“What happens in the Galapagos is determined now by who has more money.”

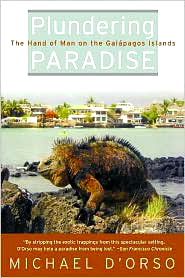

In the “pristine” environment of the Galápagos, unique animals have no fear of man because they have never been exposed to the depredations of man. Ancient tortoises, sea lions, rare birds, and iguanas willingly share their lives with tourists, swim with them, or “pose” for photos. Galapagos life–in the tourist brochures, at least–resembles the Eden found by Charles Darwin in 1831.

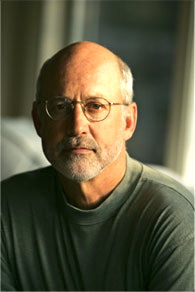

While these images may have been true forty years ago, when small tour boats brought the first tourist-adventurers to the islands, they are far from true now, according to Michael D’Orso, who made a number of visits and spent many weeks on the islands from 1999 – 2002. Located 600 miles from Ecuador, which both claims and governs them, the islands have experienced devastating changes in the past ten years, and some real crises in the past three years. Here D’Orso comments on the crises he’s observed, all of which threaten the very existence of this priceless biological resource and natural laboratory.

While these images may have been true forty years ago, when small tour boats brought the first tourist-adventurers to the islands, they are far from true now, according to Michael D’Orso, who made a number of visits and spent many weeks on the islands from 1999 – 2002. Located 600 miles from Ecuador, which both claims and governs them, the islands have experienced devastating changes in the past ten years, and some real crises in the past three years. Here D’Orso comments on the crises he’s observed, all of which threaten the very existence of this priceless biological resource and natural laboratory.

D’Orso befriends and interviews several astute and eccentric long-time residents of the islands, who serve as first person commentators and give him insight into the islands’ history, explaining how they have changed, and commenting on the ecological disasters now unfolding, to their own horror. Though 97% of the island has been a National Park since 1959, 3% was ceded to the early residents, many of them immigrants from Norway and Germany, who have remained there with their families and lived in tune with the unique  resource which they inhabit. In recent years, however, the handful of families which have lived there for generations have been inundated by 20,000 newer immigrants, mainly economic refugees from the Ecuadorian mainland, all wanting a piece of the tourism pie and not caring what they have to do to get it.

resource which they inhabit. In recent years, however, the handful of families which have lived there for generations have been inundated by 20,000 newer immigrants, mainly economic refugees from the Ecuadorian mainland, all wanting a piece of the tourism pie and not caring what they have to do to get it.

In clear and unambiguous prose, which he sometimes wields like a truncheon, D’Orso excoriates corrupt local officials, judges, and members of the national government who have vested interests in subverting environmental protections because of their financial interests in the oil, fishing, boating, and tourism industries. The government, he says, is “so horrifically convoluted and corrupt that onlookers have taken to calling this country ‘Absurdistan.'”

The introduction of non-native animal species (rats, feral dogs and cats, pigs, goats, and burros), along with foreign insect life (wasps, roaches, and fire ants), and foreign plants (blackberry, lantana, and wild guava bushes) have already permanently changed the environment on which much of the Galapagos wildlife  depends, and some formerly lush areas are now denuded. The wanton flouting of fishing regulations, both by the new immigrants and by the government, and the failure of the authorities to prosecute violators have led to the continued harvesting of sea cucumbers and other marine life, willy-nilly, while fishing boats with long-lines up to 75 miles long continue to hook and kill protected species. Leaky, never inspected oil tankers, sometimes owned by highly placed officials, carry petroleum to the islands, and the first major oil spill has already occurred. Many of these tankers, like the one responsible for the recent leak, carry bunker fuel, almost raw petroleum, which is so heavy that it sinks to the bottom before it can be contained, leaving the oil and the permanent damage from this latest spill underwater, unable to be calculated.

depends, and some formerly lush areas are now denuded. The wanton flouting of fishing regulations, both by the new immigrants and by the government, and the failure of the authorities to prosecute violators have led to the continued harvesting of sea cucumbers and other marine life, willy-nilly, while fishing boats with long-lines up to 75 miles long continue to hook and kill protected species. Leaky, never inspected oil tankers, sometimes owned by highly placed officials, carry petroleum to the islands, and the first major oil spill has already occurred. Many of these tankers, like the one responsible for the recent leak, carry bunker fuel, almost raw petroleum, which is so heavy that it sinks to the bottom before it can be contained, leaving the oil and the permanent damage from this latest spill underwater, unable to be calculated.

Jack Nelson, U.S. Consulate warden, whose family was one of the earliest to settle in the islands, tells D’Orso that it’s not the tourists who are the problem. It’s the people and businesses that “have flocked to the islands in pursuit of the dollars washing off those tour boats [that] are the agents of destruction.” These people have resorted to violence. So determined is the most recent batch of immigrants to undermine environmental control that they have brought in thugs, “lobster mobsters,” to help them gain a freer hand to mine the marine riches of the islands. Recently, these men physically destroyed the National Park and Darwin Station offices, along with the homes of the employees, even ripping out the toilets. The government’s response? Extending the fishing season, as the protesters demanded.

Jack Nelson, U.S. Consulate warden, whose family was one of the earliest to settle in the islands, tells D’Orso that it’s not the tourists who are the problem. It’s the people and businesses that “have flocked to the islands in pursuit of the dollars washing off those tour boats [that] are the agents of destruction.” These people have resorted to violence. So determined is the most recent batch of immigrants to undermine environmental control that they have brought in thugs, “lobster mobsters,” to help them gain a freer hand to mine the marine riches of the islands. Recently, these men physically destroyed the National Park and Darwin Station offices, along with the homes of the employees, even ripping out the toilets. The government’s response? Extending the fishing season, as the protesters demanded.

With the fall-off in tourism as a result of September 11, the economy of the Galapagos is now feeling significant economic effects. The demands to reduce the environmental regulations even further are getting louder, as the “cash cow” of tourism seems to be vanishing, and the current Ecuadorian President seems to be listening to the demands to relax controls even more.

With the fall-off in tourism as a result of September 11, the economy of the Galapagos is now feeling significant economic effects. The demands to reduce the environmental regulations even further are getting louder, as the “cash cow” of tourism seems to be vanishing, and the current Ecuadorian President seems to be listening to the demands to relax controls even more.

D’Orso is passionate in his desire to awaken the world community to the disaster he has seen before the islands have been totally destroyed. His book is timely, and his data seems reliable, though often anecdotal. His forecast is bleak, but his message, and his book, are strong. Those who have dreamed of walking in the footsteps of Charles Darwin in a pristine environment untrammeled by man may find that they have already missed their chance.

Notes: The author’s photo by Genevieve Ross is from http://en.wikipedia.org

A cruise ship with five hundred passengers landed its passengers at the Galapagos in 2007, inspiring Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa to declare the ecosystem now “at risk.” Good article and photo here: http://www.guardian.co.uk

An estimated 15,000 marine iguanas were killed in the oil spill in the Galapagos in 2007. See photo. http://greenrage.wordpress.com

An oil-covered Galapagos sea lion is shown on http://reliableanswers.com