“Those who had money and power would never give way. Don’t fool yourselves, lads, this isn’t the Scandinavian bourgeoisie, which agrees to sacrifice its profits in order to survive. The rich here will call in the military, even if the military then swallows them whole….[No,] they’re going to strike and wipe us out…They’re going to crush us, put us in jail, smash us to a pulp, annihilate us.” Comments shared privately by five young men in Uruguay, 1973.

In the years between 1973 and 1981, Uruguay was ruled by the rich and powerful – autocrats who used the power of the military to secure their rule and their continuing wealth – while the needs of the rest of the country were ignored. Idealistic young people and students often talked of challenging this brutal “establishment,” but there was no single leader around to inspire and organize them. As a result, rebellion, if it were to occur at all, would be hit or miss, the private actions of individuals. Journalists often risked their lives to report on news events, student gatherings were monitored, and anyone in the public eye was vulnerable to the whims of those in power. Even the appearance of disloyalty could lead to instant arrest and harsh punishments, including long imprisonments, solitary confinement, immediate exile for a person and his/her family, and even executions – over a dozen a week, on average.

In the years between 1973 and 1981, Uruguay was ruled by the rich and powerful – autocrats who used the power of the military to secure their rule and their continuing wealth – while the needs of the rest of the country were ignored. Idealistic young people and students often talked of challenging this brutal “establishment,” but there was no single leader around to inspire and organize them. As a result, rebellion, if it were to occur at all, would be hit or miss, the private actions of individuals. Journalists often risked their lives to report on news events, student gatherings were monitored, and anyone in the public eye was vulnerable to the whims of those in power. Even the appearance of disloyalty could lead to instant arrest and harsh punishments, including long imprisonments, solitary confinement, immediate exile for a person and his/her family, and even executions – over a dozen a week, on average.

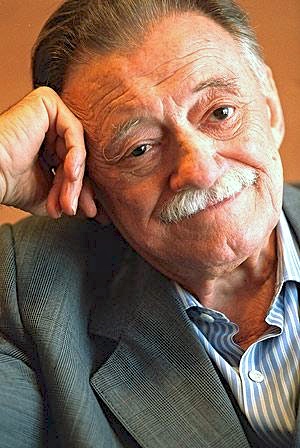

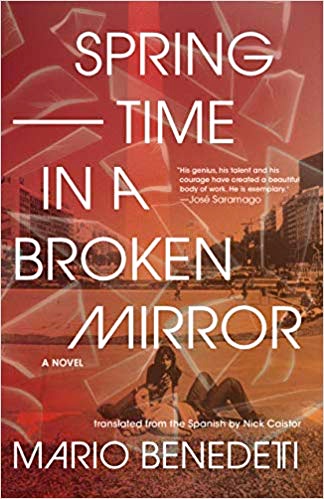

Uruguayan author Mario Orlando Benedetti, widely regarded as one of the most influential writers in South America, was himself arrested and exiled during this time, and he knew many people who were imprisoned, if not executed. Using his firsthand knowledge, he published this extraordinary and revelatory book in 1982, in the days immediately following the end of military rule, giving his audience and the rest of the world a vibrant, literary study of the effects of imprisonment on the hearts, minds, and psyches of people like himself, and of those at home who loved them. Using vignettes featuring various characters in seven different categories of chapters which rotate and repeat throughout the novel, Benedetti begins with The “Intramural” section (“within the walls”), which takes place in prison where an unnamed, sensitive inmate, thinks aloud in separate vignettes as he contemplates his extreme loneliness, his tendency to see phantoms within water stains on his wall, his various memories of his life, including trips to a seaside resort, and the hopes that arise when he thinks of being released. The prisoner feels like an ordinary man – and he undoubtedly is one – one among many who happen to find the government and the military bloodthirsty and merciless and immune to the needs of the general population. Gradually, this character becomes personalized as main character Santiago, a stand-in for the author and all others who came afoul of their rulers.

