“There is no tomorrow without yesterday.”

Heaven’s Edge is unique–it is not a romance, not a war chronicle, not a religious allegory, not a plea for ecological responsibility, and not science fiction, though it contains elements of all these genres. Marc, a young college graduate from London, has returned to an unnamed island, much like the author’s island of Sri Lanka, on a mission to connect with his father’s memory. His father, a military pilot, left the family in England when Marc was a very young child and returned to the island where he died while on a mission. Marc’s doting grandfather, who raised him, never understood what drove his son to return to the very island he himself had escaped.

Edge is unique–it is not a romance, not a war chronicle, not a religious allegory, not a plea for ecological responsibility, and not science fiction, though it contains elements of all these genres. Marc, a young college graduate from London, has returned to an unnamed island, much like the author’s island of Sri Lanka, on a mission to connect with his father’s memory. His father, a military pilot, left the family in England when Marc was a very young child and returned to the island where he died while on a mission. Marc’s doting grandfather, who raised him, never understood what drove his son to return to the very island he himself had escaped.

The novel opens with Marc’s arrival at the island by boat, and Gunesekera quickly establishes the mood and the themes of freedom and repression, and past and present, as the boatman, upon his arrival, releases two flying fish, accidentally netted during the trip. The island is under military control, and the hotel where Marc stays strictly limits his movements.

In an intensely romantic scene, Marc escapes the stultifying restrictions one day and meets Uva, a young woman who is trying to repopulate the forest with native birds and animals, all of which have disappeared during the long war. When Marc is suddenly rendered unconscious and Uva disappears from his life, the mood changes instantly from romance to surreality, as Marc finds himself in captivity, enduring a regimented life more akin to science fiction than the heights of romance.

Mind-numbing violence, brutally perpetrated by the military to remove any question of free thought and independent activity in the population, is the only constant in the lives of the characters, as Gunesekera explores our need to remain connected to our pasts and the ways in which our futures are outgrowths of our pasts. The graphically described violence further sets into sharp relief themes of personal identity, the desire for beauty, and the need to protect and preserve the natural world.

Sometimes enigmatic and even a bit preachy, the novel is at once magical and nightmarish, full of myth and allegory at the same time that it offers haunting, cautionary tales about the past and the use of violence to change the present and affect the future. Echoes of Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden, the fall of man, legends about peacocks and leopards, and episodes telling the importance of love and respect pervade the novel, giving it immense color and depth. Clearly a pacifist, Gunesekera says, “The art of killing cannot be our finest achievement…Nothing is inevitable.”

Sometimes enigmatic and even a bit preachy, the novel is at once magical and nightmarish, full of myth and allegory at the same time that it offers haunting, cautionary tales about the past and the use of violence to change the present and affect the future. Echoes of Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden, the fall of man, legends about peacocks and leopards, and episodes telling the importance of love and respect pervade the novel, giving it immense color and depth. Clearly a pacifist, Gunesekera says, “The art of killing cannot be our finest achievement…Nothing is inevitable.”

But Gunesekera does not believe in being completely passive or non-violent when faced with true threats to life. “Sometimes you have to sacrifice your innocence to protect this world,” he says. In this memorable novel with its stunning depictions of nature, especially birds and butterflies as they try to survive the depredations of man, he makes a powerful, ecological and political statement, presenting characters who try to create gardens of their own out of the decimated gardens of their pasts.

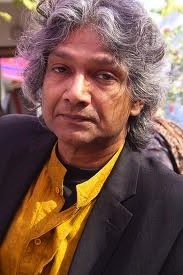

Notes: The author’s photo appears on http://thedelhiwalla.blogspot.com

Forest scene in Sri Lanka: http://withanage.tripod.com