Note: Canadian author Ross King is a three-time WINNER of the Governor General’s Award, the highest literary award in Canada, for Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling (2003), The Judgment of Paris: the Revolutionary Decade that Gave the World Impressionism (2006), and Leonardo and the Last Supper (2012).

“Painters of water [like Claude Monet] usually concentrated on more distant effects, such as moonlight shimmering on ruffled rivers or waves crashing heavily on the beach. Monet himself was an acknowledged master of these sorts of waterscapes…But Monet beside his lily pond was in search of more intimate impressions as he registered not only the surface vegetation and reflections but also the water’s murky, half-hidden depths.”

Claude Monet (1840 – 1926) was already recognized as one of the most important impressionist painters in the world by the time this study of his work begins in 1914. At seventy-four, he still worked outdoors, painting in his garden at Giverny, his rural home forty miles northwest of Paris. He was impatient to keep working, with many more paintings to go, many more milestones to reach. The word “impressionistic,” a pejorative term when it was first applied to the work of Monet and others at their group exhibition in Paris in 1874, refers to their seemingly spontaneous and unstructured style, a marked contrast to the smooth, elegantly formal paintings of the Salon of Paris, the official style of the French Academie des Beaux Arts. The impressionists’ light-filled paintings and their ability to achieve a new depth and immediacy in their work by superimposing colors upon colors in short brush strokes, gradually won over patrons, and over the next twenty-five years, artists like Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, and Mary Cassatt became both famous and successful.

Author Ross King as he receives the Canada’s Governor General’s Award in 2012 for LEONARDO AND THE LAST SUPPER.

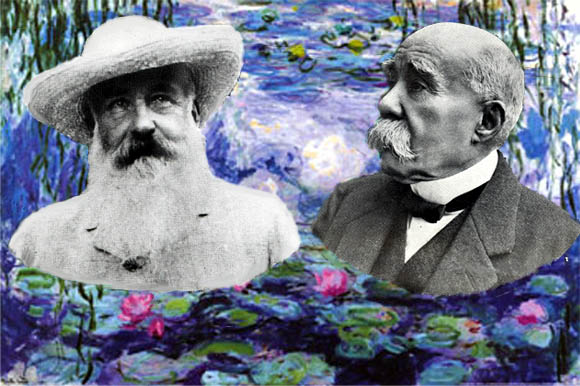

Among Monet’s closest friends was Georges Clemenceau, a former Prime Minister of France, leader of the Radical Party, medical doctor, journalist, novelist, art lover, supporter of Alfred Dreyfus, and, not incidentally, lover of gardening who lived within twenty miles of Claude Monet. Skilled at negotiating on a professional level, Clemenceau was one of the few people who could “get through” to the stubborn and uncompromising Monet when Monet became impatient with the progress of his work and, later, the status of his eyesight. It is Clemenceau’s presence throughout this book which provides a clear perspective on the life and work of Monet and its place within the life of a country at war against Germany from 1914 – 1918. The ironic image of Monet, taking an underground passage every day to his private garden so that he could paint his roses, water lilies, and weeping willows while the Battle of Verdun was going on just two hundred miles away, provides a perspective on Monet’s artistic commitments and their contrast with the work of Clemenceau, who was Minister of War.

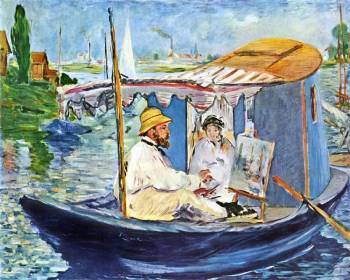

Besides Clemenceau, Monet was fortunate throughout his life to have a number of other people dedicated to his welfare. His first wife, Camille, by whom he had two children, sometimes accompanied him on his studio-boat, where he could paint while observing the changes in the water’s surface, along with the ambient light, color, sky, and shadows. After Camille died at age thirty-two, Monet began a long affair (and later marriage) with Alice Hoschede, an artist married to a man who had been one of Monet’s patrons. When Alice died in 1911, her daughter Blanche, who married Monet’s son Jean, became Monet’s caregiver and assistant. Other loyal friends were Gustave Geffroy, a journalist, art critic, and novelist, who was also a friend of Clemenceau, and Sacha Guitry, an actor, director, and playwright, who was a generation younger than Monet, but whom Monet regarded as “a delightful friend.” These characters appear and reappear through the book as they offer council and often try to cheer the often impatient and frustrated Monet.

