“Everybody talks about genocides around the world, but when the killing is slow and spread over a hundred years, no one notices. Where there are no mass graves, no one notices. American outrage is always for show. It has a shelf life. If that Griffin Book had been Lynched Like Me, America might have looked up from dinner or baseball or whatever they do now.” —Gertrude Penstock

I was a child in Massachusetts when Emmett Till was brutally tortured, mutilated, and ultimately lynched in 1955, but I can still remember vividly when I first heard of his death on radio and TV, and, once I did, I could not “unhear” it. His story was different, so real and so outrageous with its fourteen-year-old victim from Chicago, brutally killed while visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi, that the story would not die for me and my friends. We were close to Emmett Till’s age, we had relatives from out of state whom we enjoyed visiting, and we identified with Emmett, not understanding or believing that just whistling at a white woman was a crime for which he would pay with his life. When we talked about this privately with our parents or among friends at school, we still kept believing that Emmett Till must have done something much more serious that we did not know about. And when the court later found Till’s killers “innocent,” we continued to wonder what he had done that was still kept secret. We youngsters living twenty-five miles from Boston, had never heard of such horrors – or such punishments – being imposed on children.

I was a child in Massachusetts when Emmett Till was brutally tortured, mutilated, and ultimately lynched in 1955, but I can still remember vividly when I first heard of his death on radio and TV, and, once I did, I could not “unhear” it. His story was different, so real and so outrageous with its fourteen-year-old victim from Chicago, brutally killed while visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi, that the story would not die for me and my friends. We were close to Emmett Till’s age, we had relatives from out of state whom we enjoyed visiting, and we identified with Emmett, not understanding or believing that just whistling at a white woman was a crime for which he would pay with his life. When we talked about this privately with our parents or among friends at school, we still kept believing that Emmett Till must have done something much more serious that we did not know about. And when the court later found Till’s killers “innocent,” we continued to wonder what he had done that was still kept secret. We youngsters living twenty-five miles from Boston, had never heard of such horrors – or such punishments – being imposed on children.

Now, sixty-six years after Emmett Till’s lynching, there may be readers who pick up this book without knowing anything about his death, and though Till’s sad story undergirds all the action here, the novel’s narrative and its themes are far broader than the death of one person, however horrible that was. In revisiting this racial crime, Percival Everett pays special attention to the long-term effects of the Emmet Till crime on the people who participated in it, their families, the society in which they lived and shared their beliefs, and the changes, if any, that have occurred since then. He does, however, also add new characters to expand the real story line and make their limited lives more relatable, their problems and difficulties more obvious, and any hopes for the future more sensitive to the visions of the nation’s founders for an effective democracy. Opening in Money, Mississippi, he introduces Wheat Bryant and his wife Charlene who are having a family get-together. Wheat has had only one job in his life, a job he lost when he drove a truck off the Tallahatchie Bridge and then emerged from the wreck clutching a can of beer in his fist. His mother, Granny C., an elderly, deaf woman nearing the end of her life, is sitting quietly, revisiting her past and regretting some of her actions. Her brother J. W. Milam, known as Junior, is also there, along with his son Junior Junior. All are white and uneducated, speak pidgin English, have few, if any goals in life, and excel in their use of profane language and racial epithets. Most importantly, all of them were involved in real crimes against Emmett Till.

A few pages later, Sheriff Delroy Digby gets word to investigate a death in Small Change, a “suburb” of Money. The victim, horribly mutilated, is Junior Junior Milam, who has just been at the get-together. A small black man found with him is also badly beaten, both so damaged that Coroner Reverend Cad Fondle does not even touch them in declaring them dead. Within minutes the black body has vanished from the morgue where it was placed, and no one knows where, when, or how it disappeared, the coroner declaring that it was “the devil hisself” which had claimed it. While the local police are investigating, two black detectives from the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation in Hattiesburg arrive at the scene. When Wheat Bryant is also found dead soon afterward, he, too, is accompanied by a dead black man, the same dead man found earlier at the scene of Junior Junior Milam’s death. In both murders the damage to the white victims has involved the ugly amputation of the same body part and the use of the black victim to hold it for the police. Once again, the black body disappears. And once again, the Doctor Reverend Fondle is terrified of what it means: “Oh, Gawd Jesus, I knows you have a plan, but us poor White mortals is scared to death down here with this strange n—— you keep sending. Is he an omen, O Lawd, a sign, or is he the devil, and should we dismember him and burn his body right away?” The racial murders continue – and spread to other parts of the country – Illinois, Wyoming, Utah, Minnesota, Indiana – always the same in their detail and always with a mutilated white man accompanied by a black.

Officer Ed Morgan of the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation always stopped at the Lorraine Motel to honor Martin Luther King, who died there. It is now the Civil Rights Museum

Percival Everett, a dark-humored and incisive author, has much to say, and he says it cleverly within his novel, often reversing conventional roles. The best of the detectives here are the black detectives from the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, not the white local police. The white murder victims are always accompanied by a black victim, putting those black murders on a par, though the traditional reaction of the local police has always been to give the white deaths more attention. The disappearances of the black bodies and suggestions of divine intervention raise issues of responsibility on a grander scale, and the mutilation of the white bodies and the seeming involvement of the black victims suggest a kind of vengeance understandable even to the most uneducated whites. Professor Damon Thruff, aided by Mama Z, a “root doctor” over a hundred years old, has been doing research on lynchings for years, resulting in the real names of almost three hundred victims being listed in one section of this book and showing the reader that the extent of these crimes goes way beyond the occasional crime that sometimes hits the news.

