“McSorley’s has the power to transport any of us to whatever New York era feels most like home. That’s because it doesn’t matter if a person first ordered two and two in 1967 or 2000, or if it takes two weeks or thirty years for that customer to come back. Whenever he returns, McSorley’s will be the same.”

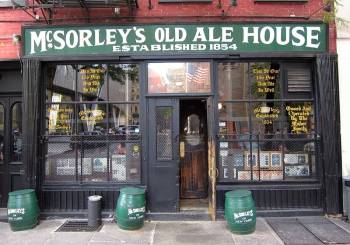

Try, for a moment, to imagine going into the attic of a house occupied by members of your family for one hundred sixty-three years. Old paintings, documents, photographs, small sculptures, war-time hats and helmets, and all manner of other memorabilia fill it from floor to ceiling, and everything there reminds you of the major events which have affected you and those closest to you. Few of us are lucky enough to have such a family attic, but McSorley’s Old Ale House in the East Village of New York City has acquired that status for thousands of customers who have visited it for over a century and a half. Established in 1854 and billed as “the oldest bar in New York city,” McSorley’s, an Irish ale house, serves only dark and light ale, never wine or hard liquor. Owned and operated by only three families during its entire history, McSorley’s has existed continuously at the same location in the East Village since its inception, and many of its employees have been there for decades.

Try, for a moment, to imagine going into the attic of a house occupied by members of your family for one hundred sixty-three years. Old paintings, documents, photographs, small sculptures, war-time hats and helmets, and all manner of other memorabilia fill it from floor to ceiling, and everything there reminds you of the major events which have affected you and those closest to you. Few of us are lucky enough to have such a family attic, but McSorley’s Old Ale House in the East Village of New York City has acquired that status for thousands of customers who have visited it for over a century and a half. Established in 1854 and billed as “the oldest bar in New York city,” McSorley’s, an Irish ale house, serves only dark and light ale, never wine or hard liquor. Owned and operated by only three families during its entire history, McSorley’s has existed continuously at the same location in the East Village since its inception, and many of its employees have been there for decades.

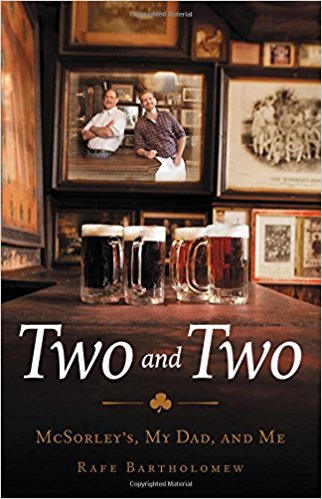

Rafe Bartholomew, the author-son of Geoffrey “Bart” Bartholomew, grew up at McSorley’s, where his father is still working as a bartender after forty-five years. Rafe himself began “working” there for fun when he was five or six, his father often bringing him for a few hours on Saturday mornings to help polish the brass, scrub tables, or clean away the greasy gunk that accumulates around and behind some of the memorabilia. On these Saturdays, Rafe had a chance to hang out with grownups and get to know many of the unusual characters with whom his father worked. When he grew older, he worked there as a casual chef and eventually as a waiter and assistant to his father. He knows McSorley’s from the inside, and as he tells the story of his relationships there, especially with his father, he is also telling the story of a neighborhood gathering place, a culture, and a piece of American history. His background as a journalist and fan of fine writing allows him to communicate directly with a wide readership, and his love and respect for his father and his co-workers make his story of McSorley’s insightful and very real.

Rafe Bartholomew, the author-son of Geoffrey “Bart” Bartholomew, grew up at McSorley’s, where his father is still working as a bartender after forty-five years. Rafe himself began “working” there for fun when he was five or six, his father often bringing him for a few hours on Saturday mornings to help polish the brass, scrub tables, or clean away the greasy gunk that accumulates around and behind some of the memorabilia. On these Saturdays, Rafe had a chance to hang out with grownups and get to know many of the unusual characters with whom his father worked. When he grew older, he worked there as a casual chef and eventually as a waiter and assistant to his father. He knows McSorley’s from the inside, and as he tells the story of his relationships there, especially with his father, he is also telling the story of a neighborhood gathering place, a culture, and a piece of American history. His background as a journalist and fan of fine writing allows him to communicate directly with a wide readership, and his love and respect for his father and his co-workers make his story of McSorley’s insightful and very real.

