“When the author is in the middle of writing [a novel], the end can’t be the most important thing, and many times it is hasn’t even been determined. What matters is the active participation of the reader, concurrent with the act of writing. Bolano makes this very clear in his explanation of the title: ‘The policeman is the reader who tries in vain to decipher this wretched novel.’ ”—Juan Antonio Masoliver Rodenas, author of this novel’s “Prologue: Between the Abyss and Misfortune.”

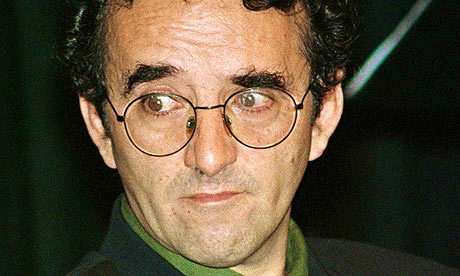

Many readers will argue that this work is not a novel at all. Certainly it does not adhere to the traditional expectations of a novel, no matter how flexible the reader is with definitions. Begun at the end of the 1980s and still unfinished at the time of author Roberto Bolano’s death in 2003, at the age of fifty, The Woes of the True Policeman was always a work in progress, one on which the author continued to work for fifteen years. Many parts of it, including some of the characters, eventually found their way into other works by Bolano, specifically, The Savage Detectives and his monumental 2666. But though it is “an unfinished novel, [it is] not an incomplete one,” according to the author of the Prologue, “because what mattered to its author was working on it, not completing it…Reality as it was understood until the nineteenth century has been replaced as reference point [here] by a visionary, oneiric, fevered, fragmentary, and even provisional form of writing.”

Many readers will argue that this work is not a novel at all. Certainly it does not adhere to the traditional expectations of a novel, no matter how flexible the reader is with definitions. Begun at the end of the 1980s and still unfinished at the time of author Roberto Bolano’s death in 2003, at the age of fifty, The Woes of the True Policeman was always a work in progress, one on which the author continued to work for fifteen years. Many parts of it, including some of the characters, eventually found their way into other works by Bolano, specifically, The Savage Detectives and his monumental 2666. But though it is “an unfinished novel, [it is] not an incomplete one,” according to the author of the Prologue, “because what mattered to its author was working on it, not completing it…Reality as it was understood until the nineteenth century has been replaced as reference point [here] by a visionary, oneiric, fevered, fragmentary, and even provisional form of writing.”

Many of the critical reviews of this work stress Bolano’s past successes and his great contributions to Latin American literature and to world literature in general, and most of these reviews begin their discussion of this work with a summary of its plot, suggesting that this work is not too different from other novels. It does, in fact, have some resemblances to a traditional novel, once one gets beyond the first chapter, a commentary about literature in general and poetry in particular. Padilla, a young student and writer, asserts to Amalfitano, his professor, that “Poetry [is] completely homosexual. Within the vast ocean of poetry [are] various currents: faggots, queers, sissies, freaks, butches, fairies, nymphs, and Philenes.” He then proceeds to describe which poets fall into which categories, without clearly differentating the categories. His professor notes, “You missed the category of talking apes.”

Monaldo Leopardi, philosopher and writer, whose "brooding look" reminded Padilla of Mario Vargas Llosa

Beginning in chapter two, Bolano gives background for Padilla, his childhood, his relationship with his father, his tendency to violence, and the writing of his first book of poetry. Before the end of that chapter, Padilla has seduced his fifty-year-old professor, Amalfitano, the widowed father of a teenaged daughter. The next chapter describes a film which Padilla plans to make about Leopardi, the Italian poet, and since he is not going to be able to hire professional actors, he plans to use his friends. Reserving the best role for himself, he plans to ask Mario Vargas Llosa to play the role of Monaldo Leopardi because of his “brooding look,” with other roles being offered to Enrique Vila-Matas, Antonio Munoz Molina, and Javier Marias, among others.

