“The sun is at the vertical, and shade is as scarce as charity on Biashara Street. Where it exists – shop fronts and alleyways, like cave mouths and canyons – life clings: eyes blink, and patiently they watch. They see a man and a boy walking along the sidewalk, the boy turning every third or fourth step into a skip to match his companion’s rangy stride. Their posture suggests that if either reached out a hand the other would grasp it, but for their own reasons, neither will offer.” Opening scene, Nairobi, Kenya, 2007.

These vibrantly descriptive opening lines introduce a chapter that is a textbook example of good writing, drawing in the reader, establishing an atmosphere, suggesting character, hinting at a father’s relationship with his son, and presenting a familiar scene of a child who can hardly wait for his first bicycle. By the next page, the author has created a much broader, more dramatic context for these characters, expanding the setting, placing this small episode in the context of the larger community, and suggesting ominous new directions for the action. In less than three hundred words, I was hooked. The author’s writing is so confident that I, too, became confident that this debut novel would deliver a well-wrought story with well-developed characters within the fraught atmosphere of Nairobi in 2007, and that it would do so with style and intelligence. It does.

These vibrantly descriptive opening lines introduce a chapter that is a textbook example of good writing, drawing in the reader, establishing an atmosphere, suggesting character, hinting at a father’s relationship with his son, and presenting a familiar scene of a child who can hardly wait for his first bicycle. By the next page, the author has created a much broader, more dramatic context for these characters, expanding the setting, placing this small episode in the context of the larger community, and suggesting ominous new directions for the action. In less than three hundred words, I was hooked. The author’s writing is so confident that I, too, became confident that this debut novel would deliver a well-wrought story with well-developed characters within the fraught atmosphere of Nairobi in 2007, and that it would do so with style and intelligence. It does.

Author Richard Crompton, a former BBC journalist who now lives in Nairobi with his family, understands the city’s social, economic, and political conditions and reveals them through his precise descriptions, his insights into his characters’ motivations, and his appreciation of the tribal loyalties and conflicts which affect virtually every aspect of daily life within this complex society. The main character, forty-two-year-old Police Detective Mollel, has been a national hero for his selfless actions during one national emergency, but he is now a pariah within the department for challenging his superiors and often expressing his rage at the lack of “justice” he sees in society. Otieno, the police superintendent, has even threatened to get rid of him: “Justice is a luxury. Peace is a necessity,” he pronounces. “You want justice, move to some first-world state with sophisticated crime labs and DNA tests and judges who can’t be bought off…Better still, become a judge yourself.”

Mollel, a Maasai within a society dominated by Kikuyu and Luos, is often mocked by his peers for his hanging ear lobes, a tribal tradition which teenage Maasai boys accept as part of their maturation. He is, however, often sought out by other Maasai who do not trust police officers from other tribes. Mollel’s immediate assignment is to investigate the death of Lucy, a young Maasai woman, thought to have been a prostitute, whose bloody body is found in a sewer which extends from Uhuru Park, the huge central park in Nairobi, to Orpheus House, a decrepit, former refuge for prostitutes, now owned by the megachurch of George Nalo Ministries. When Mollel learns from witnesses that the park has been used recently for night-time drills by a paramilitary group just days before the 2007 election, he is alarmed. President Mwai Kibaki, a Kikuyu, is unpopular, and his opponent, Raila Odinga, supported by the Orange Democratic Movement and the Luos is widely expected to win the popular vote – unless it is stolen by thugs from the General Service Unit working for the President and his Kikuyu supporters.

As Mollel investigates Lucy’s murder with the help of her friend Honey, also a prostitute and also Maasai, his own family relationships unfold. Mollel is a loner. His father, his younger brother, his mother, and his wife are all “gone,” and his young son often stays with his mother-in-law in the crumbling outskirts of the city as Mollel pursues justice with a ferocious anger. He senses a similar rage boiling within the city as the prospects of a “stolen” election grow. “Enkai Nanyokie, The [Maasai] Red God, [is] vengeful and capricious, full of jealousy and wrath,” and the Maasai believe that “The Hour of the Red God is a time when madness descends. When people turn against each other and when anger is the only human instinct.” Mollel sees that Hour coming.