Despite his serious subject and its even more serious implications for democracy and racial justice, the author manages to keep a light, often absurd touch, preventing the reader from becoming so overwhelmed by issues that s/he becomes inured to the individual horrors. One technique he uses throughout is to give his characters unexpected names – Herberta Hind, Helvetica Quip, Faggart Muldoon, Pinch Wheyface, and Pick L. Dill, for a few. Ultimately, Everett concludes a point in a wild scene featuring a “former President” in the Oval Office calling for his hairdresser after the death of a Secretary. The Trees is unique – a serious study of a serious problem regarding racial justice presented in a readable and often humorous format. Unforgettable for its subject and its messages.

Also: Another novel dealing with the Emmett Till story is Bernice L. McFadden’s Gathering of Waters

Photos. The Tallahatchie Bridge in Money Mississippi. This wooden bridge was burned during a demonstration and destroyed. https://bridgehunter.com

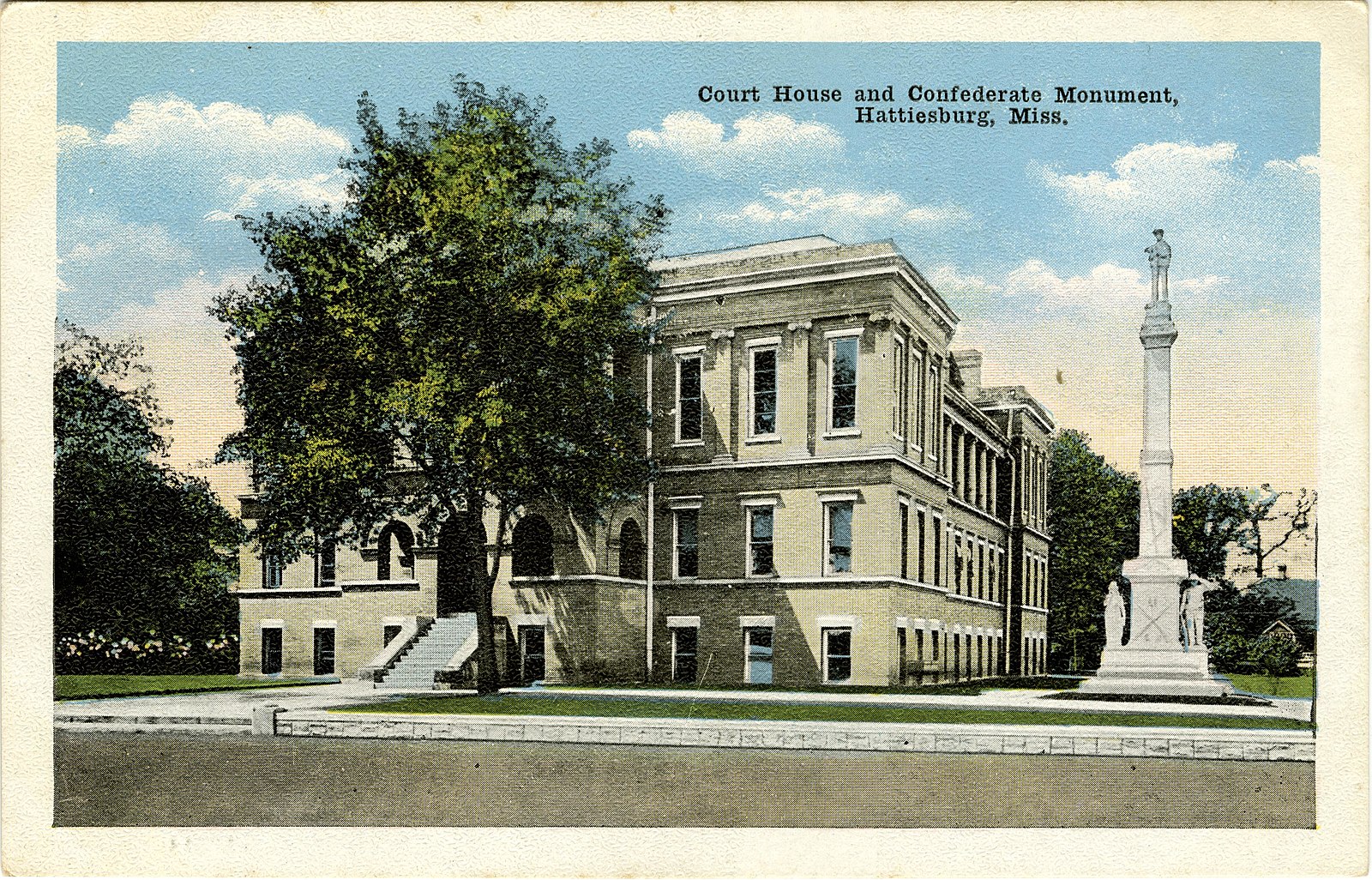

The Court House and Confederate Monument were familiar sites in Hattiesburg for the two Mississippi Bureau Investigation officers. https://commons.wikimedia.org

Officer Ed Morgan of the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation always stopped at the Lorraine Motel to honor Martin Luther King, who died there. It is now the Civil Rights Museum. https://civilrightstrail.com

Percival Everett, author of over thirty books, is a Distinguished Professor of English at USC. https://www.chicagotribune.com