“[Author Gertrude Stein often talked] about how the place where she’d grown up in Oakland had changed so much, that so much development had happened there, that the there there, was gone, there was no there there anymore….This quote is important to Dene. This there there. He hadn’t read Gertrude Stein beyond the quote. But for Native people in this country all over the Americas, it’s been developed over, it’s buried ancestral land, glass and concrete and wire and steel, unreturnable covered memory. There is no there there.”

In this debut novel by Native American author Tommy Orange, the missing “there there” dominates not only the action of the novel but the very souls of its characters. Starting with a powerful and devastating Prologue in which the author tells the history of the contacts between Natives and newcomers from the earliest days of the settlement of the country, Orange begins with the first land deal between Massasoit and settlers in 1621, which ended in a meal of celebration. Two years later, another meal was held between the same settlers and the Natives – and two hundred Natives died of poison. Hangings, a bloody “Indian war” in which the Natives had no guns, the seizure and dismemberment of Massasoit’s son Metacomet, and the burning alive of between four hundred and seven hundred Pequots at their annual Green Corn Dance are the lasting cultural memories the Natives have of the earliest settlers. Later, as the settlements moved west, the bloody mutilations, tortures, and sadistic behavior of the army continued, unabated.

In this debut novel by Native American author Tommy Orange, the missing “there there” dominates not only the action of the novel but the very souls of its characters. Starting with a powerful and devastating Prologue in which the author tells the history of the contacts between Natives and newcomers from the earliest days of the settlement of the country, Orange begins with the first land deal between Massasoit and settlers in 1621, which ended in a meal of celebration. Two years later, another meal was held between the same settlers and the Natives – and two hundred Natives died of poison. Hangings, a bloody “Indian war” in which the Natives had no guns, the seizure and dismemberment of Massasoit’s son Metacomet, and the burning alive of between four hundred and seven hundred Pequots at their annual Green Corn Dance are the lasting cultural memories the Natives have of the earliest settlers. Later, as the settlements moved west, the bloody mutilations, tortures, and sadistic behavior of the army continued, unabated.

Over three centuries later, Orange tells us, “Getting us to cities was supposed to be the final, necessary step in our assimilation, absorption, erasure, the completion of a five-hundred-year-old genocidal campaign. But the city made us new, and we made it ours. We didn’t get lost amid the sprawl of tall buildings, the stream of anonymous masses, the ceaseless din of traffic. We found one another, started up Indian centers, brought out our families…and the cities took us in.” The Urban Indians were born in the city and belong to the city, he emphasizes, people who “know the downtown Oakland skyline better than we did any sacred mountain range, the redwoods in the Oakland hills better than any other deep wild forest…. the smell of gas and freshly wet concrete and burned rubber better than we do the smell of cedar or sage…which isn’t traditional, like reservations are not traditional, but nothing is traditional, everything comes from something that came before, which was once nothing. Everything is new and doomed.”

Over three centuries later, Orange tells us, “Getting us to cities was supposed to be the final, necessary step in our assimilation, absorption, erasure, the completion of a five-hundred-year-old genocidal campaign. But the city made us new, and we made it ours. We didn’t get lost amid the sprawl of tall buildings, the stream of anonymous masses, the ceaseless din of traffic. We found one another, started up Indian centers, brought out our families…and the cities took us in.” The Urban Indians were born in the city and belong to the city, he emphasizes, people who “know the downtown Oakland skyline better than we did any sacred mountain range, the redwoods in the Oakland hills better than any other deep wild forest…. the smell of gas and freshly wet concrete and burned rubber better than we do the smell of cedar or sage…which isn’t traditional, like reservations are not traditional, but nothing is traditional, everything comes from something that came before, which was once nothing. Everything is new and doomed.”

