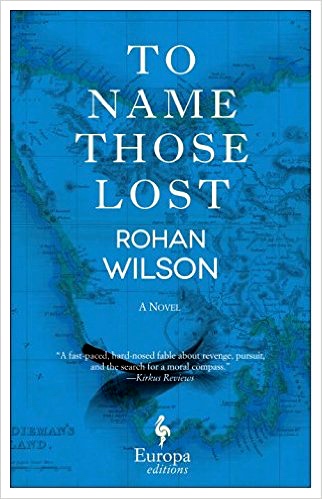

Note: This novel, the author’s second, was WINNER of the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for Best Novel when it was published in Australia in 2015.

“In the early morning dark among the man fern of the damp hill’s foreslope, Toosey unbundled his bedroll and sat watching his backtrack and waiting. He built no fire and took no tea but sat on the blankets peeling a turnip with his knife, passing slices to his lips. A bone-splinter moon rose wondrous within the overspread of stars, the dark below the [gum trees] deepening into blue and then black, but still no one appeared upon the slope. Had he eluded them?” Thomas Toosey, father of William, hiding from pursuers.

In 1874, the island of Tasmania, one hundred fifty miles off the southeast coast of Australia, is boiling with rage. Once a penal colony filled with the hardest criminals, and the site of almost total genocide of the original aboriginal inhabitants by the British, Tasmania, in 1874, is a seething cauldron of hungry men and the toughest of women, many of them homeless, trying to survive the only way they know – by using whatever weapons they have at hand to gain what they need to stay alive. Adding to the problems of the poor, the Launceston and Western Railway Company, run by the colonizers, has recently accumulated large debts at the hands of speculators, and the Tasmanian government has just decided to make its citizens pay for those losses. Learning that the legislature has “voted to confiscate our property, steal our money, and make ruins of our lives,” large crowds gather to take matters into their own hands. “It is because they believe us weak,” they decide. “Because they believe the undue exercise of power over the supine and the insipid is their prerogative.” Resentment against the police is high, and the tempers of the poor and hungry are shorter than short.

In 1874, the island of Tasmania, one hundred fifty miles off the southeast coast of Australia, is boiling with rage. Once a penal colony filled with the hardest criminals, and the site of almost total genocide of the original aboriginal inhabitants by the British, Tasmania, in 1874, is a seething cauldron of hungry men and the toughest of women, many of them homeless, trying to survive the only way they know – by using whatever weapons they have at hand to gain what they need to stay alive. Adding to the problems of the poor, the Launceston and Western Railway Company, run by the colonizers, has recently accumulated large debts at the hands of speculators, and the Tasmanian government has just decided to make its citizens pay for those losses. Learning that the legislature has “voted to confiscate our property, steal our money, and make ruins of our lives,” large crowds gather to take matters into their own hands. “It is because they believe us weak,” they decide. “Because they believe the undue exercise of power over the supine and the insipid is their prerogative.” Resentment against the police is high, and the tempers of the poor and hungry are shorter than short.

Within this fraught atmosphere, Tasmanian author Rohan Wilson introduces several hard men, women, and children who are also dealing with emotionally exhausting personal problems, many of which involve long-standing resentments and hatreds. To accommodate both the general turmoil and the personal traumas of his characters, Wilson creates his own style of gothic novel, a form which allows him to recreate the horrors and abuses of the times while also creating overt sentiment and sympathy for some of the characters. The hero of the novel, if it can be said to have one, is twelve-year-old William Toosey, a street child, who discovers, as the novel opens, that his mother is extremely ill, probably dying. Rushing to find a doctor, whom he cannot afford, he is accosted by the sadistic local constable, Beatty, who refuses to let him pass, demanding information from William about the theft of some cases of beer and, with his junior constable, beating William on back and legs until he can hardly move. By the time William is able to get free and find the doctor, his mother is dead. The doctor does him a “favor,” however, granting him fourteen days to pay his bill. William decides to write to his long-absent father for help.

Within this fraught atmosphere, Tasmanian author Rohan Wilson introduces several hard men, women, and children who are also dealing with emotionally exhausting personal problems, many of which involve long-standing resentments and hatreds. To accommodate both the general turmoil and the personal traumas of his characters, Wilson creates his own style of gothic novel, a form which allows him to recreate the horrors and abuses of the times while also creating overt sentiment and sympathy for some of the characters. The hero of the novel, if it can be said to have one, is twelve-year-old William Toosey, a street child, who discovers, as the novel opens, that his mother is extremely ill, probably dying. Rushing to find a doctor, whom he cannot afford, he is accosted by the sadistic local constable, Beatty, who refuses to let him pass, demanding information from William about the theft of some cases of beer and, with his junior constable, beating William on back and legs until he can hardly move. By the time William is able to get free and find the doctor, his mother is dead. The doctor does him a “favor,” however, granting him fourteen days to pay his bill. William decides to write to his long-absent father for help.

