atmosphere in the café and by the charm of a small group of regulars–three old men, three young people, and the PR director of a company—who, along with the steward behind the bar, a waiter, and the bootblack, visit each other every day at the café and create their own urban “family.”

erful novella by Naguib Mafouz, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988, a narrator stops in at the Karnak Café, an off-the-beaten-path café in Cairo run by Qurunfula, a former belly dancer, famous because she raised her craft to the level of true art. Recognizing her immediately, despite the passage of time since her prime, the narrator, a great admirer, stays and visits. He is soon seduced by the atmosphere in the café and by the charm of a small group of regulars–three old men, three young people, and the PR director of a company—who, along with the steward behind the bar, a waiter, and the bootblack, visit each other every day at the café and create their own urban “family.”

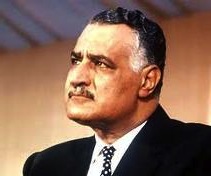

Written in 1974 and newly translated by Roger Allen, the novel takes place in the mid-1960s and focuses on the Karnak Café regulars as they respond to some key moments in contemporary Egyptian history. For the young people, “history began with the 1952 Revolution,” in which the army, led by a young officer named Gamal Abdel Nasser, overthrew King Farouk, abolished the pro-British monarchy, and established a republic, inspiring other Middle Eastern and north African countries in an Arab sovereignty movement. In 1954, Nasser became President of Egypt. Hopes were high then and continue to be high for the young at the café in the early 1960s, despite the acknowledged (and continuing) problems with civil rights, poverty, and abuses by the police.

The three young people and their fates become the focus of the narrator when the young people inexplicably disappear for several months. One of them, Hilmi Hamada, has been the lover of Qurunfula, a love relationship which has given her life new meaning. Hilmi, his friend Isma’il al-Shaykh, and Isma’il’s love, Zaynab Diyab, have all been arrested, supposedly because they are involved with the fedayeen movement, a militant Islamic movement which might threaten the current government. After several months of incarceration under deplorable conditions, which they describe after their release, they are found innocent, and they try to continue their previous lives—until they are arrested and imprisoned again, this time on the suspicion that they are Communists.

Gamal Abdel Nasser, their President, has been involved in the formation of the Palestine Liberation Organization, and when the PLO begins to challenge Israel militarily, and the problems escalate, the scene is set for an Egyptian incursion to protect the Sinai, resulting in the Six Day War in 1967 with Israel. The three young people from the Karnak Café are imprisoned during this time, and when they are released, following Egypt’s defeat, they are devastated, their hopes for their future dashed. “All of us need time so we can bandage our wounds and purify the collective national soul,” Zaynab says.

Mahfouz develops treme ndous suspense about the eventual outcomes of the regulars of the Karnak Café, at the same time that he creates an intense look at the pressures placed upon them as they try to live their lives and do what they think is right. As the forms of torture the young people undergo are revealed, the taboos of the society become obvious, and the faith of the young people in the future of the revolution of 1952 is put to the test. The progress of the country is obvious through their comments, at the same time that the limitations of the country, obvious through their treatment by the military and police, are even more obvious. The desire for “freedom” never flags, at the same time that the powers that be consider “freedom” to be dangerous because of the potential for growth of the fedayeen, the communist movement, and socialism, which would threaten national security.

ndous suspense about the eventual outcomes of the regulars of the Karnak Café, at the same time that he creates an intense look at the pressures placed upon them as they try to live their lives and do what they think is right. As the forms of torture the young people undergo are revealed, the taboos of the society become obvious, and the faith of the young people in the future of the revolution of 1952 is put to the test. The progress of the country is obvious through their comments, at the same time that the limitations of the country, obvious through their treatment by the military and police, are even more obvious. The desire for “freedom” never flags, at the same time that the powers that be consider “freedom” to be dangerous because of the potential for growth of the fedayeen, the communist movement, and socialism, which would threaten national security.

Ultimately, they must consider whether “peace is more risky than war.” As they and others investigate religion as the answer, then communism, democracy, socialism, and war as the “answer,” they must also consider whether negotiation with the great powers, especially America, might lead to peace. Their individual lives, shattered by their arrests and imprisonments, cease to exist in the aftermath of the trauma, and their ability to trust is gone forever.

Mafouz recreates in a mere one hundred pages the historical record of a country yearning to be free at the same time that he depicts the movements against individual freedom which are at their peak. The young people he creates here are ordinary college students, despite the fact that all of them have overcome far more than the average western college stu dent will ever dream of, and though they insist that they still believe in the future of the revolution of 1952, their experience less than fifteen years later, shows them and the reader just how far they have left to go. Dynamic, powerful, and thought-provoking, this novella carries a punch—and modern relevance–that the reader will not soon forget. (On the Favorites List for 2008)

dent will ever dream of, and though they insist that they still believe in the future of the revolution of 1952, their experience less than fifteen years later, shows them and the reader just how far they have left to go. Dynamic, powerful, and thought-provoking, this novella carries a punch—and modern relevance–that the reader will not soon forget. (On the Favorites List for 2008)

ALSO: THE DAY THE LEADER WAS KILLED, THE MIRAGE,

CAIRO MODERN, IN THE TIME OF LOVE

Notes: Many other novels by Naguib Mahfouz are reviewed on this site. See Authors tab at the top of the Home page. http://marywhipplereviews.com/authors/

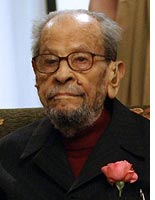

The author’s photo appears on http://www.slate.com

The photo of tanks, under Gamal Abdel Nasser, overthrowing King Farouk in 1952 appear on http://mbouffant.blogspot.com

Nasser’s photo appears on http://www.thefamouspeople.com

The photo of Egyptian POWs, captured by the Israelis during the Six Day War, appears on http://egyptianpows.net