“Despite the heady smell of the hay, the dust makes him cough, dust from the earth they cannot help but harvest along with the grasses, because here whatever you do, there is always dust – beneath the horses’ hooves, behind the carts, on the cows’ rumps….In daytime in the sun it makes him and the others itch so badly they could scratch their flesh to shreds and clamber into the watering trough to calm the irritation, although they know that the moment their skin dries it will itch all the worse.”

Set in Patagonia, in the southernmost part of Argentina and Chile, during an unspecified time period, this novel by French author Sandrine Collette shows life at the edges, as a dysfunctional family tries to stay alive through the herding of cattle and sheep on a remote ranch in the steppe. It is a difficult life made even more difficult by the poor decisions of the adult parents of four boys, each of whom must perform exhausting physical labor required by the parents to survive. Shortly after the novel begins, the father disappears, their mother saying that he “took off” without explanation. After that, the mother assumes the role of boss – and she is one of the most demanding bosses imaginable, performing the kitchen duties and managing the finances while assigning the hard work out on the steppe to her four sons. The novel’s main character, Rafael, is the youngest, at age twelve, when the main action begins, with brother Steban, referred to as a “halfwit,” four years older, and silent. The two oldest boys, twins, are eighteen, and they virtually run the show, their mother giving them free rein to manage their younger brothers regarding their duties and behavior. Mauro, the most muscular twin, is vicious, a true sadist, and, sometimes in combination with his twin Joachim, he bullies the two younger boys, often brutally – beating, punching, and deliberately hurting them with the tacit approval of their mother. The twins believe that young Rafael is to blame for their father’s disappearance.

Set in Patagonia, in the southernmost part of Argentina and Chile, during an unspecified time period, this novel by French author Sandrine Collette shows life at the edges, as a dysfunctional family tries to stay alive through the herding of cattle and sheep on a remote ranch in the steppe. It is a difficult life made even more difficult by the poor decisions of the adult parents of four boys, each of whom must perform exhausting physical labor required by the parents to survive. Shortly after the novel begins, the father disappears, their mother saying that he “took off” without explanation. After that, the mother assumes the role of boss – and she is one of the most demanding bosses imaginable, performing the kitchen duties and managing the finances while assigning the hard work out on the steppe to her four sons. The novel’s main character, Rafael, is the youngest, at age twelve, when the main action begins, with brother Steban, referred to as a “halfwit,” four years older, and silent. The two oldest boys, twins, are eighteen, and they virtually run the show, their mother giving them free rein to manage their younger brothers regarding their duties and behavior. Mauro, the most muscular twin, is vicious, a true sadist, and, sometimes in combination with his twin Joachim, he bullies the two younger boys, often brutally – beating, punching, and deliberately hurting them with the tacit approval of their mother. The twins believe that young Rafael is to blame for their father’s disappearance.

The grim novel which follows is a difficult read, with the boys experiencing no joyfulness, no satisfaction with their work, no love, and no let-up in sight throughout the book. When the mother becomes an alcoholic, as was her husband, and often disappears to gamble at the bar in the remote town nearest their ranch, the boys are left on their own, with unstable Mauro in charge, a situation obviously headed for disaster. When the mother runs into debt from gambling, their fraught lives become even more horrific. She has no financial resources to pay back her debts and no money for supplies for the farm. Before long, she is forced to rely on only three brothers. And when young Rafael accidentally leaves a gate open and two valuable horses escape, he is sent out on his own horse, without supplies, to find them, or else. He is gone for several weeks. Now the mother has only two people left at the farm to do the entire job of shearing hundreds of sheep during the narrow window in which it must be done.

The grim novel which follows is a difficult read, with the boys experiencing no joyfulness, no satisfaction with their work, no love, and no let-up in sight throughout the book. When the mother becomes an alcoholic, as was her husband, and often disappears to gamble at the bar in the remote town nearest their ranch, the boys are left on their own, with unstable Mauro in charge, a situation obviously headed for disaster. When the mother runs into debt from gambling, their fraught lives become even more horrific. She has no financial resources to pay back her debts and no money for supplies for the farm. Before long, she is forced to rely on only three brothers. And when young Rafael accidentally leaves a gate open and two valuable horses escape, he is sent out on his own horse, without supplies, to find them, or else. He is gone for several weeks. Now the mother has only two people left at the farm to do the entire job of shearing hundreds of sheep during the narrow window in which it must be done.

