Note: Max Porter was WINNER of the 2016 International Dylan Thomas Prize for Grief is the Thing with Feathers.

“Dead Papa Toothwort wakes from his standing nap…and scrapes off dream dregs of bitten glistening, thick with liquid globs of litter. He lies down to hear hymns of the earth…then he shrinks, cuts himself a mouth with a rusted ring pull and sucks up a wet skin of acid-rich mulch and fruity detrivores. He splits and wobbles, divides and reassembles, coughs up a plastic pot and a petrified condom, briefly pauses as a smashed fiberglass bath stumbles and rips off the mask, feels his face and finds it made of long-buried tannic acid bottles. Victorian rubbish.”

Described in the press release as a “brilliant novel thrum[ming] with anarchic energy,” a “daring [and] ringing defense of creativity [and] spirit,” Lanny, Max Porter’s second novel, is certainly all of that and more, but it is also very different from Max Porter’s prize-winning debut novel, Grief is the Thing With Feathers. That novel focuses on a young father’s challenges after the death of his wife, an intimate and affecting novel about grief which also incorporates some of the imagery associated with author Ted Hughes as he dealt with the death of his own wife, poet Sylvia Plath. Lanny, by contrast, is neither quiet nor reflective. Instead, it explodes with coarse energy, opening with the lead description of Dead Papa Toothwort, an unusual earth spirit who has been hiding below ground for an unknown number of years, waiting for the best moment to reappear on earth. Toothwort, obviously not a gentle, romantic spirit, awakens wanting to “kill things,” then slips through “one grim costume after another as he rustles and trickles his way between trees.” Hiding as part of a tracksuit, a rusted jeep bonnet, and a leather skirt, he pauses, then “plucks a blackbird from the sky, cracks open [its] yellow beak, peers into its ripped face…then flings it across the forest stage,” an image totally different from the first big scene with Crow in Grief is the Thing with Feathers. There Crow appears unexpectedly at the front door of a grieving father and then moves in with the bereaved family to provide emotional help, eventually providing a delightful and memorable learning experience for the family and for the reader.

Described in the press release as a “brilliant novel thrum[ming] with anarchic energy,” a “daring [and] ringing defense of creativity [and] spirit,” Lanny, Max Porter’s second novel, is certainly all of that and more, but it is also very different from Max Porter’s prize-winning debut novel, Grief is the Thing With Feathers. That novel focuses on a young father’s challenges after the death of his wife, an intimate and affecting novel about grief which also incorporates some of the imagery associated with author Ted Hughes as he dealt with the death of his own wife, poet Sylvia Plath. Lanny, by contrast, is neither quiet nor reflective. Instead, it explodes with coarse energy, opening with the lead description of Dead Papa Toothwort, an unusual earth spirit who has been hiding below ground for an unknown number of years, waiting for the best moment to reappear on earth. Toothwort, obviously not a gentle, romantic spirit, awakens wanting to “kill things,” then slips through “one grim costume after another as he rustles and trickles his way between trees.” Hiding as part of a tracksuit, a rusted jeep bonnet, and a leather skirt, he pauses, then “plucks a blackbird from the sky, cracks open [its] yellow beak, peers into its ripped face…then flings it across the forest stage,” an image totally different from the first big scene with Crow in Grief is the Thing with Feathers. There Crow appears unexpectedly at the front door of a grieving father and then moves in with the bereaved family to provide emotional help, eventually providing a delightful and memorable learning experience for the family and for the reader.

Max Porter, winner of the 2016 International Dylan Thomas Prize for Grief is the Thing with Feathers.

Once the spirit of Dead Papa Toothwort appears in Lanny, he then makes himself invisible again and begins to listen to human sounds, an activity which triggers a dramatic change in the formatting of the novel’s text, which suddenly breaks free of all normal constraints. Words and phrases wander free around the page, interrupting ordinary text about Toothwort, and revealing Toothwort’s attention span of only a second or two as wild images and memories appear and just as rapidly change into something else as they move around the page. When he suddenly hears “the lovely sound of his favorite. The boy,” he celebrates, hugging himself “with diseased larch arms…dribbles cuckoo spit down his chin,” and wanders off “tingling with thoughts of how one thing leads to another again and again…with no such thing as an ending.” Operating independently of Toothwort as the story line begins are Lanny’s Mum, an actress and now writer of a violent crime novel; Lanny’s Dad, who works in the city and is rarely at home; and Pete, an elderly artist who is teaching Lanny the basics of drawing. The interactions of these characters with each other and with Lanny soon begin, as changing points of view contribute an operatic tone to the emerging story of Lanny and who he is. Toothwort is foreign to them.

Peggy, a gossip, has seen a listing in the Domesday Book (1086) for Puer Toothwort (Boy Toothwort). “He’s been here as long as there has been a here.”

Part II begins at the halfway point of the novel, by which time the reader is well familiar with the main characters, though never quite sure of what Lanny will or will not do next. A carefree spirit, he seems to have free rein in his activities and in his choice of companions, going where and with whom he wants. Often alone, he listens to his own voices and does not seem to need or want friends – at least not friends of his own age. Though the characters are not named in this section, most readers will find identification of each speaker easy because the author is careful to include clues. When Lanny suddenly disappears, a massive search is started, and the Child Abuse Investigation Unit arrives and sets up an office. Rumors fly. Psychics, fakes, and those who would like to be important all arrive offering to help try to find Lanny, each person wanting to be the “hero of the hour” and each behaving as if he’s “the action star of a soap opera.” Others seem to canonize “St. Lanny, and people who don’t lift a finger for anyone else their whole miserable existence suddenly spring into Search-and-Rescue Save-the-Child-of-Light mode.” In Part III Lanny’s mother, father, and art teacher Pete all receive invitations to a presentation, “Dead Papa Toothwort Presents Lanny: The Ending,” at the village hall. A drawing comes to life, and more than one ending is suggested regarding Lanny.

