Note: Tim Winton is four times WINNER of the Miles Franklin Award, Australia’s highest literary prize, and was twice SHORTLISTED for the Man Booker Prize.

“I know they’re only stones. And the moon is only the moon. But they’re not empty things you know. The past is still in them. The force of events long gone, it lingers. These heavenly bodies and earthly forms, what are they but expressions of matters unfinished? Perhaps it’s not childish nonsense to see stones as men walking, to behold the moon and feel a tinge of dread. A stone is a fact, a consequence. And the moon, it marks a man’s days…a reminder every cycle that your moment is waning.” – Fintan MacGillis

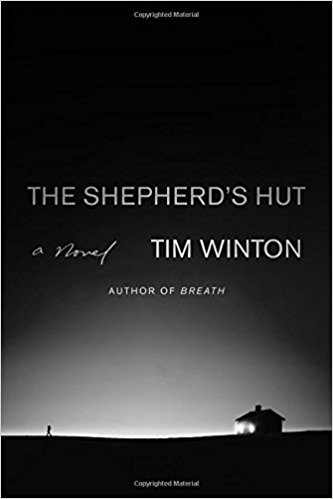

In a novel widely regarded as the high point of his work to date, Australian author Tim Winton expands his view of the world and his ability to create fascinating, even symbolic, characters, placing them in circumstances in which they must take actions for which they may not be prepared. Set in the remote wilds of western Australia, where life is often raw and behavior sometimes lacks the constraints which “civilization,” by definition, requires, Winton creates two characters on their own – a young man, and a former priest living as a hermit, each one abused, and both trying to escape events which have marked them for life. Jaxie Clackton, a seventeen-year-old whose family life has been significant primarily for his beatings, has lived through the lingering death of his mother. His father, a man who seemingly obeys no laws and feels no sense of love for anyone, takes his own frustrations out on Jaxie, beating him mercilessly, sometimes for no apparent reason. Since the family has been totally occupied by their rural life, the butcher shop his father runs, his mother’s illness, and Jaxie’s own tendency to respond to school problems with his fists, Jaxie no longer attends school, and there are no adults who can step in and help him.

In a novel widely regarded as the high point of his work to date, Australian author Tim Winton expands his view of the world and his ability to create fascinating, even symbolic, characters, placing them in circumstances in which they must take actions for which they may not be prepared. Set in the remote wilds of western Australia, where life is often raw and behavior sometimes lacks the constraints which “civilization,” by definition, requires, Winton creates two characters on their own – a young man, and a former priest living as a hermit, each one abused, and both trying to escape events which have marked them for life. Jaxie Clackton, a seventeen-year-old whose family life has been significant primarily for his beatings, has lived through the lingering death of his mother. His father, a man who seemingly obeys no laws and feels no sense of love for anyone, takes his own frustrations out on Jaxie, beating him mercilessly, sometimes for no apparent reason. Since the family has been totally occupied by their rural life, the butcher shop his father runs, his mother’s illness, and Jaxie’s own tendency to respond to school problems with his fists, Jaxie no longer attends school, and there are no adults who can step in and help him.

One day after a particularly terrible beating which has left him with one eye so swollen that he cannot see out of it, Jaxie ponders a future without his father: “I spose it’s wrong to pray that someone dies… But I’ve thought about all the prayers. If that’s what I was doing them years…Asking something, someone, anything, for a big black anvil to fall from the sky like in the cartoons. Kerang! On Wankbag’s head. Because nothing else was gunna save [me]…” And then one afternoon, he gets his wish. He returns home to find his father dead, the victim of an accident while he was working underneath his truck. This is not a religious moment for Jaxie, however. “Praying to get someone killed? Not much philosophy in that.” Instead it is his signal to take off, fearing that someone from the police might think him responsible. Taking only a gun, his phone, and binoculars to help him survive in the wild, he heads north on foot, avoiding cars, trucks, and people, hoping to reach a town three hundred kilometers – almost two hundred miles – away, a place where he had a warm relationship with his female cousin Lee, the only person who has shared loving feelings with him in a long time.

One day after a particularly terrible beating which has left him with one eye so swollen that he cannot see out of it, Jaxie ponders a future without his father: “I spose it’s wrong to pray that someone dies… But I’ve thought about all the prayers. If that’s what I was doing them years…Asking something, someone, anything, for a big black anvil to fall from the sky like in the cartoons. Kerang! On Wankbag’s head. Because nothing else was gunna save [me]…” And then one afternoon, he gets his wish. He returns home to find his father dead, the victim of an accident while he was working underneath his truck. This is not a religious moment for Jaxie, however. “Praying to get someone killed? Not much philosophy in that.” Instead it is his signal to take off, fearing that someone from the police might think him responsible. Taking only a gun, his phone, and binoculars to help him survive in the wild, he heads north on foot, avoiding cars, trucks, and people, hoping to reach a town three hundred kilometers – almost two hundred miles – away, a place where he had a warm relationship with his female cousin Lee, the only person who has shared loving feelings with him in a long time.