Focusing on the lives of twelve urban Indians at various times in their shared lives from the last half of the twentieth century to the present, Orange shows through these characters’ stories how the present urban culture, combined with active internet usage, has further changed Native life while leaving unchanged some of its most destructive aspects, and few readers will emerge from reading this book without having many serious questions about the future of these urban Indians and the culture which may be evolving. The novel is divided into four sections: Part I, “Remain,” takes a close look at those who Remain tied to the previous culture, at least at this stage of their lives: Tony Loneman is the twenty-one-year-old son of a mother who passed along Fetal Alcohol Syndrome to her son. With his mother now in jail, his father dead, and his caretaker now dying, Tony is alone. Because of his very limited understanding and his naïve willingness to sell “weed,” he is being used by Octavio, a higher up, who wants him to participate in the upcoming Oakland powwow and do some shady errands for him. In a flashback, Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield is twelve when she and her sister Jacquie Red Feather are told by their mother to pack a few things for a move – to Alcatraz, where they become, in early 1970, part of a group of Native Americans who occupy the abandoned prison until June, 1971. Back in the present, Edwin Black, with a Master’s degree in Comparative Literature, is addicted to the internet, which he searches for information about his unknown father, whose name is Harvey and who once lived in Phoenix. Edwin’s current job is working for the Indian Center organizing the upcoming powwow.

Part II, “Reclaim,” begins with another new character, Bill Davis, who loves Karen, the mother of Edwin Black. Bill is often on drugs, served five years in San Quentin, but changed his life. Calvin Johnson, also new, is in debt to Octavio, the drug supplier influencing Tony Loneman. Calvin, who was robbed before he got to the powpow, will now have to work for Octavio to pay off his debt. Jacquie Red Feather, sister of Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield, has a family story of children, losses, and hard luck which few will forget. Part III, “Return,” shows some of these characters and some new ones as they try to return to some of the old values. The most active characters in this regard are the women, some of them, like Opal, caring for nephews, grandsons, or cousins and trying to protect them.

Native dancer, at Powwow, the way Orvil Red Feather imagines himself.

All these characters and others come together in the final section, “Powwow,” which emphasizes their various relationships, some of them quite innocent, as a dramatic and powerful ending unfolds. The author prepares the reader for the speed of the developing action by reducing the individual vignettes from a single page or two, to some only half a page long by the time the final action starts, counting on the reader to make connections among them. Many readers will be shocked by the final pages, and many will think, I’m sure, that the ending came too fast and without enough warning. Others, however, will read this action from the point of view that the author prepared the reader for over the course of the entire book. The messy lives of all the characters, their alienation from the past and lack of a firmly held culture, and their tendency to live in the moment, a characteristic obvious from the amount of escaping they do via alcohol and drugs, shows that life is not pretty here. As the author has said in the Prologue, “Everything is new and doomed,” a sad ending which may only be salvaged by the actions of the women who are there to pick up the pieces as they try, ultimately, to create a there there.

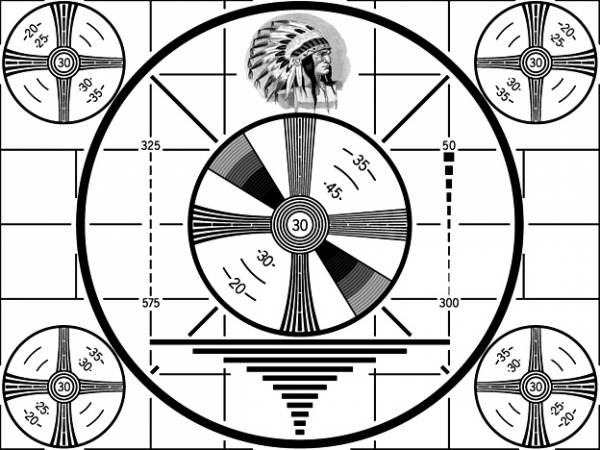

The novel has several references to the Indian head test pattern used for black and white TV up to 1970.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://www.independent.co.uk

The Teepee on Alcatraz featuring John Trudell, is an AP photo from https://mashable.com/

The black and white photo of the demonstration on Alcatraz is may be found on https://mashable.com

The powwow dancer, as Orvil Red Feather imagines himself at the powwow, is from https://theblondecoyote.files.wordpress.com

The novel contains several references to the Indian head test pattern which appeared on TVs carrying black and white programming, up to 1970. https://en.wikipedia.org/