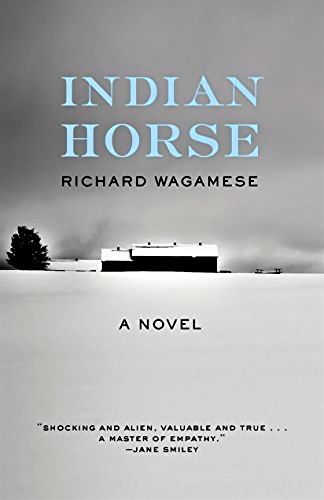

Note: This novel was WINNER 2013 Burt Award for First Nations, Metis and Inuit Literature, and was SHORTLISTED for the International Dublin Literary Award.

“They say that our cheekbones are cut from those granite ridges that rise above our homeland. They say that the deep brown of our eyes seeped out of the fecund earth that surrounds the lakes and marshes. The Old Ones say that our long straight hair comes from the waving grasses of our bays…”

Saul Indian H orse, who tells this story of his life as an Ojibwe living in a non-native society, is in his thirties as the novel opens, and he is at the New Dawn Center, an alcohol rehabilitation facility to which he has been sent by social workers at the hospital where he has been a patient for six weeks. Now alcohol-free for thirty days, he admits that “My body feels stronger. My head is clear. I eat heartily.” Now it is time for his hardest work to begin. “If we want to live at peace with ourselves, we need to tell our stories,” the counselor says, a task Saul decides to address in writing. By writing, he hopes he will regain the gift which he has “spent [his] entire life on a trek to rediscover.” As the reader joins him on this trek, the reader, too, participates in his rediscovery, learning new ways of seeing and thinking and expanding the visions of the natural world which have slowly died for so many by the end of the twentieth century. The result is a book unique in its perspective and its “cure.”

orse, who tells this story of his life as an Ojibwe living in a non-native society, is in his thirties as the novel opens, and he is at the New Dawn Center, an alcohol rehabilitation facility to which he has been sent by social workers at the hospital where he has been a patient for six weeks. Now alcohol-free for thirty days, he admits that “My body feels stronger. My head is clear. I eat heartily.” Now it is time for his hardest work to begin. “If we want to live at peace with ourselves, we need to tell our stories,” the counselor says, a task Saul decides to address in writing. By writing, he hopes he will regain the gift which he has “spent [his] entire life on a trek to rediscover.” As the reader joins him on this trek, the reader, too, participates in his rediscovery, learning new ways of seeing and thinking and expanding the visions of the natural world which have slowly died for so many by the end of the twentieth century. The result is a book unique in its perspective and its “cure.”

Saul is just four years old in 1957, when his nine-year-old brother Benjamin disappears. His sister vanished five years before. These kidnappings are all part of a brutal program to separate aboriginal children from their families and their culture, send them to a school where they will live apart from everything and everyone they ever knew, and teach them English and the Canadian school curriculum. Ultimately, the goal is to turn them all into “Canadians,” without connections to their aboriginal past. With Benjamin’s’s disappearance, Saul’s mother has a complete breakdown, and when Saul’s father and uncle paddle downriver to sell berries, they return, “bringing the white man with them in brown bottles.” His parents grow to depend on these “spirits,” and when Benjamin, their “lost” son, finally manages to run away from the school and walk sixty miles to find them, three years later, he is thin, with a terrible cough – tuberculosis caught at “the school,” which will soon cost him his life. Benjamin’s death, the alcoholism of the parents, and the lack of the family’s traditional cultural values spell the end of the family. Before long, Saul too, is captured and enrolled at St. Jerome’s Indian Residential School.

Author Richard Wagamese, himself a member of the Objibwe tribe, details the grim lives of the abused young children forced to live in these schools. While he himself was not part of this schooling program, his parents were. He ended up in foster care instead, the schools’ equivalent. Here he suffered beatings and abuse which were no different from the depiction here of the beatings and abuse at St. Jerome’s, all inspired by the national desire to wipe out native cultures and assimilate the residents into the Canadian mainstream. At St. Jerome’s young children are beaten and confined to a small box in the basement called “the Iron Sister” for such crimes as wetting their beds. As Saul says, “I saw kids die of tuberculosis, influenza, pneumonia, and broken hearts. I saw runaways carried back, frozen solid as boards. I saw wrists slashed and, one time, a young boy impaled on the tines of a pitchfork that he’d shoved through himself.” These children universally yearn for the freedom to be outdoors in nature, sharing the spirits of the earth and sky which have been so much a part of them until now.

Reggie Leach, of Ojibwe ancestry, made his hockey debut in 1971 with the Boston Bruins during the Bobby Orr era, then continued his career with the Philadelphia Flyers.

Fortunately, Saul Indian Horse is able to find some salvation. St. Jerome’s has a hockey team, and he, at age eight, is desperate to be part of it, though he has never played. By volunteering to shovel off the ice on the outdoor rink every morning, he is able to be outside, early and alone, and he soon finds a hockey stick, which he hides, and some skates which he stuffs with straw so they fit, so that he can practice on the rink when no one is up. For Saul, hockey becomes the equivalent of a natural religion. On the ice, he can feel the wind and the air, and he can imagine where the openings are as he skates through the “opposition” and then “passes” to a teammate. He can “see” the results long before they actually happen. When he begins to play on a team, his reputation as a hockey player grows quickly. Unfortunately, because of his excellence on the ice, the fact that he is two or three years younger than other players, and is still very small, he is constantly bullied. Eventually, Saul becomes the foster child of an Ojibwe family in which the father is a coach for an important youth team. From there, he goes on to success in the competitive hockey leagues, some of them associated with the National Hockey League. The bullying and name-calling over his heritage continue, however, no matter how hard he plays or how good he becomes, and he ultimately ends up at the New Dawn Center for Alcohol Rehabilitation in search of a new direction, new goals.

Author Richard Wagamese has dedicated his writing career to recreating the values and joys of aboriginal life, along with its problems, including the innate resentment felt by many “outsiders” toward those whose goals and ways of life may be different. As someone who has never played hockey, I never knew how liberating it might feel to be on the ice in total control, almost in a trance in which the game unfolds in one’s mind before it even begins to happen on the ice. To have control over the action and to make it happen is described so powerfully here that I suddenly understood why, for Saul, hockey becomes the equivalent of a religious experience – one not unlike being in a trance, in the power of an outside force. When Saul ultimately returns to God’s Lake, his family’s holiest place, deep in the Canadian bush, for affirmation of his plans, the reader understands, and when Saul returns to try out his newly resolved life in the city where he lives, the reader easily imagines him in “the white glory of a rink.”

ALSO by Wagamese: MEDICINE WALK and STARLIGHT

Photos. St. Jerome’s Residential School in White River Ontario. http://jordangrade11english.blogspot.com

Gods Lake, the sacred place for Saul Indian Horse and his family. https://www.winnipegfreepress.com

Reggie Leach, of Ojibwe ancestry, made his hockey debut in 1971 with the Boston Bruins and Bobby Orr, then continued his career with the Philadelphia Flyers. He now works with indigenous youth. https://www.ebay.com

Author Richard Wagamese, holding the symbolic eagle feathers: https://www.theglobeandmail.com

Reggie Leach, now in retirement. He is a motivational speaker and worker with indigenous youth: https://brocku.ca/