Though Jaxie is soon thirsty and out of water, he still keeps his phone with him, as it has pictures of Lee, his cousin on it, but the images on the phone, too, soon run out. Eventually, he finds an abandoned shack with an old water tank, breaks down the door, and gulps water straight from the tap until he can hold no more. As he looks around the cottage, “That’s when I really saw how lucky I’d got. Because along the shelf was a bone-handle butterknife…[and] it had an edge on it. A gun’ll get you meat, no question, but with no knife you can’t hardly get to it.” In the next days he hunts, but he has little success, at one point succeeding in killing a bungarra, a goanna lizard, which he cooks and eats, but he has no way to preserve leftovers. When he eventually kills a “roo,” he strings it up into a tree and continues exploring the area, eventually finding a salt lake which might provide him with a way to preserve his meat. As he walks, he dreams of Lee and, despite his difficult situation, appreciates the sights and sounds of life around him, the vibrant descriptions of which are one of Winton’s trademarks.

Eventually, he sees footprints and wheel tracks, and desperate for more water, he investigates, finding a corrugated iron hut, not much better than the place he had found abandoned, but better built. A goat grazes outside, and inside he hears a man singing. Not able to escape because he needs enough water to get back to his own hut, he hides and observes the old man, who is singing “Wild Colonial Boy,” a song his mother used to sing. Suddenly, the man, who has given no sign that he is aware of being watched, says, quietly, “I’m a civilized fella. I’m not a fool. And I hope you’re no more fool than I. So let’s be civilized fellas together. There’s food here and you’re welcome to it.” Though Jaxie does not trust the man and does not respond, both are aware of each other, and the next morning Jaxie accepts water and food. As the two size each other up, the old man is surprised that Jaxie has found him by accident. His name is Fintan MacGillis, and he is a former priest, now “marooned.” He thinks he has been living in “the shepherd’s hut,” for eight years, being visited only on Easter and Christmas by someone who brings supplies. He does not say why he is there alone.

A euro, one of several mentioned in the book, a marsupial halfway in size between a wallaby and a kangaroo. Photo by John Milbank.

From this point, almost the midpoint, the novel becomes the story of two people, one young, one old, both of whom are trying to come to terms with their lives, the old man reconciled to his place physically, enjoying whatever beauties he can find in nature and the changing light, and the young man wanting, impatiently, to move on. Without changing the persona of either character, author Tim Winton subtly explores the ideas of heaven and hell, guilt and innocence, love and death, and the relationship between man and nature. The former priest used to think the hut “was Hell itself, a place filled with mirages,” a place that he says now serves as “protection for the guilty” instead, and he admits he is not ready to accept the “sacrament of Reconciliation” from the man who brings him supplies. Jaxie has no idea what he is “going on about,” and he stays on alert, fearful that the priest is a pedophile. Fintan says he has seen people pushed into pits with bulldozers, bodies stacked and burnt – and he understands death, even questioning if there is such a thing as a good death, but he does not say where he has seen these things.

As Jaxie becomes more aware of his own place in the world through his connections with Fintan and nature, he also becomes more impatient to see Lee. His desire to leave “the shepherd’s hut” and head north toward Lee and her family precipitates a climax and astounding conclusion which cements, for both men, the views they have developed about life over time. The symbolism is not religious in the traditional sense. Rather, it combines all the themes and ideas of the novel into a grand episode in which each man will have his own epiphany. Perhaps some readers, caught up in the intensity of this story, will join them.

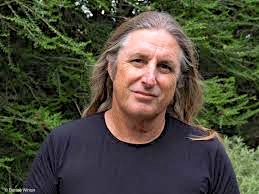

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.penguin.com.au/

The man with the bungarra, a kind of goanna lizard, is seen on http://au.geoview.info Jaxie caught and ate one of these while desperate for food.

A salt lake in western Australia: www.australiangeographic.com.au

A euro, mentioned several times in the book, is actually a marsupial, halfway in size between a wallaby and a kangaroo. http://members.optusnet.com.au/ Photo by John Milbank.

Walking in the outback can be dangerous in areas where there are abandoned gold mines like these. Jaxie steers clear of any area that looks as if people have touched them. http://spiritland.net