Note: This novel was WINNER of the Man Asian Prize in 2012. It was also SHORTLISTED for the Man Booker Prize for 2012.

“There is a goddess of Memory, Mnemosyne; but none of Forgetting. Yet there should be, as they are twin sisters, twin powers, and walk on either side of us, disputing for sovereignty over us and who we are, all the way until death.” – Frontispiece, from “A Meander through Memory and Forgetting” by Richard Holmes.

Setting this unusual, aesthetically intriguing, and often exciting novel in Malaya/Malaysia, author Tan Twan Eng* provides insights into the Japanese Occupation of Malaya from 1941 – 1945, while recreating the horrors endured by the local population. At the same time, he also illustrates the highly formal aesthetic principles which underlie Japanese gardens, ukiyo-e (woodblock) prints, and the practice of horimono (literally “carving”), which is part of the long tradition of irezumi, Japanese tattooing. Amazing as it may sound, Tan succeeds in accomplishing an elegant blend of these seemingly incompatible subjects and themes while also appealing to the reader with characters who face personal tragedies and strive, somehow, to endure.

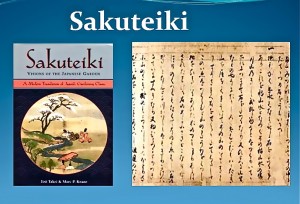

Setting this unusual, aesthetically intriguing, and often exciting novel in Malaya/Malaysia, author Tan Twan Eng* provides insights into the Japanese Occupation of Malaya from 1941 – 1945, while recreating the horrors endured by the local population. At the same time, he also illustrates the highly formal aesthetic principles which underlie Japanese gardens, ukiyo-e (woodblock) prints, and the practice of horimono (literally “carving”), which is part of the long tradition of irezumi, Japanese tattooing. Amazing as it may sound, Tan succeeds in accomplishing an elegant blend of these seemingly incompatible subjects and themes while also appealing to the reader with characters who face personal tragedies and strive, somehow, to endure.When the novel opens, in 1989 or 1990, Judge Teoh has just retired from her work on the Supreme Court in Kuala Lumpur. Only sixty-three, the judge, known familiarly as Yun Ling, has taken early retirement for reasons she does not initially divulge and has returned to the central highlands where she spent many years from her early teens until her late twenties. Though she has not been there for thirty-four years, she is seeking her spiritual home, a garden called Yangiri, which means “Evening Mists.” Nakamura Aritomo, whom she knew many years ago, spent fourteen years developing this special garden according to the principles set forth in Sakuteiki, a book written in the mid- to late eleventh century and which he translated and published in his native Japan. The garden has not been tended for many years, and Aritomo’s nearby house has been empty for the same length of time, but Yun Ling is determined to bring  back Yangiri’s original beauty: first, to honor the memory of Aritomo, whom she originally despised for his connections to Japan, where he was gardener to the Emperor, and second, to honor the memory of her sister, Yun Hong, who did not survive the work camp to which they were both consigned during the Occupation. She knows how hard the restoration work will be – she worked with Aritomo in creating the original masterpiece. She also plans to record all her recollections of the approximately ten years she worked with Aritomo. “I will dance to the music of words,” she says, “one more time.”

back Yangiri’s original beauty: first, to honor the memory of Aritomo, whom she originally despised for his connections to Japan, where he was gardener to the Emperor, and second, to honor the memory of her sister, Yun Hong, who did not survive the work camp to which they were both consigned during the Occupation. She knows how hard the restoration work will be – she worked with Aritomo in creating the original masterpiece. She also plans to record all her recollections of the approximately ten years she worked with Aritomo. “I will dance to the music of words,” she says, “one more time.”