Both Rafe and his father Bart, who almost became an English teacher, appreciate the McSorley mystique which has attracted famous people from the arts. Poet e. e. cummings wrote a poem about McSorley’s, Dylan Thomas and Eugene O’Neill spent time there, Woody Guthrie sang there in the 1940s, and artist John Sloan painted five scenes of McSorley’s in the years just before World War I. History buffs appreciate the fact that Abraham Lincoln stopped there in 1860 as he was campaigning for office, and an authentic WANTED poster for John Wilkes Booth from April 1865 is displayed on the wall. Houdini left a pair of handcuffs there, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a letter from the White House, and a copy of the Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of Babe Ruth upon his retirement from baseball appears behind the bar. Other photos of John F. Kennedy, Charles Lindbergh, and Alfred E. Newman share a wall with the hats of firemen from 9/11 and helmets from World Wars I and II.

On the right side of the photo, dust-covered wishbones are seen between the gaslights over the bar. Photo by Lee Nelson. Click to enlarge.

One story for which McSorley’s is particularly famous concerns the wishbones that have been hanging on a metal bar connecting two gas lamps for a hundred years. Legend has it that in 1917, just after Thanksgiving, a group of newly enlisted New York soldiers brought their Thanksgiving wishbones to McSorley’s and hung them between the gas lamps for good luck as they left to fight in World War I. After the war the survivors returned and reclaimed their wishbones; many remain unclaimed. Additional wishbones were added during World War II and other US wars. As a sign of respect for all the men whose wishbones became memorials, McSorley’s never allowed them to be disturbed, though dust built up and coated them over the years. In 2010, however, New York City began requiring the annual health inspection of all bars and restaurants in the city. The inspectors, of course, found the wishbones, directly over the bar with their long strings of dust, to be a health hazard. To prevent problems, Matty Maher, the bar’s owner, went to the bar alone at 3:00 a.m. one night to clean each wishbone individually and replace it exactly as it had been, maintaining the feeling of trust, he felt, between the lost soldiers and McSorley’s and preserving them as a lasting memorial, albeit one without dust.

A high point of the book is the strong relationship between Rafe Bartholomew and his dad, a story of love and good humor, especially during Rafe’s mother’s two difficult bouts of cancer, fifteen years apart. The Bartholomews, father and son, returned to their work within a week after she died, discovering that their almost automatic responses to the needs of the job allowed them some respite from their overwhelming sadness. Their care for each other was both touching and memorable, a feeling which they and the rest of the management and staff have also extended to others who live near the ale house, hangers-on and down-and-outers who appear at the door at closing time. Hiring some to work as night watchmen or gofers, and others to do odd jobs that no one else wants, in exchange for $10 – $20, McSorley’s allows these people to earn some money, enjoy a meal, and have the chance to socialize.

Be Good or Be Gone, the motto of McSorley’s. above the icebox. Above the motto by the pipe from the stove, are the handcuffs from Houdini. Click to see more photos.

Despite its many episodes of humor, its quirky personalities, the loving relationship between the Bartholomew father and son, and its revelations about this old ale house, the book does have a down side. Far too much time is spent on descriptions of the men’s bathroom, the difficulties of keeping it clean, the detailing of why sawdust is a feature on all the floors, and the crude comments and language the men make to each other, especially at the beginning. The fact that McSorley’s was a men-only bar until 1970, when it had to be sued before it would admit women, suggests that these details may reflect the stubborn male behavior of many of its patrons, and the learned ability of McSorley’s to tolerate it. Ultimately, I am reminded of a college professor who once said, “The Realists called a spade a spade. The Naturalists called it a goddam shovel.” Realism regarding McSorley’s is a good thing. The shovels of naturalism were unnecessary here.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://sa.kapamilya.com/

The facade of McSorley’s by Leonard J. De Francisci appears on https://commons.wikimedia.org

The bar photo showing the dusty wishbones, by Lee Nelson, may be found on http://www.inetours.com/

The cluttered bar in the front room, with its female bartender, is from http://sideways.nyc/

The picture showing the “Be Good or Be Gone” motto above the icebox is from https://www.6sqft.com A large collection of outstanding photos from McSorley’s appears on this site.

The sign of an excellent bartender at McSorley’s is how many mugs he can carry in his two hands. Here a bartender shows he can carry an amazing twenty mugs. Carrying them is one thing, but the weight of them is something else again! http://bachelor10.com/venue/41/new-york-city/mcsorleys-old-ale-house