“Battered and Bruised” introduces Graciela, the wife of Santiago, whose life changes dramatically over the course of her husband’s five-year imprisonment. Working a full-time job as a secretary, she has little free time to spend with their nine-year-old daughter Beatriz, and gradually, as her sections evolve, she begins to feel less “unbalanced, disoriented, and insecure,” and much tougher. Santiago, as shown through his letters, has become, by contrast, much more tender. It is only a matter of time before she is attracted to someone who has been a big supporter for her as she tries to reconcile life and happiness. The “Don Rafael” sections feature Santiago’s father, a former writer living in voluntary exile in a different city, where he dreams of the “kids of today…[becoming] the vanguard of a realistic uprising.” The “Beatriz” sections provide a break in the mood and a child’s point of view, as Beatriz, daughter of Santiago and Graciela, misses her father and especially wants him home so he can take her to the Villa Dolores, a Montevideo zoo, a zoo in which the animals are confined to small cages. (See footnote.). “The Other” sections tell the story of Graciela’s potential lover and the results.

“Exiles,” some of the most personal entries, begin in Montevideo with an unnamed writer receiving a coded warning that the military might be coming his way, leading him and his wife to burn compromising books and newspapers. A succeeding section identifies him as Mario Orlando Benedetti, the author and exile, located then in Lima, Peru, where the police come to him wanting to see his visa. They want him out, obviously on orders from supporters of the junta in Uruguay. He has already had death threats in Argentina, and is willing to go to Cuba, though there is no plane to get him out of Peru in time. In the hour allowed to make his decision, he chooses to go to Buenos Aires. Eventually, in later sections, the impact of the Uruguayan chaos is shown by the Uruguayan exiles he meets who have already moved to Australia, Mexico City, Bulgaria, Germany, and Cuba. At one point, the speaker recalls having met Bolivian President Sales Zuazo in Montevideo twenty years before, when the Bolivian president was himself in exile in Uruguay. There they talked together about Marcel Proust and other literary topics, and met again later on several occasions. Ironically, the speaker sees Saldes Zuazo by accident, in Buenos Aires, and when the speaker confesses aloud that this is his third change of location in his exile, Sales Zuazo admits that he himself is on his fourteenth change. “That night we didn’t talk of Proust,” the author says.

Hernan Siles Zuazo, President of Bolivia, 1956 – 1970, with whom the speaker became friendly during the president’s exile.

Ultimately, the Intramural sections yield to an “Extramural” section after a long journey for the speaker, both real and symbolic. Concluding in 1980, the speaker says, cryptically, that he feels “strange I feel strange walking on this ground/ just as well it’s raining/ the rain makes everything the same and the umbrella becomes humanity’s common denominator/ at least of sheltered humanity,” a particularly poignant ending for this novel about war and peace, not just within one country but within almost a dozen other countries in Central and South America, during the 1960s to 1980s. By concentrating on the human toll of these uprisings in Uruguay, author Benedetti achieves a kind of universality by which American readers can achieve a better understanding of the horrors of the juntas in many other countries, several of which were supported by the United States. The sense of impermanence – and danger – which pervaded the society in which the characters of this insightful novel lived affected everyone who was not part of the military or the ruling class, forcing everyone to concentrate on the present moment, unable to plan for the future. As the speaker of “Extramural” says, after five years in prison, “Springtime is like a mirror but mine has a broken corner/ it was inevitable it wasn’t going to stay intact after this pretty full five years/ but even with a broken corner the mirror is useful/ spring is useful.”

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://profesorbaker.wordpress.com

Villa Dolores, the zoo in Montevideo, featured many small cages with bars containing the animals. In 2015, the zoo responded to complaints by the populace and closed the zoo for four years to reconfigure the cages and make life better for the animals. It reopened in 2019. http://www.uruguaysalvaje.com/zoo-montevideo/

Uruguayans march every year on 20 May in memory of those who went missing under military rule. https://www.bbc.com.

Hernan Siles Zuazo, President of Bolivia, 1956 – 1970, with whom the speaker became friendly during the president’s exile. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/