“When I was a girl, I was told that if I misbehaved, the man with the sack would come for me. All disobedient children disappeared into that wicked old man’s bottomless dark sack. But rather than frighten me, the story piqued my curiosity. I secretly wanted to meet the man, open his sack climb into it, see the disappeared children, and get to the heart of the terrible mystery.”

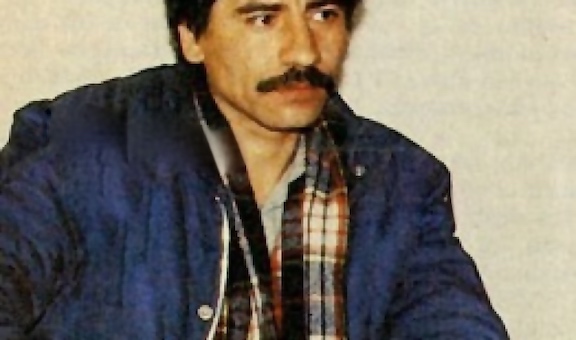

The na rrator of The Twilight Zone, Nona Fernández’s latest novel, admits to having been transfixed as a child by a man who was a soldier, torturer, murderer, and willing supporter of a military regime that repressed all dissent. She had seen his picture on the cover of the magazine Cauce on August 27, 1984, when she was thirteen, a magazine that “belonged to everybody, passed from hand to hand among my classmates.” The testimonies of victims and their families were accompanied by diagrams and drawings that “looked like something out of a book from the Middle Ages,” and the speaker admits that she often dreamed about this soldier-murderer, haunted and perplexed by his story of making people disappear. An intelligence agent for the Chilean military during the presidency of Augusto Pinochet (1974 – 1990), the soldier finally reached his breaking point, unable to withstand the horrors of his job any longer. Presenting himself to a reporter for Cauce, he told his story in “pages and pages of details about what he had done, including names, descriptions of torture methods, and accounts of his many missions.” To the thirteen-year-old narrator, “He didn’t seem like a monster or an evil giant, or some psychopath…The man who tortured people could have been anybody. Even our teacher.”

rrator of The Twilight Zone, Nona Fernández’s latest novel, admits to having been transfixed as a child by a man who was a soldier, torturer, murderer, and willing supporter of a military regime that repressed all dissent. She had seen his picture on the cover of the magazine Cauce on August 27, 1984, when she was thirteen, a magazine that “belonged to everybody, passed from hand to hand among my classmates.” The testimonies of victims and their families were accompanied by diagrams and drawings that “looked like something out of a book from the Middle Ages,” and the speaker admits that she often dreamed about this soldier-murderer, haunted and perplexed by his story of making people disappear. An intelligence agent for the Chilean military during the presidency of Augusto Pinochet (1974 – 1990), the soldier finally reached his breaking point, unable to withstand the horrors of his job any longer. Presenting himself to a reporter for Cauce, he told his story in “pages and pages of details about what he had done, including names, descriptions of torture methods, and accounts of his many missions.” To the thirteen-year-old narrator, “He didn’t seem like a monster or an evil giant, or some psychopath…The man who tortured people could have been anybody. Even our teacher.”

Twenty-five years later, when the former student is working as a scriptwriter for a television series, she “re-enter[s] that dark zone.” The people with whom she is working on a documentary have managed to secure an interview with “the man who tortured people” after he secretly reentered the country to appear in court and present evidence against himself and the rule of Augusto Pinochet, years earlier. This move shocked the French ministers who had been guaranteeing his safety overseas during the intervening years, but he came anyway. The speaker, now an adult, wants to know more about the torturer’s story, one that began over thirty years ago, and she is still wondering whose screams she hears in her head even now, where the images come from, and if there is a “fine line that separates collective dreams?” Finally she imagines writing to him, announcing that she is a woman who wants to “look into the sack” and find out more about his life during Pinochet’s rule, learn how much of that life was forced upon him, and what, if anything, he did because he let himself be persuaded to do so. Confused about whether she would have run away from all the killing if she had been in his place, she imagines him, gives him a face, and decides that he could actually have been her father, uncle, the corner grocer, the mechanic next door, or even her science teacher.