Edouard Manet portrays Monet and first wife Clarisse in Monet’s boat- studio, ca. 1874. Click to enlarge.

As Monet aged, his work became more abstract, and his water lily paintings, done very late in his career, are not only his biggest, but, many critics believe, his best paintings. In 1909, he had told a friend from Paris, Raymond Koechlin, a wealthy and cultured patron, that he would like to install “a flowery aquarium in a domestic setting to provide a tranquil oasis.” The primary motif he had in mind was of water lilies from his own water-garden, which he had painted occasionally in the past, and when Koechlin visited him again in 1914 and asked about this project, Monet said that he was, in fact, beginning to work on this idea, though “he felt ashamed to be painting when so many people were suffering and dying.” Recognizing that “moping changes nothing,” however, Monet admits to Koechlin, “I’m pursuing my idea of a Grande Decoration,” a project that would consume the rest of his life.

One of Monet’s “upside down” paintings with the sky at the bottom as a reflection. This also shows the weeping willows upside down. Click to enlarge and to see many more closeups of Monet paintings.

Building a new studio to accommodate huge canvases – each of which was six-and-a-half feet high by fourteen feet long, Monet would eventually create fourteen separate series incorporating and connecting up to fifty panels. These panels, if combined end to end, would have stretched over seven hundred feet – a Grande Decoration by any measure. Determined to donate some of these to France and its museums, Monet hoped to have some of them displayed in an oval room, where they would be “glued” to the walls to accommodate the curve of the room and create an almost circular view. Eventually, in 1922, he signed a contract to have eight enormous panels installed in the Musee de L’Orangerie in Paris. Though the country expected these to be delivered within a year, circumstances prevented that. Monet had been diagnosed with cataracts in both eyes in 1912, and now, after ten years, his sight was seriously compromised.

Three of Monet’s enormous panoramas installed at the Musee de l’Orangerie in Paris. Click to enlarge and to see many more closeups of Monet paintings.

In 1922, as he was producing his huge, new water lily paintings, he became frustrated by his problems with color, distance, and clarity. He had already destroyed many paintings by the time he saw a physician in Paris and learned he was legally blind in one eye and had only ten percent vision in the other. He needed cataract surgery immediately. Frantic at the idea of a long recovery lying flat on his back, unable to lift his head or move for weeks, Monet had the surgery, but he was an impossible, tempestuous, sometimes violent patient who refused to follow directions. Eventually, he would have three surgeries, refusing to have a much-needed fourth. Emotionally alone, he became convinced that he could not produce the required panels and that his life’s work had no value. Nevertheless, he kept working on these paintings, though he could not bear to part with them or consider them finished. They did not leave Giverny to be installed at the Musee de l’Orangerie until after his death at age eighty-six in 1926, and Monet would never fully comprehend how much his work influenced young artists and taught them how to see. A comprehensive, involving, carefully researched, and well illustrated study of Claude Monet at the end of his life.

Also by Ross King: MICHELANGELO AND THE POPE’S CEILING, BRUNELLESCHI’S DOME: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture, LEONARDO AND THE LAST SUPPER

A short film entitled “Ceux de Chez Nous,” made by Monet’s friend Sacha Guitry in 1915, shows Monet talking with Guitry and (at the one-minute mark) a scene in Monet’s garden with Monet himself painting there:

Photos, in order: Author Ross King is shown at his award ceremony for the Governor General’s Award of Canada for Leonardo and the Last Supper (2012): http://www.ctvnews.ca/

The photo of Claude Monet, Georges Clemenceau, and the Water Lilies may be found on http://www.mamylou.fr/

Edouard Manet made a portrait of his friend Claude Monet and Camille, his wife, in 1874, in Monet’s boat-studio: http://www.manet.org/

One of Monet’s “upside down” paintings with the sky at the bottom as a reflection. This also shows the weeping willows, upside down. Many more Monet pictures shown here: http://poulwebb.blogspot.com/

Three large panoramas are shown from the Musee de L’Orangerie in Paris. To get an idea of scale, these doorways are enormous, and the seating in the center will hold eight people. Many more Monet photos are seen here. http://poulwebb.blogspot.com/

ARC: Bloomsbury