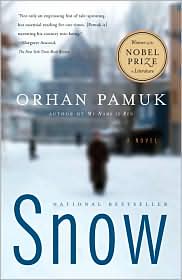

Notes: Orhan Pamuk was WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2006.

“I am proud of the part of me that isn’t European. I’m proud of the things in me that the Europeans find childish, cruel, and primitive. If the Europeans are beautiful, I want to be ugly; if they’re intelligent, I prefer to be stupid; if they’re modern let me stay pure.”

The rich story-telling tradition of the Middle East enlivens Turkish author Orhan Pamuk’s novel about the residents of Kars, a town in the remote northeast corner of Turkey, as Kerim Alakusoglu, known as Ka, returns after many years to investigate a spate of suicides by young women forbidden to wear headscarves in school. Arriving during a blizzard, he feels as if it is “snowing at the end of the world,” and when the city is closed to all traffic for three days, “The desolation and remoteness…hit him with such force that he felt God inside him.”

story-telling tradition of the Middle East enlivens Turkish author Orhan Pamuk’s novel about the residents of Kars, a town in the remote northeast corner of Turkey, as Kerim Alakusoglu, known as Ka, returns after many years to investigate a spate of suicides by young women forbidden to wear headscarves in school. Arriving during a blizzard, he feels as if it is “snowing at the end of the world,” and when the city is closed to all traffic for three days, “The desolation and remoteness…hit him with such force that he felt God inside him.”

Though Kars, which comes from the Turkish word for “snow,” was once a crossroads for trading between Turkey, Soviet Georgia, Armenia, and Iran, all of which are within a few miles of the town, it is now “the poorest and most overlooked corner of Turkey.” All the conflicting political and religious tensions of the country are seen here, its residents representing a melting pot of historical influences—socialism and communism, atheism, political secularism, ethnic nationalism (especially the Kurds), and the most rapidly growing movement, Islamist fundamentalism.

Ka has lived in Frankfurt for the past twelve years and has returned to Turkey only briefly for his mother’s funeral. A poet who has been unable to write anything for the past four years, he learns that Ipek, the woman he has always loved, is now single again and living in Kars. Traveling there ostensibly to interview the families of the “headscarf girls,” he secretly hopes to reconnect with Ipek and make her his wife. As Ka becomes reacquainted with Ipek, he also meets people from the most influential groups in Ka. Ipek’s father, Turgut Bey, is an old communist and atheist, now running the decrepit Snow Palace Hotel, and her sister, the lover of an Islamist militant named Blue, is one of the leaders of the headscarf girls. Ipek’s ex-husband, formerly non-religious, is now running for mayor as an Islamist. Ka’s bodyguards/government investigators tail him everywhere, and the army/police force is a constant presence, but this atmosphere, remarkably, inspires Ka’s creativity, and for the first time in years, he is able to write poetry.

As Ka investigates the girls’ suicides, he is most astonished by their “desperate speed.” Girls and women go about their ordinary lives, and suddenly, without warning, kill themselves. While some officials blame western media for publicizing the suicides, therefore encouraging more girls to kill themselves, the Department of Religious Affairs has plastered the city with “Suicide is Blasphemy” posters, and local Islamists have railed against it. Still the suicides continue, a local official informing Ka that “If unhappiness were a genuine reason for suicide, half the women of Turkey would be killing themselves.”

Other life and death issu es come to the fore when Ka witnesses the coffee shop shooting of the Director of Education, the man who has, on orders from the government, banned the “headscarf girls” from the school campus. The assailant is a young member of the Freedom Fighters for Islamic Justice, and Ka soon meets and comes to know others associated with the movement and the leader responsible for it. The Director has been wearing a tape-recorder, and the reasoned dialogue with which he attempts to communicate with his assailant, and the assailant’s sane, but completely irrational, responses are stunning to a western reader.

es come to the fore when Ka witnesses the coffee shop shooting of the Director of Education, the man who has, on orders from the government, banned the “headscarf girls” from the school campus. The assailant is a young member of the Freedom Fighters for Islamic Justice, and Ka soon meets and comes to know others associated with the movement and the leader responsible for it. The Director has been wearing a tape-recorder, and the reasoned dialogue with which he attempts to communicate with his assailant, and the assailant’s sane, but completely irrational, responses are stunning to a western reader.

Soon afterward, a military coup begins at the National Theater, which is packed to hear Ka read a poem and to see a traveling theatrical troupe perform a modern version of the “headscarf girls” story within the framework of an ancient play. Soldiers burst into the theater, shoot randomly into the audience, which thinks the shots are part of the show, kill a number of people, then round up “dangerous” citizens. Over the next two days, many others are sought, arrested, tortured, and killed, including some of the people Ka has interviewed and visited. Ultimately, as the three-day blizzard ends and Ka readies to leave Kars, Ipek must choose whether to go with him to Frankfurt or to stay in Kars with her family, a decision that is by no means clear-cut.

Different characters here find many different answers and just as many explanations for the underlying problems. As author Pamuk presents their various points of view, the reader finds the novel exploring broad philosophical and intellectual issues almost never tackled in western fiction, in addition to more specific issues related to poverty, modernization, technology, religious doubt, and freedom. The plot is exciting enough to keep a reader who is interested in politics, religion, and philosophy fully and enthusiastically occupied, but readers hoping primarily for an exciting story will find the pace slow as Pamuk explores his themes. The characters are intriguing, but they are more representative of types than individuals.

Many-leveled, beautifully wrought, and complex in its themes, this is a novel which thoughtful western readers will want to explore, a haunting novel rich with insights which should not be ignored. Packed with ironies, black humor, and enough symbols to keep a symbol-hunter busy for days, the novel draws attention to rapidly rising fundamentalist movements and some of the reasons they seek our destruction.

Notes: Also reviewed here: Pamuk’s THE MUSEUM OF INNOCENCE

The author’s photo is from http://www.fullissue.com

Issues of the “headscarf girls” have affected numerous European countries in recent years: http://www.loonwatch.com

The map of Turkey is from http://www.rooms-europe.de/images/mturkey.gif. Kars is in the extreme northeast corner, beside the label for Armenia.