Photo of Andrés Antonio Valenzuela Morales, which appeared on the cover of Cauce, magazine, August 27, 1984

From this point, the novel takes off, circling through time, revisiting long-buried events, recreating the people who lost their lives, and imagining the long-term effects of the crimes. The author herself lived through these times, and it is clear from the feelings she reveals here that she herself knew people who were “disappeared” for their “crimes.” She is also a consummate author, however, always conveying her response to the events from the point of view of the child – and later, teenager – she was at the time when the horrors were part of her daily life. Now, a generation later, she is the mother of a young son, and she still hugs him tight when he leaves for school, “secretly panicked that I might never see him again.” Through this point of view, she reconstructs the Weibel Barahona household of 1976. José Weibel Barahona, a member of the Communist Party, knows he is being watched, and he and his wife are planning to escape from their house and move somewhere else. On the day when they move, they are distracted and don’t see “the man who tortured people.” That man, the soldier Andrés Antonio Valenzuela Morales, is sitting on a bus with them, with a hidden radio transmitter, communicating with vehicles following the bus. When the bus stops, José disappears, one of the approximately three thousand citizens who suddenly vanish forever during this fraught time.

Twilight Zone Col. Adam Cook: Rod Serling’s “Probe 7, Over and Out” introduces us to Colonel Adam Cook, whose spacecraft has crashed into an unknown planet.

One way Fernández brings the young people and the times to plausible life is by including the television programs so popular with the narrator during the times of the horrors. Rod Serling’s “Twilight Zone” is a particular favorite when the speaker is a child, and in her mind, the action on that TV program is as “normal” as the action in her everyday life. The Twilight Zone story of Colonel Cook, a space traveler, is a favorite. Cook “has to make an emergency landing on an unknown planet a million miles from his point of departure.” He has broken bones and cuts, and his spaceship is destroyed. Messages sent home begging for rescue are useless. No one can come save him, and he is alone, now facing the loneliness that makes the “twilight zone” a fearsome fate. In another Twilight Zone episode, a man can change his face whenever he needs to. For those in Chile in the 1970s, he might have been a municipal employee, a peasant, a policeman or a “savage agent,” willing to “torture or turn in his loved ones” – yet another parallel to the realities of life in those times. Even the innocent Smurfs have their day within this highly charged atmosphere of torture and killing.

With the numbers of political horrors building slowly throughout, Nona Fernández creates an unforgettable story of characters who become real for the reader, at the same time that they exist within the context of the speaker’s own youthful life and its aftermath. Much of this novel feels clearly autobiographical, the details of the speaker’s life often emphasizing the ironies in what is happening in the wider world, be it the TV shows from Twilight Zone and Brain Games, or music like the theme song from Ghostbusters, and the Billy Joel song, “We Didn’t Start the Fire.” All but one of the major sections in the novel end with a poetic soliloquy by “the man who tortured people,” Andrés Valenzuela. The last section, however, includes a dark, elegiac letter from the speaker to that man, a dramatic conclusion which suggests that perhaps the narrator, who often appears to be the author herself, is putting her own memories to rest, at last. Or not.

With the numbers of political horrors building slowly throughout, Nona Fernández creates an unforgettable story of characters who become real for the reader, at the same time that they exist within the context of the speaker’s own youthful life and its aftermath. Much of this novel feels clearly autobiographical, the details of the speaker’s life often emphasizing the ironies in what is happening in the wider world, be it the TV shows from Twilight Zone and Brain Games, or music like the theme song from Ghostbusters, and the Billy Joel song, “We Didn’t Start the Fire.” All but one of the major sections in the novel end with a poetic soliloquy by “the man who tortured people,” Andrés Valenzuela. The last section, however, includes a dark, elegiac letter from the speaker to that man, a dramatic conclusion which suggests that perhaps the narrator, who often appears to be the author herself, is putting her own memories to rest, at last. Or not.

ALSO by Fernandez: SPACE INVADERS

Photos: The photo of Augusto Pinochet, leader of Chile from 1974 – 1990, appears on https://ticotimes.net

Andrés Antonio Valenzuela Morales, “the man who tortured people,” gave his story of regrets to a reporter for Cauce magazine and appeared on the cover: http://www.nerudanobel.info

A particularly memorable episode of Twilight Zone featured Col. Adam Cook: Colonel Adam Cook, whose spacecraft has crashed into an unknown planet, leaving him stranded in space. Rod Serling’s “Probe 7, Over and Out.” http://mylifeintheshadowofthetwilightzone.blogspot.com

The author’s photo is from https://en.wikipedia.org

A red Chevy Chevette features briefly in Space Invaders and again in this novel, as the speaker finds herself riding to school in it with friends after it has been used to transport several people to their deaths. https://www.vwvortex.com