William’s father, Thomas Toosey, has been held incommunicado by a “deadman” who is about to claim the bounty placed on Toosey by Fitheal Flynn, a man whom Toosey has robbed. Flynn and a hooded man soon arrive at the shed where Toosey has been held, but Toosey has managed to escape into the bush. Hardened by his earlier life in Tasmania as a tracker and bounty hunter of the aborigines, Toosey is a killer, seeing “in the bullet, the knife, and the club a power that could make a man his own master,” and at age fifty-nine, he is still using those weapons to make his way in life. Now resting overnight in a cave, he still makes note of the kangaroo mobs and the small flock of rosellas “dipping and swinging and making horrible cries,” a natural but unlikely image ascribed to a man hiding for his life. Determined to “to do right” by his son William, who has written to him for help, Toosey is committed to acting like a real father.

These potoroos, “rat-kangaroos,” are small marsupials, about the size of a rabbit, which hop on their hindfeet and dig for much of their food. Toosey snares one for food while he is in hiding. Photo by Dick Walker.

The action and points of view alternate among William Toosey and the life he is leading after his mother’s death; Thomas Toosey, who is trying to reach his son William from another part of the island so he can help him; Fitheal Flynn and his “hooded man” who are trying to get back the money that Toosey has stolen from them; and Beatty and Webster, the local constables who are trying to capture any and all of them. Additional connections between Toosey and Fitheal Flynn and his hooded accomplice explain why Flynn’s hatred of Toosey is so visceral and unyielding and why he is willing to fight Toosey to the death. One more character, Jane Eleanor Hall, whose head is shaved and is thought, at first, to be a man, adds to the complexities and mysterious identities when she finds Flynn and his companion hiding in her house and offers to help them find Toosey if they pay her for her help.

As in other gothic novels, the action here comes fast and furious, with elaborate descriptions bringing it alive, and violence the usual result of interactions of characters. Interestingly, the “hero” here, young William Toosey, and the anti-hero, Thomas Toosey, are from the same family and have some love for each other, adding a humanizing, if not sentimental, touch. Toosey and Flynn, both bearing true hatred for each other, are fated to meet each other in a showdown, the outcome of which should require that both end up dead. Their place in the universe of violence which surrounds them, however, makes their fates seem less important than it is in most Victorian gothic novels, as their young accomplices, William Toosey and Flynn’s hooded mystery man would seem to have little future without them. At one point, a melodramatic pronouncement adds a bit of moralizing to the novel: “The sound of love is to name those lost who lived for others,” the source of the novel’s title.

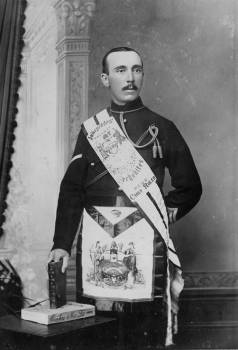

Rechabite man in his sash and elaborate dress, a vastly different appearance from the dirty and tattered clothing of the local men.

Within all the misery here, Wilson does include one darkly humorous “take” on religion, unlike traditional gothic novels in which good, evil, and a genuine sense of a god and/or a devil pervade the action: At one point, Flynn and his exhausted and hungry accomplice, are waiting for a train when representatives of the Independent Order of Rechabites, a temperance group, elaborately dressed and holding ornate banners, leave the train to the beat of drums. The contrast with the rest of the waiting crowd leads Flynn to exclaim, “What in the name of fock…For the love of God, would you look at them,” clearly an indication that this Tasmanian gothic novel differs from traditional British gothic in important ways.

ALSO by Rohan Wilson: THE ROVING PARTY

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://freshfiction.com

Toosey, while hiding from pursuers, comments on the presence of kangaroo mobs and rosella birds. http://pixdaus.com

The potoroo, or rat-kangaroo, is a rabbit-sized marsupial which hops on its hind feet and digs for much of its food. Toosey snared one of these while in hiding and expected to use it for food. http://www.potoroo.org/

The bulldog pistol, often worn hidden behind the back of Flynn’s hooded accomplice, plays an important role throughout the novel. http://www.armeancienne.fr/

Men wearing the clothing of the Independent Orders of Rechabites get off the train as the locals are waiting. Representing a tee-totalling, religious existence, they are an ironic contrast with the local men in their dirty and tattered clothing many of whom are drunk. http://www.soldiersofthequeen.com