Before long, a whispering campaign regarding Amalfitano endangers his job at the University of Barcelona, and as a result of the scandal involving Padilla, Amalfitano must find another place to teach, outside of Spain. Padilla stays on in Barcelona, writing a novel, The God of Homosexuals, while Amalfitano eventually ends up at the University of Santa Teresa, in a town modeled on Ciudad Juarez on the border of Mexico and Texas. This is the framework of the “plot.”

The action swirls back and forth and around in time, gradually filling in details about Amalfitano’s marriage and his fatherhood, his various jobs in other countries, his changing political points of view, and his favorite poets and novelists. One of his favorites is J. M. G. Arcimboldi, who is discussed in an encyclopedic manner in one thirty-page section of the novel, though he has no real role in the action which takes place. A complete list of the novels and poems of this fictional author is followed by sections entitled, “Two Arcimboldi Novels Read in Five Days,” “Three Arcimboldi Novels Read in Five Days,” “Two Arcimboldi Novels Read in Three Days,” etc., complete with the plot summaries. Arcimboldi’s friendships, his epistolary relationships, his hobbies and training, and his list of enemies complete this section, which may be fascinating to those who have already read The Savage Detectives and 2666, in which Arcimboldi apparently also appears, though the usefulness of this section in this book is a question. Arcimboldi’s disappearance is a side note to the novel.

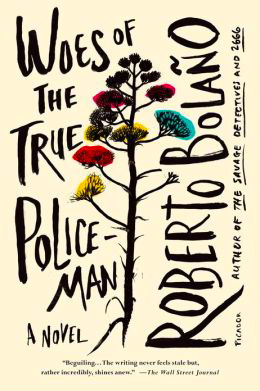

Though Amalfitano maintains a correspondence with former lover Padilla in Barcelona, much of the action in Santa Teresa centers on his new relationship with another young man, Castillo, whom he finds sleeping under a tree one night. Unlike Padilla, who is a writer, Castillo is a painter – or, rather, a forger of paintings by other, well-known painters, especially the pop artist Larry Rivers. Much later in the novel, amidst many other digressions, Amalfitano’s life with former lover Padillo takes on new importance and leads to philosophical discussions about reality and what one may expect to gain from a long life of introspection.

If all this seems wandering and diffuse, it is. As Amalfitano himself has discovered, “The Whole is impossible…Knowledge is the classification of fragments,” and Bolano is leaving it to the reader – his “true policeman” of the title – to figure it all out. Through digressions about the Mexican Revolution and Pancho Villa; the fighting of the Mexicans against the French and Belgians; the love story of Amalfitano’s daughter Rosa; five generations of women named Maria Exposito; identical twins named Pedro and Pablo Negrete, one of whom becomes chief of police and the other of whom becomes a philosophy student; the investigation of Amalfitano by the police; and the succession of political leaders in Santa Teresa, Bolano keeps the reader going, always intrigued, but, in my case, at least, always hoping that all this will somehow provide links to a main theme that will unite it all. Apparently, the main theme is one of disconnection, not only in our lives, but also in our expectations regarding writing and the other arts. As Amalfitano says to himself, “Look over there, dig over there, over there lie traces of truth. In the Great Wilderness… It’s with the pariahs that you’ll find some justification, if not vindication; and if not vindication, then the song, barely a murmur (maybe not voices, maybe only the wind in the branches, but a murmur that cannot be silenced.”

ALSO by Roberto Bolano: THE INSUFFERABLE GAUCHO and THE THIRD REICH

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Bertrand Parres/AFP, Getty, may be found on http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=97691449

The painting of Monaldo Leopardi (1776 – 1847) is from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monaldo_Leopardi

The photo of Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa appears on

http://listas.20minutos.es/

The Larry Rivers painting, and an article about Larry Rivers himself, may be found on

http://www.vincentkatz.com/

The Wanted poster for Pancho Villa (1878 – 1923) is here:

http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/pancho-villa.htm

ARC: Picador