Violence breaks out after the 2007 elections in Kenya. Over 1200 people are killed. Photo by Roberto Schmidt/AFP

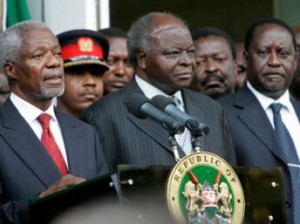

As Mollel has warned (and as historians already know), the Kenyan elections of 2007 are filled with unimaginable brutality which kills over twelve hundred people. As voting day approaches, all available police are assigned to polling places to act as “peace-keepers.” Stores are empty of supplies, since the populace knows that they may not be able to leave their houses for days, and police, like Mollel, never know where the next fire and bloodshed will take place. Many police are seriously injured, all are worried about their own families, and all fear the worst. At the same time, the novel’s other threads, including the murder investigation of Lucy and the possible involvement of the leaders of the megachurch, continue.

UN Sec. General Kofi Annan (L) brokered an agreement between President Mwai Kibaki (C) and Raila Odinga (R), in which Odinga became Prime Minister, thereby ending the violence after the disputed election of 2007.

In the last third of the novel, the action sometimes loses its way, overcome by the sheer density of events. Occasionally, an unnecessary scene will intrude: As a group of tourists leaves their safari for the airport in a truck which Mollel accompanies, the author veers into the clichés of the “ugly tourist,” which add nothing new to the novel. The tourists make patronizing statements, like “You have to expect this sort of thing in Africa…tribal tensions are never very far from the surface,” “All the aid we give them is part of the problem. If you treat people like children, you can’t be surprised when the throw their rattle out of the stroller,” and “They are children, really…I sometimes think they’d be better off if the modern world just left them alone in their mud huts.” Visions of the future, expressed by one African character, offer an easy transition into the action to come, and twists and surprises at the conclusion resolve the action neatly, though sometimes through unrealistic coincidences.

Kawangware, one of the largest slums in Nairobi, is the area where Mollel’s mother-in-law lives, though she claims differently. This area is now the subject of work by a foundation for children and youth, the Lee Oneness Foundation. Please see credits.

Still, this outstanding debut novel, while not perfect, wonderfully depicts the various cultures of Nairobi and its social issues, in addition to some of its legends and beliefs. The novel moves quickly in prose which is often stunning with its imagery, and Mollel, as a main character, never ceases to be intriguing and often unpredictable in his actions. The book’s cover calls this “A Detective Mollel Novel,” suggesting that this is the first of a series. Thoughtful and engrossing, this novel of modern Nairobi and its people is sure to gain fans for any succeeding novels to follow. I will be one of the first in line.

ALSO by Crompton: HELL’S GATE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.telegraph.co.uk

A young Maasai, with his elongated ear lobes, shows one ear with decorations and one folded up. Photo by Hilary Wheeler at http://www.wanderlust.co.uk/

The Kajiado Plain between Nairobi and the Tanzanian border may be seen here: http://www.distancebetweencities.net

Post election violence in Nairobi is photographed by Roberto Schmidt/AFP for http://www.theguardian.com/

Following the disputed 2007 election, UN Sec. Gen. Kofi Annan brokered an arrangement whereby Mwai Kibaki, the incumbent President, remained in office as President, and Raila Odinga, whose Luo supporters believe he won the election, became Prime Minister. The photo appears on http://blogg.fn.no/2013/04

In Kawangware, the Lee Oneness Foundation for Kawangware Street Children and Youth works to help children. Over 400,000 people here, 65% of them children, live on less than a dollar a day. I hope you will read the story of this group’s efforts to provide clean water for the area. http://www.leeonenessfoundation.com/projects/kawangware

ARC: Picador