The author alternates points of view throughout the novel, and it is especially revealing in the beginning sections, as this offers the opportunity for the reader to become familiar with the thinking of each main character in their separate chapters, and to see the dangers they face from each other. Here Rafael becomes the main character, with his chapters occurring after each of the others at first, helping to establish his relationships with them. At the same time, it gives the other characters a chance to provide special information of their own to the reader, but not necessarily to the other characters. Early on, for example, the reader learns why Steban, the “halfwit,” has stopped talking, though none of the others know. The Mother, too, has her own chapters, and she earns no sympathy from the reader, confirming what most readers would assume from the outset. “She hates them all the time, all of them…Sometimes she reckons she should have drowned them at birth, the way you do with kittens you don’t want.” It is not until Rafael is sent out to look for the missing horses that he has his first chance to explore the remote areas into which the horses’ tracks lead, places he has never gone before. There, he discovers, for the first time, the woods that lie beyond the steppe where they all live and work – and there, he experiences a strange kind of epiphany, overwhelmed by their beauty.

Full of action, the novel will appeal especially to those who enjoy seeing life lived on the edge, with violence always just a step away, though it sometimes intrudes unexpectedly here and complicates the characters’ lives. In fact, life and death resemble each other so much here that it is difficult, sometimes, not to become weary of the dark mood and the constant disasters. Human life is, as Thomas Hobbes once said, “nasty, brutish, and short,” especially so in this novel, in which there are few changes of tone and no humor to put life into a broader perspective. Life is tenuous at best, and even murder is regarded as a fact of life, one which has no consequences in the limited “society” which is shown here. This macho world provides little to leaven the testosterone-fueled behavior, a limitation which many female readers will understand but find impossible to sympathize with in the present day.

When Rafael was out looking for the missing horses, his brothers rounded up hundreds of sheep, which needed to be sheared before it was too late in the season.

The conclusion will keep book clubs busy with discussion of the big issues. Some will question whether the actions of Rafael as the book ends are realistic, some will suggest that the author needed to end this novel as she did to accomplish the kind of change that a climax requires, some will find it sentimental, while still others may be inspired by Rafael’s actions. The final question is whether Rafael’s actions make sense, considering all he has been through and all that he will face in the future. Will he lead a satisfying life? If so, how? What about Steban? Does he have the knowledge and fortitude necessary for survival? Author Sandrine Collette leaves questions unanswered for her readers, though the outlines of her thoughts are clearly presented.

As the book ends, Rafael finally begins to laugh (for the first time in the book): “Laughter swells inside him and spills over, freeing his throat and his belly, so alive and so bountiful that he shakes the earth, and in the fierce cry he sends out into the world everything begins again and everything is forgotten…what’s done is done, he will have to live with it, and he laughs again, lying with his arms spread wide, singing at the top of his voice. The sun rises on the horizon all at once…and like the sun, he too rises, dusts the dirt from his trousers, gives a stretch and says, “Right.’ ” I wonder how many readers will agree.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://fr.wikipedia.org/

The Patagonian steppe, where Rafael and his family lived, is a huge, flat area, best for the pasturing of sheep. http://www.tierraspatagonicas.com/

The Patagonian forest, on the borders of the steppe, give Rafael a new vision of the world. https://www.tripadvisor.com

When Rafael was out looking for the missing horses, his brothers rounded up hundreds of sheep, which needed to be sheared before it was too late in the season. https://www.alamy.com

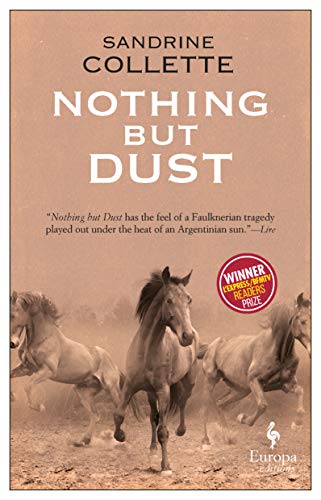

Dust, gauchos, and horses, the atmosphere which Rafael most enjoys. https://www.zicasso.com