As the novel shifts back and forth chronologically, often quite suddenly, the horrors of the Occupation and the complex political dynamics of Malaya from 1940 – 1945 are revealed. Though the Japanese are the most powerful military force, as evidenced by their Occupation in 1941, they and the local population are also being challenged by the Chinese Communists, led by Mao; the Kuomintang, led by Chiang Kai-Shek; the homegrown Malay Communists; and an aboriginal culture, the Orang Asli, who resent the intrusions into the jungle and forests which they consider their home. Tan describes these groups and their sudden attacks on civilians, while also focu sing on the Japanese labor camp where Yun Ling and Yun Hong are imprisoned, and on the tortures visited upon the detainees, especially the women. Yun Ling is the only survivor of her camp, but how she survived remains a mystery for much of the novel. Other mysteries also keep the interest high. Questions arise as to whether Aritomo may have been involved in a group called “The Golden Lily,” which stole treasures from Japanese-occupied countries and sent them to the Philippines, on behalf of the Emperor. Other questions arise about the Boer family of Magnus Pretorius, which owns the Majuba Tea Estate, located beside Yangiri, and whether someone there may have had connections with the Communists during the war.

sing on the Japanese labor camp where Yun Ling and Yun Hong are imprisoned, and on the tortures visited upon the detainees, especially the women. Yun Ling is the only survivor of her camp, but how she survived remains a mystery for much of the novel. Other mysteries also keep the interest high. Questions arise as to whether Aritomo may have been involved in a group called “The Golden Lily,” which stole treasures from Japanese-occupied countries and sent them to the Philippines, on behalf of the Emperor. Other questions arise about the Boer family of Magnus Pretorius, which owns the Majuba Tea Estate, located beside Yangiri, and whether someone there may have had connections with the Communists during the war.

While Yun Ling is planning her restoration of Yangiri, she agrees to allow Professor Yoshikawa Tatsuji to come from Japan to inspect and possibly photograph thirty-six, never-before-seen ukiyo-e prints made by Aritomo and bequeathed to her. Aritomo was apparently as skilled at ukiyo-e as he was with garden design, both art forms being governed by balance and harmony, and a sense of proportion and unity, the complete opposite of the warfare he and Yun Ling have both faced. An art form practiced secretly by Aritomo, one which is related to the ukiyo-e prints in its use of a “carving” tool, is that of the traditional Japanese tattoo. Tatsuji has seen only one tattoo by Aritomo, on the back of a friend, but as he is a collector of tattooed skin (!), which he sells and trades, he is anxious to find more examples of Aritomo’s style.

- Garden, Imperial Palace, where Aritomo had been gardener

Through hints and small details mentioned throughout the novel, Tan creates interest in Yun Ling’s history, and the eventual discovery of how she becomes the sole survivor of her work camp in the mountains is one of the most dramatic sections of the novel. The author’s depiction of Aritomo’s character also develops slowly. Yun Ling had originally contacted him at the end of the war because she wanted to create a monument in memory of her sister and had decided to create a garden. Though Aritomo refuses to help her with this project, he does say that he will teach her what he knows so that she herself can create the garden she wants. The relationship they develop in the process of working together is revelatory of their different personalities, and as time passes, of their different ways of dealing with memories as they affect their pasts and futures.

Chrysanthemums, Ukiyo-e print by Hiroshige, one of the masters

The Garden of Evening Mists is an unusually ambitious novel, and its focus on Japanese art forms elevates it beyond the horrors of war. I did find the novel a bit difficult to get into, however. The beginning is slow to develop since the author must introduce a number of characters from three different time frames, all with names that are “foreign” and harder than usual for most English-speakers to remember. In addition, the author seems to be trying a bit too hard, stylistically, in the first fifty or so pages, paying more attention to the old adage of using “lively” verbs and verb forms (more per page here than I have come across in years) than he does to the more important one of “keeping it simple.” Once the author gains traction with his story, however, the overwritten passages disappear, and the novel becomes the elegant story of two unusual people dealing with war and the past and, more importantly, finding solace in art, creativity, and abiding values.

*The order of names of characters in this book follows the pattern used in the characters’ countries, with family name first, followed by personal names.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://goodbooksguide.blogspot.com

Sakuteiki, written between the early 11th century and mid-eleventh century, is probably the oldest text in the world about gardening, from http://adligmary.blogspot.com

The photo of the Imperial Garden, where Aritomo was gardener, is from http://www.npointercos.jp

The ukiyo-e print of chrysanthemums is in a shape which suggests how easily it might have been adapted to a tattoo across the shoulders and upper back. http://www.wikipaintings.org

ARC: Weinstein Books