UK edition.

Those who love fantasy, other worlds, sci-fi, and mythical characters will find much to love in this novel, which maintains its own otherworldly style as the novel progresses. The “rules” of fiction and its long history of development are challenged here, as author Max Porter tries his hand at bending, breaking, and ignoring many old traditions regarding the author and his relationship with his readers. Should a reader expect to share a certain level of involvement in a book of fiction in order to enjoy it? Does the author have any obligation to write for his reader, or is his primary role to set forth his story and his characters and let the result speak for itself? Are there any absolutes regarding the writing of fiction? Porter seems to be challenging our expectations here, writing a novel in which Lanny, the main character, is different and difficult to know or understand from the outset of the novel. Dead Papa Toothwort, the earth spirit, is also different from spirits seen in other novels, and what we are supposed to think of him is not always clear. Is he a “good” or “evil” spirit, or neither, and does it even matter? At times the novel feels as if it is a journal of ideas, instead of a coherent and carefully crafted creation with themes providing unity and a sense of direction. Porter is a brilliant and imaginative thinker, and at his young age, the whole world is his stage. I will be interested in seeing where he goes with his third novel. His debut, Grief is the Thing with Feathers, was on my Favorites List for 2016, and I hope he will return to that more elegant and carefully crafted creative style for his next work.

ALSO reviewed here: GRIEF IS THE THING WITH FEATHERS

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.hayfestival.com

The Domesday Book, in which Peggy found a reference to “Puer Toothwort,” (The Boy Toothwort) suggests that this spirit has been active since the time of the Domesday Book, 1086, almost a thousand years. https://www.ancient.eu

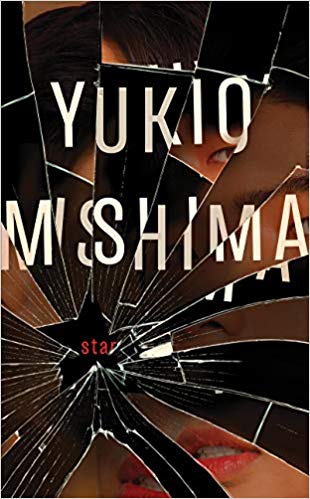

Fans of Yukio Mishima (1925 – 1970) will celebrate this first-ever English translation of Star, one of the thirty-four novels written by Mishima before his death by ritual suicide at age forty-five.

Fans of Yukio Mishima (1925 – 1970) will celebrate this first-ever English translation of Star, one of the thirty-four novels written by Mishima before his death by ritual suicide at age forty-five.

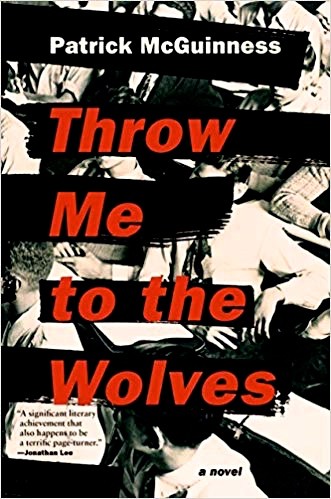

Patrick McGuinness became a favorite when I reviewed his first novel in 2012,

Patrick McGuinness became a favorite when I reviewed his first novel in 2012,

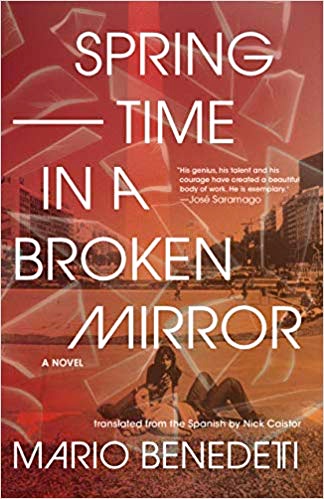

In the years between 1973 and 1981, Uruguay was ruled by the rich and powerful – autocrats who used the power of the military to secure their rule and their continuing wealth – while the needs of the rest of the country were ignored. Idealistic young people and students often talked of challenging this brutal “establishment,” but there was no single leader around to inspire and organize them. As a result, rebellion, if it were to occur at all, would be hit or miss, the private actions of individuals. Journalists often risked their lives to report on news events, student gatherings were monitored, and anyone in the public eye was vulnerable to the whims of those in power. Even the appearance of disloyalty could lead to instant arrest and harsh punishments, including long imprisonments, solitary confinement, immediate exile for a person and his/her family, and even executions – over a dozen a week, on average.

In the years between 1973 and 1981, Uruguay was ruled by the rich and powerful – autocrats who used the power of the military to secure their rule and their continuing wealth – while the needs of the rest of the country were ignored. Idealistic young people and students often talked of challenging this brutal “establishment,” but there was no single leader around to inspire and organize them. As a result, rebellion, if it were to occur at all, would be hit or miss, the private actions of individuals. Journalists often risked their lives to report on news events, student gatherings were monitored, and anyone in the public eye was vulnerable to the whims of those in power. Even the appearance of disloyalty could lead to instant arrest and harsh punishments, including long imprisonments, solitary confinement, immediate exile for a person and his/her family, and even executions – over a dozen a week, on average.

In Optic Nerve, Argentinian author Maria Gainza’s narrator invites the reader into her life to share her love of art – paintings which inspire the glorious feelings which come to her, often suddenly, when she sees something unique in a painting and suddenly connects with it emotionally.

In Optic Nerve, Argentinian author Maria Gainza’s narrator invites the reader into her life to share her love of art – paintings which inspire the glorious feelings which come to her, often suddenly, when she sees something unique in a painting and suddenly connects with it emotionally.